| Psychological Factors Contributing to Injury

By: Matthew Buns PH. D. Originally Published in Techniques Magazine - USTFCCCA

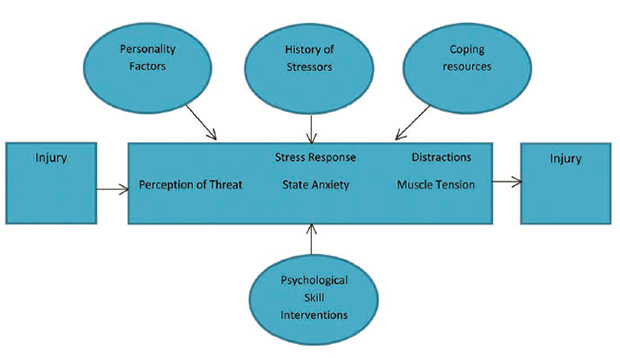

Physical factors are the primary cause of athletic injuries, but psychological factors also contribute. Sport psychologists have helped clarify the role that psychological factors play in athletic injuries. Figure 1 shows a simplified version of their model. You can see that in this model, the relation between athletic injuries and psychological factors centers on stress. In particular, a potentially stressful track and field situation (e.g., competition, important practice, poor performance) can contribute to injury, depending on the athlete and how threatening he or she perceives the situation to be. A situation perceived as threatening increases state anxiety, which causes a variety of changes in focus or attention and muscle tension (e.g., distraction and tightening up). This in turn leads to an increased chance of injury. See figure 1.

How Do Injuries Happen? As mentioned, physical factors are the primary causes of track and field injuries. However, psychological factors have also been found to play a role. Personality factors, stress levels and certain predisposing attitudes have an been identified (Williams & Andersen, 2007). As psychological antecedents to athletic injuries. In fact, in one recent study, up to 18 percent of time loss because of injury was explained by psychosocial factors (Smith, Ptacek, & Patterson, 2000). Personality Factors. Personality traits were among the first psychological factors to be associated with athletic injuries. Investigators wanted to understand whether such traits as self-concept, introversion-extroversion, and tough-mindedness were related to injury. For example, would runners with low self-concepts have higher injury rates than their counterparts with high self-concepts? Unfortunately, most of the research on personality and injury has suffered from inconsistency and the problems that have plagued sport personality research in general (Feltz, 1984). Of course, this does not mean that personality is not related to track & field injury rates; it means that to date we have not successfully identified or measured the particular personality characteristics associated with injury. In fact, recent evidence (Ford, Eklund & Gordon, 2000) shows that personality factors such as optimism, self-esteem, hardiness and trait anxiety do play a role in athletic injuries.

Stress Levels. Stress levels, on the other hand, have been identified as important antecedents of athletic injuries. Research has examined the relation between life stress and injury rates (Andersen & Williams, 1988). Measures of these stresses focus on major life changes, such as losing a loved one, moving to a different town, getting married, or experiencing a change in economic status. Such minor stressors and daily hassles as driving in traffic have also been studied. Overall, the evidence suggests that athletes with higher level of stress experience more injuries than those with less stress in their lives, with 85 percent of the studies verifying that this relationship exists (Williams & Andersen, 2007). Thus, track & field coaches should ask about major changes and stressors in athletes' lives and, when such changes occur, carefully monitor and adjust training regimens as well as provide psychological support. Stress and injuries are related in complex ways. A study of 452 male and female high school athletes addressed the relation between stressful life events; social and emotional support from family, friends, and coaches; coping skills; and the number of days athletes could not participate in their sport because of injury (Smith, Smoll & Ptacek, 1990). Life stress was associated with athletic injures in the specific subgroup of athletes who had both low levels of social support and low coping skills. These results suggest that when an athlete possessing few coping skills and little social support experiences major life changes, he or she is at a greater risk of injury Similarly, athletes who have low self-esteem, are pessimistic, anxious, and who have low self-esteem, are pessimistic, anxious, and low in hardiness (Ford et al., 2000) experience more athletic injuries or lose more time as a result of their injuries. Coaches should be on the lookout for these at-risk individuals. This finding supports the Andersen and Williams model (Figure 1), emphasizing the importance of looking at the multiple psychological factors in the stress-injury relationship. Research has identified the specific stress sources for athletes when injured and when rehabilitating from injury (Podlog & Eklund, 2006). Interestingly, the great-est sources of stress were not the result of the physical aspects of injuries. Rather, psychological reactions (e.g., fear of injury, feeling that hopes and dreams were shattered, watching others get to perform) and social concerns (e.g., lack of attention, isolation, negative relationships) were mentioned more often as stressors. Being familiar with these stress sources is important for track & field coaches working with injured athletes. Teaching stress management techniques not only may help athletes perform more effectively but also may reduce their risk of injury and illness. In a well-designed clinical trials study, collegiate athletes who were randomly assigned to stress management training versus control condition experienced fewer days lost to injury or illness across a season (Perna, Antoni, Baum, Gordon, & Schneiderman, 2003). The relationship between stress and injury Understanding why athletes who experience high stress in life are more prone to injury can significantly help track & field coaches in designing effective programs to deal with stress reactions and injury prevention. Two major theories have been advanced to explain the stress-injury relationship. Attentional. One promising view is that stress disrupts an athlete's attention by reducing the peripheral attention (Williams, Tonyman & Andersen, 1991). Thus, a long-distance runner under great stress may not see a moving vehicle or misguided throwing implement and is struck. When his stress levels are lower, the runner has a wider field of peripheral attention and is able to see the object in time to avoid being struck and subsequent injury. It has also been suggested that increased state anxiety causes distraction and irrelevant thoughts. For instance, a cross country runner who practices after an argument with a peer might be inattentive to the running path and step into a hole, twisting her ankle. Other Psychologically based explanations for injury In addition to stress, sport psychologist working with injured athletes have identified certain attitudes that predispose players to injury. Rotella and Heyman (1986) observed that attitudes held by some coaches—such as "act tough and always give 110 percent" or "if you're injured, you're worthless"—can increase the probability of athlete injury. Act Tough and Give 110 percent. Slogans such as "Go hard or go home," "No pain, no gain," and "Go for the burn" typify the 110-percent-effort orientation that many coaches promote. By rewarding such effort without also emphasizing the need to recognize and accept injuries, track & field coaches encourage their athletes to compete hurt or take undue risks. A hurdler, for instance, may be repeatedly rewarded for competing through hip pain on a given race. He becomes even more daring, competing in further events or practices until one day he sustains a serious, insurmountable injury.

If You're Injured, You're Worthless. Some athletes learn to feel worthless if they are hurt, an attitude that develops in several ways. Track & field coaches may convey, consciously or otherwise, that winning is more important than the athlete's wellbeing. When an athlete is hurt, they no longer contribute toward winning. Thus, the coach has no use for the athlete—and the athlete quickly picks up on this. Athletes want to feel worthy (like winners), so they practice or compete while hurt and sustain even worse injuries. A less direct way of conveying this attitude that injury means worthlessness is to say the "correct" thing (e.g., "Tell me when you're hurting! Your health is more important than winning") but then act very differently when an athlete is hurt. The athlete is ignored, which tells him that to be hurt is to be less worthy. Athletes quickly adopt that attitude that they should perform even when they are hurt. Conclusion Psychological factors influence the incidence of injury, response to injury, and injury recovery. Professionals in our field must be prepared to initiate coaching practices that help prevent injuries, assist in the process of coping with injury, and provide supportive psychological environments to facilitate injury recovery. Psychological factors, including stress and certain attitudes, can predispose track & field athletes to injuries. Coaches must recognize antecedent conditions, especially major life stressors, in athletes who have poor coping skills and little social support. When high levels of stress are identified, stress management procedures should be implemented and training regimens adjusted. Athletes must learn to distinguish between the normal discomfort of training and the pain of injury. They should also understand that a "no pain, no gain" attitude can predispose them to injury. References Andersen, M.B., & Williams, J.M. (1988). A model of stress and athletic injury: Prediction and prevention. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 10,297-306. Ford, I.W., Eklund, R.C., & Gordan, S. (2000). An examination of psychosocial variables moderating the relationship between life stress and injury time-loss among athletes of a high standard. Journal of Sports Sciences, 18(5), 301-312. Marti, B., Vader, J. P., Minder, C. E., & Abelin, T. (1988). On the epidemiology of running injuries. The 1984 bern grand-prix study. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 16, 285-294. Petri, T.A., & Perna, E (2004). Psychology of injury: Theory, research and practice. In T. Morris & J. Summers (Eds.), Sport psychology: Themy, application and issues (2nd ed., pp. 547-571), Milton, Australia: Wiley. Perna, EM., Antoni, M.H., Baum, A., Gordon, P., & Schneiderman, N. (2003). Cognitive behavioral stress management effects of injury and illness among competitive athletes: A randomized clinical trial. Annuals of Behavioral medicine, 25(1), 66-73. Podlog, L., & Eklund, R.C. (2006). A longitudinal investigation of competitive athletes return to sport following injury. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 18,44-68. Rotella, RJ., & Heyman, S.R. (1986). Stress, injury and the psychological rehabilitation of athletes. In J.M. Williams (Ed.), Applied sport psychology: Personal growth to peak performance (pp. 343-364). Palo Alto, CA: Mayfield. Smith, RE., Ptacek, J.T., & Patterson, E. (2000). Moderator effects of cognitive and somatic trait anxiety on the relation between life stress and physical injuries. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 13, 269-288. Smith, R.E., Smoll, EL., & Schutz, R.W. (1990). Measurement and correlates of sport-specific cognitive and somatic trait anxiety: The Sport Anxiety Scale. Anxiety Research, 2, 263-280. Williams, J.M., & Andersen, M.B. (2007). Psychosocial antecedents of sport injury and interventions for risk reduction. In G. Tennebaum & R.C. Edklund (Eds.), Handbook of sport psychology (3rd ed., pp. 379-403). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Williams, J.M., Tonyman, P., & Andersen, M.B. (1991). The effects of stressors and coping resources on anxiety and peripheral narrowing Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 3, 126-141. Dr Matthew Buns is a faculty member in Concordia's Health and Human Performance Department. His teaching emphasis is in physical education and exercise psychology and his research interests focus on motor development, curriculum and school wellness policy.

|

This is not to say that athletes should not throw the shot put hard or extend themselves in the long jump. But giving 110 percent should not be emphasized so much that athletes take undue risks—such as performing in extreme pain and increasing their chances of severe injuries. Effective track & field training does involve discomfort, but athletes must be taught to distinguish the normal discomfort accompanying overload and increased training volume from the pain accompanying the onset of injuries.

This is not to say that athletes should not throw the shot put hard or extend themselves in the long jump. But giving 110 percent should not be emphasized so much that athletes take undue risks—such as performing in extreme pain and increasing their chances of severe injuries. Effective track & field training does involve discomfort, but athletes must be taught to distinguish the normal discomfort accompanying overload and increased training volume from the pain accompanying the onset of injuries.