| Skill Acquisition - Evidence-Based Practices for Detecting and Correcting Errors |

| By: Matthew T. Buns, Ph.D. and Tyler Naumowicz

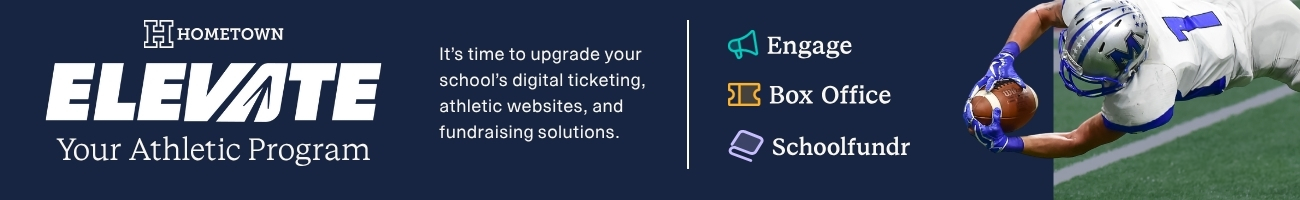

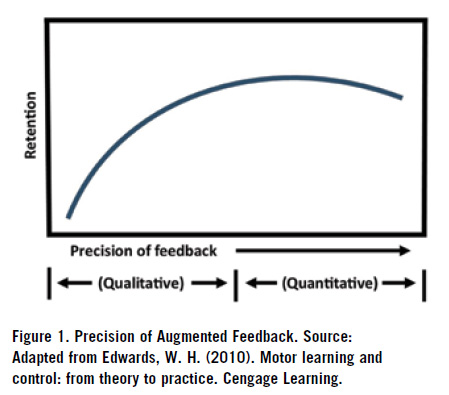

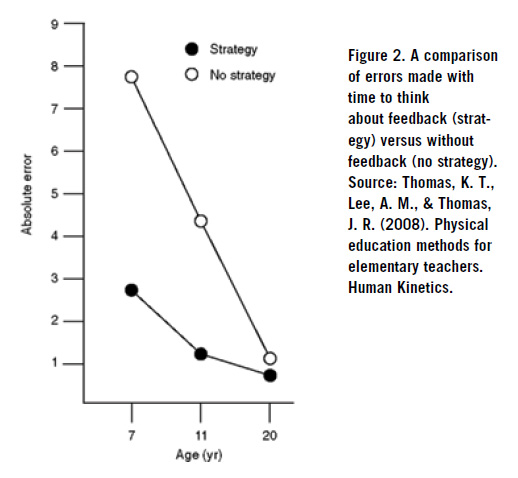

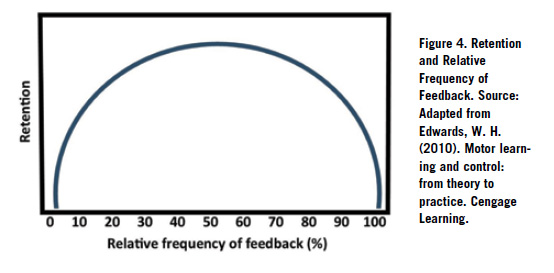

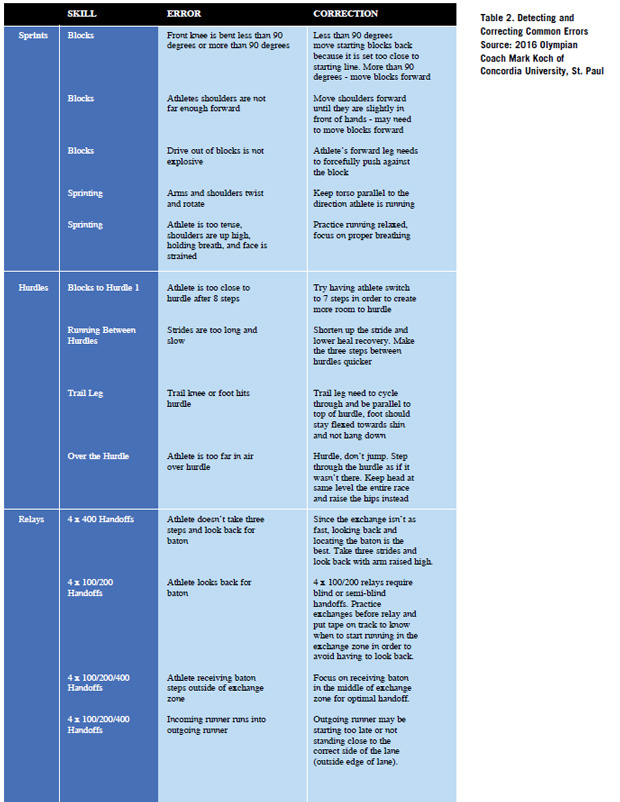

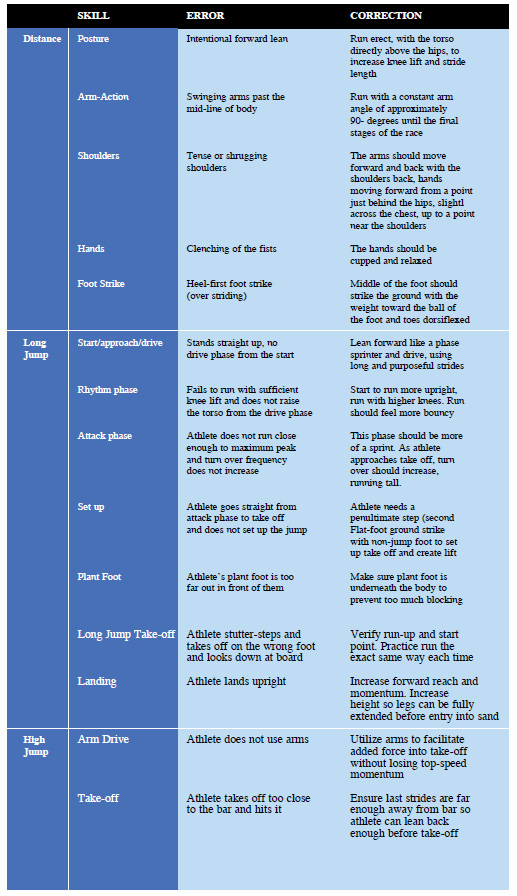

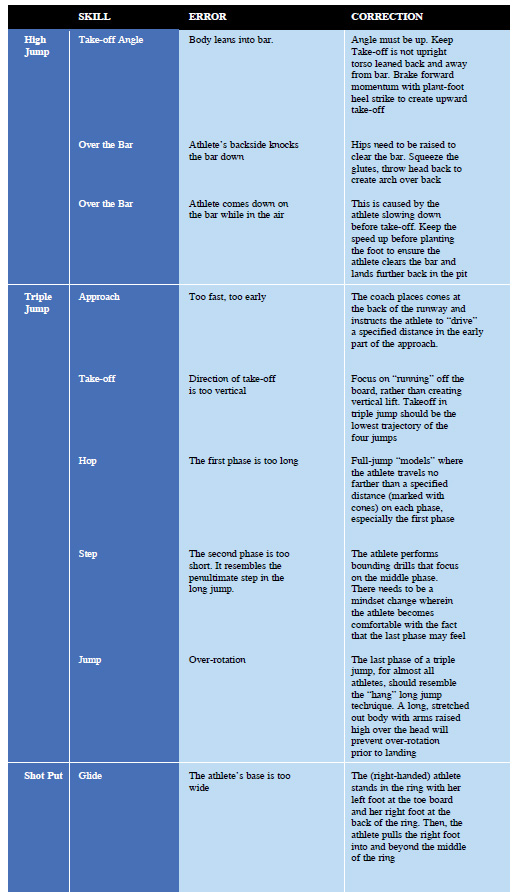

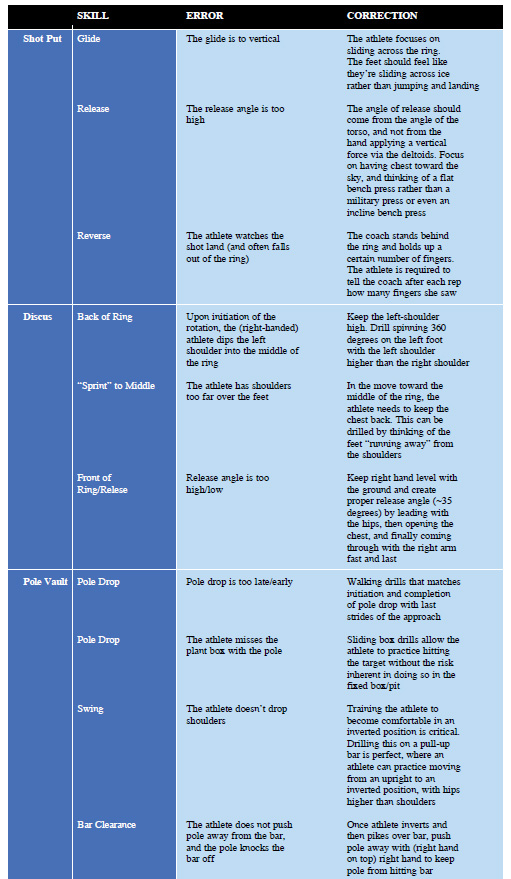

Originally Published in: Techniques Magazine Provided by: USTFCCCA THE PRECISION OF FEEDBACK Knowing the appropriate level of precision of feedback is an important consideration for track and field coaches. Precision of feedback refers to the type of information, from general ("Push harder") to specific ("Your elbow was bent two degrees too much"). The precision of feedback typically stems from two broad categories referred to as qualitative and quantitative feedback. Qualitative feedback statements contain information about the direction of an error, without referring to the magnitude of the error. Examples of qualitative feedback statements include: "You lifted your knee too far." "Bend your elbow less." "That was faster than last time." Note that in each case the feedback statement indicates a needed direction of change but not how much of a change should be made. Adding information to a feedback statement about how much change is needed increases the precision of feedback. The previous examples demonstrate increased precision by adding modifiers such as: "You lifted your knee a little too far." "Bend your elbow just a little bit less." "That was a lot faster that time." Although these qualitative feedback statements contain useful information, they still lack the informational properties most useful for initiating corrections. The precision of feedback is further increased by providing information not only concerning the direction of an error, but also about the magnitude of the error. Quantitative feedback provides information about both the direction of an error and its magnitude in numerical terms .Examples of quantitative feedback statements include these: "That was six inches too far." "Bend your elbow to a 45-degree angle." "Your time was 22.4 seconds." "Your flexion has improved by five degrees." Because these statements contain more precise information about needed corrections than do qualitative statements, both the coach and athlete are more likely to interpret it in the same way. How precise should coaches be? The research on feedback precision suggests that extrinsic feedback does not need to be extremely precise to be effective. In making decisions regarding the precision of the feedback to provide to athletes, coaches would be well advised to consider the complexity of the task relative to the usefulness of information provided by feedback. For beginners, less precise information is better because they are just trying to get a general idea of the correct relative timing pattern. At that point, all athletes need to know is general information about the relative amount and direction of their errors. You might tell a beginning high jumper that her takeoff was a bit too early. However, once she achieves a higher level of technical skill, the athlete would benefit from more precise feedback that helps her fine-tune her movements (e.g., the duration in milliseconds of her final two steps). As a general guideline, feedback should be provided with as much precision as a learner can meaningful interpret, and this typically implies using quantitative feedback as preferred to qualitative feedback. There is a point, however, where too much quantitative information can be provided in a feedback statement. Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between feedback precision and learning. Learning is enhanced as the precision of feedback becomes greater, but only up to a point. After that point, continued increases in precision become less useful to learners, who are unable to effectively respond to the more precise corrective information, which leads to diminished performance and learning. One way to promote technical skill development while increasing feedback precision is through bandwidth feed-back. To do this, establish a performance bandwidth - the amount of error you will tolerate before providing extrinsic feedback. As long as an athlete's performance remains within a tolerable zone, there's no need to give feedback. Normally coaches will want to allow a wider bandwidth and provide more general feedback for athletes who are learning a new skill than for performers whose skill level is more advanced. The bandwidth for a beginning pole vaulter, for example, would allow any movements that conform to the basic relative timing pattern. If they don't, a general feedback statement might be provided. As the athlete's skill level improves, the bandwidth would be narrowed so that feedback is given to correct even small performance deviations. If her stride length was a bit too short, you might tell her to increase it by an inch or two. Since bandwidth feedback allows you to give feedback less often, athletes derive the same benefits as they do any time you reduce feedback frequency. It is the coach's responsibility to determine a performance bandwidth for athletes that allows them to improve their technical skills as much as possible without outside assistance.   Another aspect of feedback that coaches must consider involves the timing of feedback delivery. How soon after an attempt should feedback be given? Once athletes are provided with feedback, how soon should they make their next attempt? There is no shortage of research that has been directed toward answering these questions. Athletes need sufficient time to be able to process the information provided through feedback and plan how they are going to perform their next attempt. The time period between the presentation of the verbal feedback and the athletes' subsequent performance attempt is called the postfeedback interval. Once athletes have feedback, they may need 10 or more seconds to make a plan to correct the movement before their next attempt. You can see from Figure 2 how much error is reduced when athletes who would not ordinarily use a strategy are given one to solve a specific task. Children have greater processing limitations than adults. Unfortunately, on their own, children take almost no time to consider the feedback. So coaches need to allow the time to encourage athletes to use the time to make corrections, particularly when working with young athletes. The more complex the technical skill, the more time athletes will need to evaluate their performance. By challenging athletes to evaluate their own errors and come up with possible solutions before giving them feedback, coaches facilitate both skill development and the athlete's capability of detecting and correcting their own mistakes. This means coaches may need to tolerate silence for a longer period of time when asking athletes to evaluate something relatively complex. To facilitate this process, coaches can ask athletes how they are going to execute the next attempt, or more specifically what they are going to do differently in comparison to the previous attempt. Providing more time after the feedback (the postfeedback interval) can improve performance. A common misconception about feedback is that it must be immediate. Many coaches assume that feedback is most effective immediately following performance. The reasoning behind this notion is that athletes are subject to a limited attention span. Therefore, coaches conclude that feedback should be provided immediately because the athlete will begin to forget elements of their practice attempts as soon as each is completed. Although one might expect immediate feedback to be most beneficial because it allows athletes to link the performance with the outcome or quality of the movement before their memory of the movement production fades, immediate feedback actually prevents athletes from reflecting on the movement and promotes passive learning. Table 1 outlines three common misconceptions associated with the provision of feedback and provides best practices for each misconception (Haibach, Reid, & Collier, 2011). Although feedback must occur before the next trial of a task, it does not have to occur immediately. Adams (1987) examined feedback given immediately, one day later, and one week after the performance reported no differences in learning. Immediate feedback is not important to learning motor skills. In fact, the athlete may become so reliant on the immediate feedback they will not develop the critical problem-solving skills necessary for performing the skill without the guidance of the coach. So if coaches cannot provide feedback at the end of practice or competition on a given day, they can do it before practice begins the next session. This effect is so strong that feedback given after several trials is just as good as immediate feedback provided one trial at a time.    The modality usually indicates whether the feedback is verbal, visual, or physical. Although we often think of feedback as verbal, most coaches have used many forms of nonverbal feedback. Video Feedback. Athletes may think they are performing a particular skill correctly until they see for themselves via pictures or a video. Although video feedback can be quite useful, coaches must consider several factors when using videos, such as the time period during which the video is presented, the skill level of the athlete, and whether the video is supplemented with additional feedback from the coach. Research studies have shown that video feedback used for less than five weeks resulted in no improved performance (Rose & Christina, 2006). Providing video feedback without cueing the learner to specific aspects of the movement is also ineffective, especially for the novice athlete, and may actually be detrimental to performance. This is likely because the video feedback provides "too much information" for learners who do not understand what they should be look-ing for in the video or how to interpret this information (Coker, 2009). When athletes are introduced to video feed-back, they are often more focused on their visual appearance (e.g., "How attractive do I look?") than on their movement patterns or performance. Because of this preoccupation with irrelevant factors, further instruction is ineffective until learners have adjusted to viewing themselves on video. Advanced athletes, on the other hand, know what key aspects of the movement pattern they need to focus on and can benefit from viewing videotapes of their performance with little to no supplementation. Visual Feedback. Visual feedback, which can be very beneficial during the learning process, can take the form of visual displays of kinematic feedback. The most commonly used forms of kinematic feedback are pictures, illustrations, and video replays of limb position, velocity, or acceleration (see Figure 3). For example, illustrating the changing form and correct alignment of the body throughout a pole vault attempt provides information on the movement and is supplemental to intrinsic sources of feedback. It is easy to separate the movement patterns in field events from the goal outcome, so learners of skills like these are likely to benefit from kinematic feedback. THE FREQUENCY OF FEEDBACK One final guideline has been developed concerning the effective delivery of feed-back, and that entails how frequently feedback should be provided to be of the most benefit. Traditionally, researchers and coaches assumed that the more frequently feedback was provided following performance attempts, the greater the gains in learning. This conclusion dates back over 100 years and is based in part on Thorndike's law of effect (1905) and the principles of operant conditioning. If feedback were essential in improving performance, it was argued, then obviously the more frequently feedback was delivered, the more reinforced the correct movement would become. One reason that this conclusion continues to exert an influence on many coaches thinking today is that frequent feedback does promote a practice performance. However, research conducted in the last 50 or 60 years has yielded results contradictory to the accepted wisdom that the greater frequency of feedback, the greater the degree of learning that would occur. Bilodeau and Bilodeau (1969) investigated the effects of manipulating feedback frequency on learning. In a series of studies, they were the first to observe that reducing the relative frequency of feedback enhanced learning outcomes when compared to higher relative frequencies of feedback. That is, in their studies Bilodeau and Bilodeau found that high amounts of feedback actually depressed optimal learning, whereas reducing relative frequencies of feedback improved learning outcomes. At some point, however, reducing the frequency of feedback further begins to impede further learning and, in fact, actually begins to depress learning. A generalized curve summarizing these findings is shown in Figure 4. Of note, this effect was observed only for retention measures (i.e., learning), and not for physical performance (which appeared to benefit as the frequency of feedback increased). Generally speaking, current research suggests that too much feedback is detrimental to learning (Salmoni, Schmidt, & Walter, 1984). Early in learning, more feedback is better; in fact, feedback on every attempt is great. When the athletes have practiced more, coaches can provide feedback less often, perhaps half of the time. Late in practice (or towards the end of a season) only give feedback once in a while. If you averaged the amount of feedback across learning, from early to late, the average would be that 50 percent of the attempts received feedback. The reason is that athletes can become dependent on extrinsic feedback, which means that they do not learn to detect and correct errors themselves. For example, a javelin thrower receives feedback after each of 10 attempts. If the feedback is "Keep the javelin lower," what do you think the athlete will try to do on his next throw? Keep the javelin lower. If he hears "Follow through better," he will attempt to follow through better on the next attempt. In other words, each time the athlete receives extrinsic feedback, he immediately tries to incorporate the feedback on the next attempt. The problem is that by making these moment-to-moment corrections, the athlete is unable to achieve much stability in his performance. As a result, he doesn't learn as much about the relationship between what he is doing and the result that he is getting. Although performance may appear to be improving with more frequent extrinsic feedback, the athlete is probably not learning why this is happening. When he ceases to get receive feedback, the athlete's performance is likely to regress to its previous level. Thus, excessive feedback promotes passive learning, so that the athlete does not develop the critical problem-solving skills necessary for performing the skill without the guidance of the coach. To be independent performers, athletes must learn to detect and correct their own errors. One way to increase the amount of feedback coaches provide without overloading athletes with too much information is to use summary feedback or average feedback after a practice session. Summary feedback informs athletes how they performed on each of several practice attempts, while average feedback highlights general tendencies in their performance (Edwards, 2010). For a long jumper's last five jumps, summary feedback might be that her plant foot landed beyond the takeoff board on her first, third, fourth, and fifth jumps and on the takeoff board during her second jump. Average feedback for the athlete might be that her plant foot landed slightly beyond the takeoff board for the five attempts. An important issue to consider when giving summary feedback or average feedback is the number of performance attempts to include in the feedback statement. Generally speaking, the more complex the technical skill or the less experienced the athlete, the fewer attempts you should include in the feedback. PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR DETECTING AND CORRECTING ERRORS In light of the shortcomings associated with too much feedback, coaches are tasked with the responsibility of deciding how often to provide to facilitate rather than impair an athletes' skill development. One way to do this is to reduce the frequency of extrinsic feedback whenever it becomes apparent an athlete is becoming more proficient. To provide helpful feedback, coaches must be able to both detect errors in athletes' performance (e.g., see a high jumper turning his back before jumping over) and offer possible solutions for the problem (e.g., ensure run-up curve is not too tight or lean is slightly into the curve). The process of helping athlete's correct errors begins with observing and evaluating performance. Coaches must develop a critical eye for proper mechanics, correct errors, and praise progress. One of the most common coaching mistakes is providing inaccurate feedback and advice on how to correct errors. As a rule, coaches should see the error repeated more than just occasionally before attempting to correct it (American Sport Education Program, 2008). Although there is no substitute for a coaches own mastery of the skill, Koch (2017) offers practical considerations detecting and correcting errors in track and field. These include common performance errors in track and field and possible feedback statements that could be used for fixing the errors (Table 2).     As long as athletes are attending to relevant sources of intrinsic feedback, they don't need (or usually don't want) additional information from the coach. Therefore, a good rule offered by Edwards (2011) to keep in mind when considering when to give feedback is "When in doubt, be quiet." Recent research indicates that athletes benefit more from feedback when they ask for it than when someone else (e.g., the coach) decides they need it. By establishing good communication with athletes, coaches should be able to discern when they need feedback and when they don't. When athletes enjoy open communication with the coach, they are more likely to request extrinsic feedback when they need it. CONCLUSION As aforementioned, feedback is one of the most important factors in skill acquisition and one of the most difficult for coaches to master. Feedback helps guide the performer toward executing the proper movement pattern, motivates the athletes, and reinforces successful performance. However, findings also suggest that coaches should resist the temptation to provide feedback more frequently and instead allow athletes to practice their skills on their own. A general rule is for the coach to provide feedback more frequently during initial learning and progressively less frequently as skill levels improve. Just as practice should be designed around the individual and the task, feedback should be individualized to the learner and the task. The more difficult the technical skill, the more likely it is for athletes to request a coaches feedback. The most important principle to remember when it comes to deciding how much feedback to give is "Keep it simple." Simple, however, does not mean simplistic. On the contrary, feedback should provide athletes with the most helpful information possible. Keeping extrinsic feedback simple means giving athletes the type of feedback that is most relevant at a particular moment. In other words, quality is more important than quantity. The coach's goal is to provide athletes with the type, amount, and frequency of extrinsic feedback that forces them to attend to the intrinsic feedback - the feedback they sense themselves - that is relevant for successful performance. The more athletes do this, the better they will be able to perform in competition without assistance. One of the major responsibilities of a coach is to provide feedback, but at the same time, help athletes learn to detect and correct their own errors. Ironically, good coaches may eventually coach themselves out of a job! REFERENCES Adams, J.A. (1987). Historical review and appraisal of research on the learning, retention, and transfer of human motor skills. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 41-74 American Sport Education Program (2008). Coaching Youth Track and Field. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Bennett-Yea, S., Bowler, V., Durden, W, Lenox, D., Murphy, R., Sirianni, K, & Zackodnik (2007). Athletics Coaching Guide: Planning an Athletics Training and Competition Season. Special Olympics. Bilodeau, I.M. (1966). Information feedback. In E.A. Bilodeau (Ed.), Acquisition of skill (pp. 225296). New York: Academic Press. Coker, C.A. (2009). Motor learning and control for practitioners. New York: McGraw-Hill. Edwards, W. H. (2010). Motor learning and control: from theory to practice. Cengage Learning. Haibach, P., Reid, G., & Collier, D. (2011). Motor learning and development. Human Kinetics. Rose, D.J., & Christina, R.W. (2006). A multilevel approach to the study of motor control and learning (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Pearson Benjamin Cummings. Thomas, K T., Lee, A. M., & Thomas, J. R. (2008). Physical education methods for elementary teachers. Human Kinetics. Thomas, J.R. (2000). C.H. McCloy Lecture: Children's control, learning, and per-formance of motor skills. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 71, 1-9. Thomas, J.R. M.A. Solmon, MA., & Mitchell, B. (1979). Precision knowledge of results and motor performance; Relationship to age. Research Quarterly for Exercise and sport, 50, 687-698. Matthew Buns is an Assistant Cross Country and Track and Field Coach; Associate Professor of Kinesiology and Health Science, Concordia University, St. Paul, MN Tyler Naumowicz is a Student-Assistant Track and Field Coach at Concordia University, St. Paul, MN |