| Peripheral Issues in Combined Event and Multi-event Training Design |

| Originally Published in: Techniques Magazine

Provided by: USTFCCCA

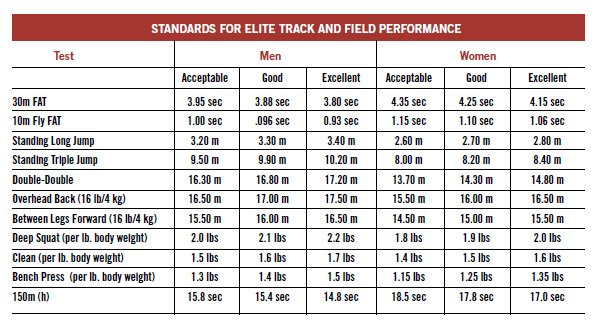

In this chapter taken from the combined events specialist certification course curriculum, many of the peripheral issues that impact an athlete's development are addressed. Topics include record keeping, testing, rest and restoration and lifestyle issues among others. RECORD KEEPING Quantification. Quantification is the process of planning and recording training volumes. The quantification process is typically concerned with quantifying volumes or intensities. Quantifying Volumes. The quantification of volume can take many forms. Units of measure might be as numbers of sets or repetitions performed, meters run, total weight lifted, number of foot contacts, or time spent in work. Quantifying Intensities. The quantification of intensity can take many forms as well. In some training modalities, intensities are measurable. The intensity measurements most used are percentages of maximal effort in weight training exercises, running efforts, or other training activities. At other times, intensity is determined solely by the nature of the exercise chosen, is not readily measurable, and is highly subjective. Still subjective intensity evaluation can be done with some accuracy if the demands of the work are understood. For example, a decision that depth jumps are more intense than in place jumps may be subjective to some degree, but understanding the increased stresses associated with the depth jumps makes this decision likely to be accurate. Indexing. Indexing is a systematic approach to the process of planning and recording volumes, or the combined effects of volume and intensity. Intensities may be evaluated objectively or subjectively. An example of a simple indexing system for run training may include multiplying the distance run by the percentage of personal best time (or some factor thereof). This would characterize training with some numerical factor that considers volume and intensity. Various types of multi-jump exercises could be assigned some intensity factor, and the number of contacts performed could be multiplied by this factor to form another such system. TESTING Testing is the measurement of performances in controlled environments in order to gain accurate, objective data and objective means of evaluation. Reasons for Testing. Reasons for testing include talent identification, program analysis, evaluation of balance and development of physical performance components, and performance prediction. Administration of Testing. Testing should not be done haphazardly, as information gained in this way cannot be used for the purposes intended with any reliability. Tests should be valid, and the testing environment should be controlled as much as possible. This includes standardizing measurement, number of trials, test sequence, equipment and warmup practices. Commonly Used Tests. Common tests used are listed below. A coach may employ any or all at certain times in the training regimen. 30 Meter Sprint. The 30 meter sprint test of accelerative power. The athlete runs 30 meters for time from a stationary start. Fly Tests. Fly tests are tests of absolute speed. The athlete runs a particular distance (usually 10 or 30 meters) for time, after having previously accelerated through a designated (usually 20 or 30 meter) acceleration zone. Standing Long Jump. A short bounding exercise, the standing long jump is a test of starting power and reactive strength. The athlete performs a single jump for distance from a standing start. Standing Triple Jump. A short bounding exercise, the standing triple jump is a test of reactive strength, power, and coordination. The athlete, from a double legged standing start, performs three jumps. The test begins with a double leg takeoff, then a right-left or left-right contact pattern prior to landing. Double-Double. A short bounding exercise, the double-double is a complex test of reactive strength, power, and coordination. The athlete, from a double legged standing start, performs five jumps. The test begins with a double leg takeoff, then a right-right-left-left or left-left-right-right contact pattern prior to landing. Overhead Back Shot Throw. A multi-throw exercise, the overhead back shot throw is a test of power and coordination. The athlete stands on the shot toeboard facing away from the sector with the shot in both hands. The athlete then squats, lowers the shot below the waist, then throws the shot overhead for distance. Between the Legs Forward Shot Throw. A multi-throw exercise, the between the leg forward shot throw is a test of power and coordination. The athlete stands on the shot toeboard facing the sector with the shot in both hands. The athlete then squats, lowers the shot below the waist, and then throws the shot forward for distance. General Strength Tests. General strength exercises can be used to construct tests of general strength qualities, coordination, and body control. The athlete is asked to perform as many repetitions of a given general strength exercise as possible in a certain period of time. A 30 second sit-up test is an example. Cooper's Tests. To determine endurance potential, athletes are asked to run for a designated time period, with distance achieved being the variable measured. Time Trials. Depending upon an athlete's event, time trials of certain distances are useful to measure progress and predict performance. Weight Training Exercise Tests. These are tests of absolute strength and power using weight training exercises as the measurement tool. Safety in testing should always be a priority. Various protocols can be used, and these typically take three forms: 1. Single Repetition Maximums. These tests are designed to determine the maximum amount of weight an athlete can use in a single successful repetition. While these tests have use, they are risky and to be used with care at appropriate times when athletes are prepared for such tests. 2. Multiple Repetition Maximums. These tests are designed to determine the maximum amount of weight an athlete can use when successfully performing a set of some designated number of repetitions. These tests, while demanding, entail less risk than single repetition maximum tests. 3. Projected Maximums. These tests require the athlete to perform as many repetitions as possible with a designated load. This data is then manipulated mathematically to determine a projected single repetition maximum. Projected maximum tests are the safest form of weight testing. It should be understood that in the early stages of training, the single repetition maximum projection does not represent the athlete's abilities at that point, but is a measure of progress and a value to consummate as training progresses. Periodization of Testing. Testing should be periodized with respect to the principles of training. Over time, tests should progress from general to specific and simple to complex. While a core battery of pertinent tests should be regularly administered, other tests from outside this group should be done from time to time. The scheduling of these tests should be done with respect to the qualities being tested and the sequencing of training. Scheduling of Testing. Scheduling of testing is an important variable. Training done in the immediate past is likely to have an effect on the results. Most systems test at the same relative time during each training cycle for this reason. For example, it is common to test each cycle during the rest period, or during the first work period of the cycle. Testing is a low volume, high intensity activity. These demands should be considered in the design of training. A testing day is not necessarily an easy day. TESTING AND ADAPTATION Timeframes. Adaptation does not occur immediately, so completing a cycle of training for a particular quality does not mean that this quality will show improvement immediately upon the completion of that cycle. When a test is new, improvements on the test improve rapidly (the Hawthorne effect). This should be considered when evaluating test results. Result Suppression. Sequential training may suppress the emergence of improved qualities, and improvements on related tests. For example, a cycle of speed development work may not show improvements in this quality as measured in testing if the next cycle features heavy absolute strength work. This does not mean that the speed cycle has failed; these qualities are likely to emerge later. For this reason, test results are often specific only to one particular training program, or one particular time of year. Testing and Performance Prediction. Achievement of certain performance levels in the various physical performance components is necessary to attain elite performances in track and field. When these markers have not been attained elite performances should not be expected. REST AND RESTORATION Restoration. Facilitating restoration of the body is an important part of planning training. Restoring the body not only assists in injury prevention and general comfort, but also enhances the effectiveness and quality of training, and makes one able to handle larger training loads.

FORMS OF RESTORATION Rest. Rest is the total absence of training activity. Active Rest. Active rest is the prescription of some activity of a nature different from traditional training, such as another sport. Restoration Modalities. Restoration modalities are activities that help to eliminate soreness and accelerate recovery from exercise. Restorative modalities include whirlpool (hot or cold), ice baths, sauna, and massage. Periodization of Restoration. Restoration can be scheduled at any time, but it is most frequently scheduled after more intense work. It is crucial to success at high levels to consider restoration as part of training, not an addendum to it. LIFESTYLE ISSUES Sleep. Good sleep habits are crucial to the success of the training plan. Adequate sleep (eight to ten hours per day) is essential to permit regeneration. Also, adequate sleep, especially the hours before midnight, is necessary to allow healthy production of anabolic hormones key to recovery. Nutrition. A complete discussion of nutrition is beyond the scope of this text, however we will examine some general guidelines for combined event athlete's nutritive needs. A proper nutritional plan is essential to the success of the training program. Athletes should eat a variety of nutritious foods and avoid unhealthy choices. The nutritional status of the athlete greatly determines the effectiveness of the training and the ability to handle large training loads. Following are general suggestions for the diets of athletes. The Food Groups. Choosing from and balancing the traditional four food groups (fruits and vegetables, dairy, meats and grains) is a simple, effective way to plan for general nutrition needs. Avoiding Processed Foods. Highly processed foods (such as sugars, oils and flours) should be avoided in excess. They are not recognized by the body as foods, and are difficult for the body to process. Diet Construction. The diet should be fairly low in fats and simple carbohydrates. It should be rich in vitamins, minerals, complex carbohydrates and protein. Food Preparations. Simply cooked meals or raw foods are nutritionally superior to complex preparations. Meal Distribution. Ideally, several small meals scattered throughout the day is most effective for the athlete. The Importance of Breakfast. Breakfast is extremely important, and should contain some protein rich food. Hydration. While a complete discussion of the function of water is the body's chemical reactions is beyond the scope of this text, suffice it to say that sufficient water intake is crucial to maintaining efficiency in nearly all body functions. It is equally important to adaptations from training. Following are some basic guidelines for combined event athlete's hydration needs. Water Intake. Athletes should drink approximately one gallon of water a day as a minimum. This water is best taken in small servings scattered throughout the day.

Environmental Changes. Increased water intake may be necessary during hot or dry weather, especially when windy. Air travel tends to dehydrate the body quickly, so increasing water intake prior to such trips is advised. Diuretic Use. Intake of coffee, tea and carbonated drinks should be limited or eliminated. These act as diuretics and tend to dehydrate the body. Supplementation. A complete discussion of nutritional and other supplements is beyond the scope of this text, however we will examine some general guidelines for supplement use. Seek Trusted Expertise. Take extreme care and seek trusted expertise when choosing supplements and planning the supplementation program. Only choose supplements produced by reputable manufacturers. Absorbability. Consider not only the contents of any supplement, but also how absorbable it is to the body. Nutritional Deficits. Even well planned diets may be nutritionally deficient and may need supplementation, because many foods are grown in denatured soils or are nutritionally deficient for other reasons. Supplementation/Diet Relationships. Supplementation is not a substitute for a good diet. Many supplements require a good diet as a transport system for supplemented nutrients. Dangers. Many legal supplements contain dangerous substances and should be avoided, and may become even more dangerous when combined with supplements that may be safe otherwise. Extreme care should be taken and labels read closely when purchasing these products. Androgenic Ingredients. Supplements may contain ingredients that may trigger positive drug tests. One should be familiar with the list of banned substances when using certain types of supplements. Boo Schexnayder was primarily responsible for the content of the majority of the Track & Field Academy's course curriculum including this excerpt from the Combined Events Specialist Certification course text. |