|

By: Cord Sgaglio Originally Published in: Techniques Magazine Provided by: USTFCCCA This article is meant to help new and developing coaches understand the basic concept of periodization and progression of training. We will also look at key components that can influence training and progression from a big picture point of view. The information that will be discussed is nothing new as far as concepts are concerned, they have existed for decades. These concepts have remained relevant for this amount of time because of their importance in the facilitating high performance training. In better understanding of these basic concepts, you will be able to create a more progressive and productive training system.

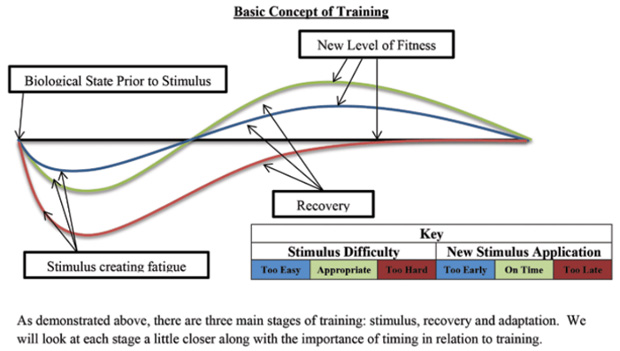

Periodization for the purpose of this article can be defined as a systematic approach to the progress of training. My goal is to help educate and motivate coaches to become better and think more critically. The ultimate object here is to quantify a few common errors in periodization and help offer ideas and concepts that can be used to help prevent some of these issues and improve training overall. Let's begin with the basic concept of training. The model below is based on General Adaptation Syndrome or (GAS) which was originally developed in 1936 by Hans Selye. This premise states all athletes begin at a certain biological state. Once a stimulus is applied, fatigue will set in. When the individual recovers, they do so to a new level of fitness if allowed. This is the basics of all training. What makes this difficult is ensuring we are applying the correct stimuli and the introduction of outside variables. These variables can come in many forms, which we will discuss later in the article. However, it is because of this that I recommend controlling or being aware of as many of these variables as possible. This will allow you to make better, more educated decisions in training.

STAGES: STIMULUS This begins the cycle. Stimulus comes in many forms, it does not solely stem from training. The human body cannot differentiate between stressors, or stimuli. This means that anything that takes the body out of homeostasis, whether psychological or physiological, will cause fatigue to some degree. This fatigue will come at the tissue level, rather than the organ or system level. It is imperative that we as coaches recognize this and address it by taking inventory of our athlete's daily life accounts. This will allow us to limit possible variables that can influence training and training results. Consider asking your athletes how they are doing prior to a workout or run. If they seem distressed, it would be advantageous to reduce the volume or intensity of the days training. If not properly identified and adjusted for, these external stressors paired with the training can cause undesired training and performance outcomes. The second portion of stimulus is application time. As shown above, applied to early or too late we will not gain the desired training outcome. RECOVERY Possibly the most over looked and under-appreciated portion of training, recovery is the time in which the athlete adapts to the stimuli. There are many variables to this, such as the individual athlete's inherent ability to recover. These next few variables are very well known, but because of their level of importance, they must be noted. The nutrition of the athletes, and when and how much they are consuming. Ideally the window of nutrition post work-out is 30 to 90 minutes. The further away, the less gains will occur. It is also ideal

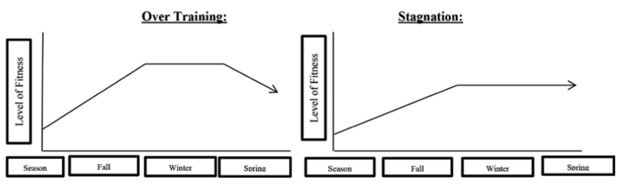

ADAPTION During this section, we see the true results of the training. At this point the athlete has adapted to the training stimuli we implemented. There is no definitive time line for this. The best way to quantify this is to know your athletes. One rule developed by Bill Bowerman was the Hard-Easy approach. This approach pairs a hard day of training with an easy day following it for recovery. In essence this may work, but again with external stimuli and different athletes you must be tailoring the training accordingly. TIMING Timing must also be taken into account. When the stimuli is applied; applying a new stimulus too early or too late will result in less than ideal effects on training. The proper time to apply a new stimulus will depend on several variables. A few of those variables include: the individual athlete and their adaptability, the prior training stimulus and its potency, and finally any external stressor that may reduce the ability to recover. Communication and proper notation of athlete's progress can be vital in implementing proper timing of new workouts and training. Now that we have identified the basic principle of training and the major components, let's think periodization! The simplest way to think of this is a continuum of improvement as the year(s) develop. There are many types of periodization and ways to approach it. This article is not geared toward a specific one, and rather the proper progression of training in general. The goal should be to gain fitness as the year(s) develops. Unfortunately periodization does not always happen that way, and what we are left seeing is more like the diagrams above. OVER TRAINING Let's take a look at both of these figures and identify how they progress. Tracing our Over Training graph, we see an incline in fitness during the Fall season followed by our highest level of fitness during the Winter season and eventual decline in Spring. To clarify, this is just a simple model: the peak level of fitness and decline may occur at any point in the year, and these seasons were chosen for convenience. The main cause of this Graph is over training. Reading the graph we see a preliminary ability to handle the work load applied and improvement occurs. However, without proper recovery the athlete eventually stagnates and finally ends with a decrease in fitness due to their inability to recover. This would be closely related to over training syndrome, when the athlete is training at too high of a level without the ability or opportunity to recover. Consider what we just discussed in the previous portion as it pertains to stimulus, recovery and adaptation and how they are the building blocks of periodization. The Stagnation graph portrays a slightly different story. Again, we see an increase in fitness during Fall and a plateau to stagnation during the Winter. The main difference between the Stagnation graph and the Over Training graph is the decline in fitness does not occur. Instead, as the title indicates, we see stagnation and no further improvements in fitness. The main cause of stagnation is the lack of new stimulus in training. This will create a reduction in adaptation, eventually resulting in stagnation. There are many other examples of improper periodization resulting in poor performances, but these two models are the most common. I am certain that you can think of at least one team that has had one of these two unfortunate outcomes. It may even be your own. Remember, we must first identify an issue before we can begin to solve it. With that in mind, the next section of this article is geared toward some fundamental rules that can help solve and prevent these periodization malfunctions from happening. FUNDAMENTAL RULES OF TRAINING RULE OF DIMINISHING RETURN In order to continue to develop and gain fitness you must increase/vary the stimulus. If you continue to use the same stimulus all year without any modifications, the body will no longer adapt and fitness will eventually decline. This we saw in primarily in the Stagnation graph. By allowing for variety in your program, you will create not only new/different stimuli physically but also keep athletes engaged mentally as well. Just remember to make sure everything you are doing is for a specific purpose. Adding variety at the cost of function is never acceptable! Nor will it create desired results. EXAMPLE If you take a non-runner and have them run one mile a day for a week, they will become sore. If you have that same non-runner continue to run one mile a week for several weeks the soreness will dissipate and the run will become effortless. It is as the body adapts to the stimulus we begin to see a reduction in gains, eventually if the stimuli does not change, there will no longer be any gain in fitness. During this time we must implement a new stimulus. The most basic forms of this are volume (increase the distance) intensity (Run faster) and rest (reduce the break in-between reps or sets). Through the manipulation of one of these three stimuli, we create a new need for adaptation. Ensure you know which variable you are manipulating. Also, focus on manipulating one at a time or it will be difficult to quantify which manipulation is producing what result. RULE OF RECOVERY As demonstrated in the GAS model, the function of recovery is vital to obtaining a new level RULE OF INDIVIDUALIZATION Every athlete responds to training differently. With this in mind you must train each athlete as the individuals they are. Focus on the demands of the events to begin, but never lose sight of the individuals you are coaching. Identify your athlete's strengths and build off them, know if they are a runner or a pusher for the 100m or if they rely on speed reserve or strength for the 800m, these are just a few examples of subtle differences that make a huge impact on training. One size does not fit all, and cookie cutter systems only work so well on some athletes. The prestige of a Coach should be based on their coaching window. This refers to the spectrum of athletes a Coach can cultivate performances from. This spectrum ranges from one trick ponies who rely on talent to get results to Coaches that are capable of producing performance from any athlete willing to put in the work. THEORY OF ALLOCATION PRINCIPLE This starts with the five main motor performance abilities which are: endurance, strength, speed, coordination and flexibility. The allocation principle states that when increasing one of these five motor performance abilities we lose out on the potential for another. Putting it simply, you cannot train successfully to be a world class sprinter and marathon runner at the same time. With this in mind, it is crucial to consider the demands of the event and train accordingly. TRAIN CONSISTENTLY Surprisingly, this concept is not always considered during the planning phase. Remember it is in consistency that we find true adaption and progression in training. Without a consistent regiment of training, it can be very difficult to determine what is and what is not working in training. Also, without consistency, we lose a lot of benefits that come from the accumulation of training. Some adaptations take months and even years of constant training to achieve. It is only with quality consistent training we can perform at the highest level. It is important to ensure breaks and transitions between seasons as they are significant for recovery both mentally and physically. The big concern is their duration. These breaks and transitions should not cause an abundance of fitness loss. HAVE A MASTER PLAN Think of training as a road trip, the destination being your big competition. Once you have your destination, you can begin to chart a course, working backwards from your big competition to the start of the season. This is meant to serves as an outline, not a definitive route. Along the way you will need to make changes, just like any road trip. Be flexible, be adaptive, and you will make it. HAVE A CONTINGENCY PLAN, HAVE TWO Always have a contingency plan. The science may indicate that your athletes have recovered from a training session or prepared for a specific workout, but once warm up starts or after a few reps, the results or their form may tell a different story. Coach what you see - after all, it is about individual athletes, not reps or sets. Another consideration for your training is the weather, it will not always cooperate with your plans so be prepared to make changes. Bottom line: be adaptable. Do not be adapt and, like the dinosaurs, you will perish.

GOOD NOTES This final rule may seem off base from the others but it truly is vital. Having detailed notes is fundamental for writing and tracking training. These notes will help create a baseline, giving you something to build off and reflect on. This is imperative to see if the training is working or not. If athletes are progressing properly, the results in workouts should reflect this. Remember, without proper notation and record keeping, it can be very difficult to know what is and what is not working for each athlete. CONCLUSION Understanding of the basic concepts of training along with the utilizing these fundamental rules is a sure fire way to facilitate successful training. It is generally when we step too far from the basics that we lose sight of our ultimate goal, which is improvement. As you begin to plan training for the next season, or for your current season, consider these rules and lessons. Remember progression, not regression. It is easier to reverse a mistake early, but we must identify it as that! Finally, keep learning and asking questions! Cord Sgaglio is the Head Men's & Women's Cross Country Coach and Assistant Men's & Women's Track & Field Coach at Limestone College. Photo Credit: Kirby Lee |

of fitness. Another main reason we see athletes do well in the fall and begin to stagnate and finally decline by the spring is the lack of recovery. This rule can affect both graphs, but primarily we see the rule of recovery in the Over Training Graph. Without proper rest in-between bouts of training, all athletes will eventually break down, and fitness goes from stagnation to decline. One reason they have success in the fall and part of winter is over training has not yet fully set in. The three main outcomes of overtraining are injury, illness and decline in performance. There are a few potential warning signs that over training is setting in. One of them is a higher resting heart rate. Your body is working harder to maintain homeostasis and causes this higher resting heart rate.

of fitness. Another main reason we see athletes do well in the fall and begin to stagnate and finally decline by the spring is the lack of recovery. This rule can affect both graphs, but primarily we see the rule of recovery in the Over Training Graph. Without proper rest in-between bouts of training, all athletes will eventually break down, and fitness goes from stagnation to decline. One reason they have success in the fall and part of winter is over training has not yet fully set in. The three main outcomes of overtraining are injury, illness and decline in performance. There are a few potential warning signs that over training is setting in. One of them is a higher resting heart rate. Your body is working harder to maintain homeostasis and causes this higher resting heart rate.