|

By: Matthew Buns, PH.D. Originally Published in: Techniques Magazine Provided by: USTFCCCA As the twig is bent, so grows the tree. - Alexander Pope

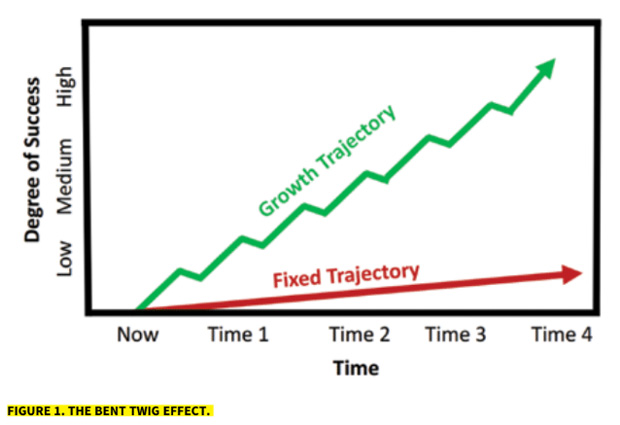

It has been said that the journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. This concept underscores the idea that successful seasons can have very small beginnings. High-performing coaches and athletes do not despise the small beginnings but actually show great joy to see the work begin. After all, small beginnings can bring down mighty mountains (Zechariah 4:10). The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines trajectory as "the path followed by a projectile flying or an object moving under the action of given forces." Put simply, trajectory refers to the path in life that an individual chooses. The ability to learn a wide variety of new motor skills through-out life is one of the most essential capacities possessed by humans (Edwards, 2011). Understanding how track & field athletes acquire skills, and how they can demonstrate expertise effectively, is a particularly critical and useful area of coaching knowledge. Many of the same fundamental principles of improvement apply to a track athlete competing in his first race and a field athlete learning to throw the javelin. The purpose of this article is to briefly describe highly-predictable principles that describe the process underlying performance improvement within the context of track & field skill development. THE BENT TWIG EFFECT The Bent Twig Effect illustrates the relationship between path and outcome and is centered on the idea that early influences have a permanent effect (Sigelman, 2012). If you push a small twig slightly away from its normal pattern of growth, you can cause a major change in the ultimate location of the branch that grows from that twig. Pushing on a branch that is already developed has much less effect. The Bent Twig Effect is also evident in track & field. When athletes continue to progress in a certain direction, they are more likely to reach a desired end goal. However, a slight change in trajectory can lead to significant differences in the outcomes achieved. The path an athlete chooses will have a significant impact on the outcomes they desire in life and sport. In her book "Mindset: The New Psychology of Success," Carol Dweck (2008) famously described two basic mindsets that are believed to significantly shape a person's path toward success or failure. The fixed mindset assumes that intelligence and ability is static, meaning it cannot change in a meaningful way. A growth mindset, on the other hand, strives for challenge and recognizes failure not as evidence of incompetence but as a springboard for growth. In a similar manner, an individual with a fixed trajectory moves toward an unrewarding path that will not take them to achieving desired outcomes (Figure 1). One of the most glaring characteristics of an athlete following a fixed trajectory is a lack of persistence; the athlete might appear to pursue success diligently until success no longer comes easy to them. At this point, they fail to demonstrate a high level of self-motivation and lack confidence in the face of setbacks. In the presence of repeated failure, the athlete with a fixed trajectory lacks mental focus and appears to give up easily. The longer a person

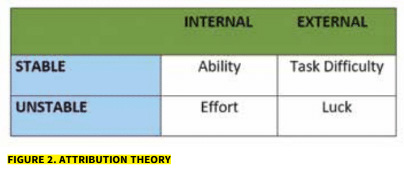

As coaches and athletes alike have noticed, the trajectory toward success is not always linear. Even if goals are set with a growth mindset, that does not mean athletes will progress in a forward pattern from start to finish. There may be unexpected setbacks or times where progress stalls. This is normal, and the athlete who recognizes this holds the advantage. Positive and informed athletes look for a possible solution to challenges rather tha One of the most important decisions an athlete can make is to determine the correct trajectory. The more time an athlete stays on the growth trajectory, the closer they get to achieving desired outcomes. High performers are often motivated by the goal of improvement rather than enjoyment. The earlier an athlete makes the decision to follow a growth trajectory, and the earlier they actually take action, the greater the degree of success at achieving desired outcomes. Effective coaches will create opportunities for athletes to examine their current trajectory and reflect on whether continuing on this path will lead to the most desired outcomes. ATTRIBUTION THEORY According to Attribution Theory, for any test of skill or competence, there are four possible explanations for the outcome, regardless of success or failure (Thomas, Lee, & Thomas, 2008). These attributions (Figure 2) have two dimensions: locus of control (internal or external) and level of stability (stable or unstable). The preferred attribution is effort, because effort is related to practice. Furthermore, effort is under an athlete's control and is variable (can change). The law of practice is one of the most highly reliable laws in learning theory. Performance improvement continues as long as practice continues, but the rate at which it occurs gradually and predictably diminishes over time (Evans, Brown, Mewhort, & Heathcote, 2018). Thus, the object is to have an athlete give maximum effort all of the time. Expecting to improve without any effort is like waiting for a ship at the airport. Task difficulty is the coach's responsibility. Coaches should provide practice tasks that are challenging but feasible. Whenever possible, athletes should have a 50-50 chance of "success" when they give maximum effort. Tasks that are too easy can be boring and do not help athlete's master new skills. Tasks that are too difficult do not help them learn and may be overly frustrating. The lawful pattern of improvement shows regularity for virtually all track & field skills (although the exact rate will change depending on the skill and learner). Ability is often viewed as talent. Talent is often not a powerful predictor of performance in many track and field events. However, talent is often presented as a major factor by athletes (particularly those with a fixed mindset). If talent was the most important factor in performance, practice and coaching in general become unimportant. The ability to do a task changes slowly with practice, which is why it is viewed as stable. Ability does not change from moment to moment. When acquiring new track & field skills, most athletes experience their greatest rate of improvement early in process, whereas once the skill has been learned to some moderate level of performance, further improvement becomes increasingly difficult. Luck is often used as an explanation for outcomes. For example, athletes with a fixed mindset often say luck explains victory. Athletes on winning teams usually expect a win, even after a loss. Athletes on losing teams tend to predict a loss, even after a win. Luck is both external and unstable and, therefore, a poor choice. The assumption with attribution theory is that athletes learn attributions, and the most appropriate attribution is effort.

BEGIN WITH THE END IN MIND Start each season with the end in mind. The world is full of people who can start a task, but it is the finishers in track & field who are a premium. Outstanding coaches do not only emphasize the end goal or outcome - they also encourage athletes to "find their mark," an intermediate goal or objective. When athletes focus on a short-term objective and move toward it, they are more likely to stay on a growth trajectory. If you know anything about bowling, you know that each lane has on it a series of marks that lie just a few feet in front of the bowler. Good bowlers use these marks to aim their bowling balls so they ultimately strike the pins in the proper place. Ironically, the expert bowler doesn't aim at the pins; she focuses on the mark. If you only aim for the pins, you won't hit your ultimate goals. Encourage athletes to head toward that mark, and their ultimate goals will come into view. To summarize, the decisions an athlete (or a coach for that matter) makes during the initial days or weeks of practice shape the trajectory of their season, and ultimately the trajectory of a career. Thus, it is important for athletes to develop good habits early in the season. Here is some basic advice to help athletes begin the season on a growth trajectory with the end in mind: Identify desired outcomes in life and in track & field or cross country. Determine whether the current trajectory or path is leading to those outcomes. If not, identify what actions and steps are required to progress down a growth trajectory. Make an immediate decision, take immediate action, and take the first step on a new growth trajectory. Stay focused, determined, and disciplined in moving down the path of a growth trajectory. This may be the most difficult challenge to face. It's human nature to want to stick to things we know and are comfortable with. Athletes should examine their own comfort zone and remain committed to expanding that comfort zone to reach desired outcomes. Success in athletics requires a great deal of effort, preparation, and feedback. Many athletes and coaches want to be great until they learn what is required to be great. Following the 2016 Summer Olympic Games, swimming legend Michael Phelps, when asked about the key to his success, stated, "In order to get to where you want to go, you need to be willing to do the things that other people aren't willing to do." More individuals would probably train harder if they knew, or only had some type of sign, that the hard work would pay off. However, you do not always know what the outcome of your hard work will be. Let obedience lead to the next step, and encourage athletes to go out on a limb because that is where the fruit is! After all, the tallest oak tree in the forest was once a little nut that simply held its ground. Athletes interested in growth and development are able to start their own engine and arrive to practice with their motor running and ready to be their best. This means that athletes must expend considerable effort and demonstrate mastery - sometimes at a level previously unexplored. There is no textbook for this type of work. However, the rewards for success are great. REFERENCES Dweck, Carol S. (2008). Mindset: the new psychology of success. New York: Ballantine Books. Edwards, W.H. (2011). Motor learning and control: From theory to practice. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. Evans, N.J, Brown, S.D., Mewhort, D.J.K., & Heathcote, A. (2018). Refining the law of practice. Psychological Review, 125(4), 592-602. Sigelman, Carol K & Rider, Elizabeth A & Sigelman, Carol K. Life-span human development. 7th ed (2012). Study guide: Life-span human development (7ed). Wadsworth, Cengage Learning, Belmont, California. Thomas, K.T., Lee, A.M., & Thomas, J.R. (2008). Physical education methods for elementary teachers. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Matthew Buns, PH.D., is an Assistant Cross Country and Track & Field Coach and Associate Professor of Kinesiology at Concordia University, St. Paul. While competing at Concordia University, Nebraska, he was a two-time NAIA All-American and two-time Academic All-American. During his coaching tenure, Buns has helped coach 19 NAIA All-Americans in Track & Field and two NAIA All-Americans in Cross Country. |

remains on a fixed trajectory, the less likely they are to ever achieve desired outcomes because the degree of difficulty is much greater with each time segment that passes. Those who are able to master skills in track & field follow a growth trajectory and recognize that improvement and the path to success isn't always fun. Fortunately, making only the slightest alterations to a trajectory can have a profound effect on a person's achievement. When an athlete decides to follow a growth trajectory, progress will eventually follow, even though initial progress may be small. In the presence of failure and seeming futility, expert performers carry on confident that they will figure it out.

remains on a fixed trajectory, the less likely they are to ever achieve desired outcomes because the degree of difficulty is much greater with each time segment that passes. Those who are able to master skills in track & field follow a growth trajectory and recognize that improvement and the path to success isn't always fun. Fortunately, making only the slightest alterations to a trajectory can have a profound effect on a person's achievement. When an athlete decides to follow a growth trajectory, progress will eventually follow, even though initial progress may be small. In the presence of failure and seeming futility, expert performers carry on confident that they will figure it out. n succumbing to frustration. Researchers have identified a link between positivity and the ability to perform. Positive emotion builds resourcefulness in ways that help athletes become more resilient to adversity and perform at a higher level. It has been said that a bad attitude is like a flat tire - you can't go anywhere with it! The goal is to achieve overall forward movement toward a goal without ignoring the huge efforts and setbacks that are required to make success possible. As aforementioned, success can be "messy" and is not always achieved on the first attempt or without setbacks. However, the athlete following a growth trajectory proceeds with outstanding effort and work-like intensity even though it may generate no immediate rewards.

n succumbing to frustration. Researchers have identified a link between positivity and the ability to perform. Positive emotion builds resourcefulness in ways that help athletes become more resilient to adversity and perform at a higher level. It has been said that a bad attitude is like a flat tire - you can't go anywhere with it! The goal is to achieve overall forward movement toward a goal without ignoring the huge efforts and setbacks that are required to make success possible. As aforementioned, success can be "messy" and is not always achieved on the first attempt or without setbacks. However, the athlete following a growth trajectory proceeds with outstanding effort and work-like intensity even though it may generate no immediate rewards.