| Overtraining in Sport - With an Emphasis on Distance Runners |

| By: Molly Hirt

Originally Published in: Techniques Magazine Provided by: USTFCCCA

McKenzie (1923) reported that there are three different kinds of exhaustion after exercise: (1) acute exhaustion accompanied by marked breathlessness, from which recovery is rapid; (2) fatigue of the whole musculature system, which requires a day or two of rest; and (3) chronic fatigue, which he refers to as `staleness,' and from which recovery was prolonged and could last weeks or even months. A decrease in performance is observed in an athlete who has overtrained. The natural response of many athletes, particularly runners, is to train even harder, believing that any poor performance was due to being undertrained. This attributional process simply exacerbates the problem, and the vicious cycle of overtraining continues. Once an athlete is even mildly overtrained, they are already past peak condition; at this point, the only way to recover is to rest until the body is able to rejuvenate itself, and the desire to compete and run returns (Noakes, 2003). Noakes (2003) believes that one of the critical reasons that runners are prone to overtraining is because of their lack of ability to make an object assessment of their performance capabilities. It is difficult to accept and understand the notion that an athlete has a natural, genetic performance range. The American dream has carried over into the mentality of many runners, who believe that the harder they train and run, the more successful they will be. However, this is not always the case. Foster and Lehmann (1997) have pro-posed a set of risk factors that are characteristic of athletes susceptible to over-training, which include: training very intensely for a protracted period of time, and running a series of races in short succession following an intensive training block. When runners do not have adequate recovery between high-intensity training sessions or perform the same type of training monotonously, they increase their risk of developing over-training syndrome (Foster & Lehmann, 1997). Research conducted by Costill et al. (1985) found that the peak muscle power of swimmers was lowest when they trained the most. Muscle power was then found to increase progressively during a seven-day taper before competition. One of the reasons for this decreased power during intense training is due to the brain's inability to recruit enough muscle fibers, which contributes to the fatigue that develops (Noakes, 2003). This reaction serves as a protective mechanism produced by the body to help prevent the athlete from continuing to exercise and train when in the overtrained state (Noakes, 2003).

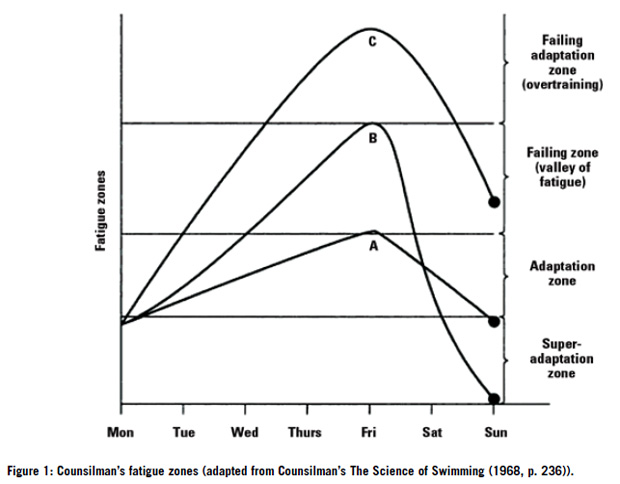

With regard to overtraining, Doc Counsilman stressed that as long as the training performance was stable or improving, then feeling tired doesn't necessarily mean that the athlete has done too much (Counsilman, 1968). He argued that during the intense, precompetition phase of training, his athletes should not fully recover completely before the next workout (Counsilman, 1968). This method of training keeps athletes in a "valley of fatigue" during the training week before days of reduced training over the weekend (Counsilman, 1968). Counsilman found this training method to produce good long-term results. The Science of Swimming written by Counsilman uses Figure 1 to demonstrate the fatigue levels of different athletes who trained hard for five consecutive days, and then recovered on Saturday and Sunday. By Friday, each of the athletes reached a "valley of fatigue," which is also referred to as overreaching training (Counsilman, 1968). Athlete A becomes mildly fatigued by Friday, barely reaching the failing zone (valley of fatigue). On Sunday, the fatigue level returns to what it was on the previous Monday. Athlete B pushes him/herself to the limit of the failing zone (Counsilman, 1968). However, when this athlete recovers over the weekend, the body has superadapted to a fatigue level that is even lower than the previous Monday (Counsilman, 1968). This situation reflects the athlete's increase in fitness and ability to resist fatigue while training, which is exactly what a coach is looking for during a training week. Athlete C trains the hardest throughout the week and dips into the failing adaptation zone (Counsilman, 1968). By Sunday, the athlete has not fully recovered from the previous week's training (the level of fatigue was higher on Sunday than the previous Monday). If the athlete continues to train hard on Monday without allowing his/her body to recovery, then the athlete will progress from overreaching to overtraining (Counsilman, 1968). SYMPTOMS OF OVERTRAINING The early signs of overtraining are generalized fatigue, recurrent headaches, diarrhea, weight loss, sexual disinterest, and a loss of appetite for food or work (Noakes, 2003). Many athletes who are overtrained also have difficulty sleeping, which is often characterized by early morning wakening and an inability to relax (Noakes, 2003). Heiss (1971) found that overtrained athletes have an increased susceptibility to infection. Therefore, respiratory inflections, swelling of lymph glands, colds, or the flu are common among overtrained athletes due to a weakened immune system. Athletes often feel sluggish and have heavy legs when they are exercising. Muscle soreness is common during a given training block due to muscle cell damage and glycogen depletion. Moreover, with overtraining, athletes' heavy legs are inappropriately sore, and this soreness does not pass as a training run progresses (Noakes, 2003). When athletes are experiencing full-blown overtraining, their legs do not recover within 24-48 hours and instead require extensive periods of time before the symptoms of overtraining are alleviated. With overtraining, the athlete is unable to let their body recover, so there is persistent muscle damage and depletion of energy stores (Noakes, 2003). Sjostrom et al. (1987) compared muscle biopsies of a group of runners before and after a seven-week intense training period. A considerable difference was seen between the muscle fibers before and after. After the training period, the average muscle-fiber size was reduced and the type II (fast-twitch) muscle fibers were more susceptible to injury.

Based on his experience as a coach, Counsilman (1968) claims that the primary indicator of overtraining in an athlete is a decrease in performance during training and competition. Newton (1947) claims that one of the signs of staleness is the inability to produce your best when you are in good shape. When an athlete is overtrained, for a given exercise bout at the same intensity, the athlete's heart rate is higher than when they are not overtrained. The early morning pulse rate of overtrained athletes has also been found to be increased as well. The reason for the increased heart rate is unknown, but is hypothesized to be due to fatigue of the heart muscle (Dressendorfer et al., 1985) or heightened activity of the sympathetic nervous system, reflecting the increased stress on the body and inadequate recovery (Noakes, 2003). One of the greatest female distance runners in history, Grete Waitz, claimed, "I judge my fatigue more by my moods. If it's hard to sleep or I am cranky, impatient or annoyed, I am probably overtraining. In my case, family and friends often know when I am overtraining even before I do" (Waitz & Averbuch, 1986). One of the main difficulties in determining whether overtraining is occurring is that there is no physiological test that can be done to confirm it. Barron et al. (1985) investigated whether or not overtrained runners were able to appropriately secrete cortisol in response to the biochemical demands placed on the body. In his experiment, he injected over-trained runners with insulin to induce a hypoglycemic state, and found that over-trained runners demonstrated an abnormal cortisol response (Barron et al., 1985). The athletes were unable to increase their blood cortisol levels in response to hypoglycemia. The inability to increase cortisol was found to be due to exhaustion by the hypothalamus (Barron et al., 1985). In another study, MacConnie et al. (1986) reported that male runners who were overtrained demonstrated reduced luteinizing hormone release from the pituitary. Costill et al. (1988) investigated whether or not there were differences in biological markers (i.e., blood concentrations of a variety of hormones, chemicals relating to muscle damage, or markers of immune function) between athletes who are over-trained and those who are not. The result of their study did not find any significant predictors of the onset of overtraining. Therefore, while there may be some physiological differences between athletes who are overtrained and those who are not, there has yet to be any definitive evidence that biochemical markers can differentiate overtrained athletes from those who are training intensively, but have adapted appropriately to the heavier training load (Noakes, 2003). It is difficult to conduct research on overtraining because it is difficult to get approval from the IRB, since participants It is difficult to conduct research on overtraining because it is difficult to get approval from the IRB, since participants in these studies have to perform exercise until exhaustion. Also, since no definitive marker of overtraining has currently been identified, how do researchers definitely determine if an athlete is truly overtrained or not?

DIFFERENTIATING OVERTRAINING FROM OTHER CONDITIONS Hypothyroidism is a condition that has similar symptoms to overtraining syndrome. Common symptoms associated with hypothyroidism include fatigue, muscle weakness, pain, stiffness, and depression (Mayo Clinic, 2013). Diagnosis of hypothyroidism is possible by appropriate blood tests, in particular, the immunometric thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) assay. The similarities between the symptoms of overtraining and hypothyroidism make it important to differentiate between them, because the treatment for each of these conditions is different. Athletes with hypothyroidism do not want to be resting and taking time off from running because they think that they are overtraining, for it will not alleviate their symptoms. Instead, they should be taking the synthetic thyroid hormone levothyroxine to help treat their condition. Another condition that is important to differentiate from overtraining is post-viral fatigue syndrome. This condition is characterized by fatigue following a viral infection. Symptoms commonly associated with this syndrome are fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, neurocognitive difficulties, and mood disturbance (Ho-Yen, 1990). Patients with this condition also experience nausea, loss of appetite, and wakeup from sleep feeling unrefreshed (Ho-Yen, 1990). While there is no cure for post-viral fatigue syndrome, the use of over-the-counter analgestic medication often helps to alleviate symptoms. Many of the symptoms associated with over-training will not improve with the use of medication. TREATING OVERTRAINING If full-blown overtraining syndrome has developed, complete rest for 6-12 weeks is essential (Noakes, 2003). Continuing to train and race will just exacerbate the condition and result in poor performance, increased risk of injury, and infection. Continuing to train will also just prolong the period of time that the athlete will ultimately have to rest (Noakes, 2003). When coming back from overtraining syndrome, it is important to do so slowly. Athletes need to learn how to match their mental desires with the ability of their bodies so that they do not repeatedly demand more of their bodies than they can deliver (Noakes, 2003). PREVENTING OVERTRAINING One of the most important factors for preventing overtraining is to gain an under-standing of the stages of overtraining and have the self-awareness to differentiate between overtraining and the more generalized fatigue that is a natural part of training. For Brendan Foster (a British distance runner who founded the Great North Run), one of the signs of overtraining is when you "wake up tired and go to bed even more tired" (Noakes, 2003). When diagnosing overtraining syndrome, it is important to determine when the fatigue being experienced is excessive. One method that is commonly used by athletes to monitor their fatigue level and compare them to previous years is to keep a training journal. Recording and analyzing training and racing performances allows the athlete to detect symptoms of overtraining (Noakes, 2003). DEBATING ABOUT OVERTRAINING Researchers have not been able to determine the exact physiological changes that cause overtraining, which has led some experts to argue that overtraining is completely mental. However, Noakes (2003) argues that when physically stretched, the body, not the mind, is always the first to quit. Many overtrained runners find that while their mind is ready to run, their body is exhausted. I presented this topic in my K533 Advanced Theories of High Level Performance class at Indiana University. At the end of the presentation, one student argued that overtraining is not a real condition, but simply athletes becoming wimps who are unable to handle the training load placed on them. Each athlete has a different range of physical abilities, but they also differ in the ability to withstand fatigue. Noakes et al. (2005) propose that fatigue is a result of a central governor aimed at maintaining homeostasis throughout the body.   Hard work and dedication are essential ingredients for an athlete to become successful. However, athletes can reach the point where they overdo it and enter into overtraining syndrome. The most common symptoms associated with over-training are fatigue, muscle soreness, difficultly sleeping, and loss of appetite. The only treatment for overtraining is rest. Once an athlete is overtrained, continuing to train just exacerbates the cycle of over-training. While some experts argue that overtraining is not a true syndrome but simply a mental condition, I argue that an athlete's susceptibility to becoming overtrained is influenced by the athlete's central governor. When coaching an elite athlete, it is important to determine what type of training the athlete best responds to, and also to recognize symptoms of overtraining presented by the athlete. LITERATURE CITED Barron, J.L., Noakes, T.D., Levy, W. et al. Hypothalamic Dysfunction in Overtrained Athletes. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology • Metabolism 60(4): 803. Berglund, B., Safstrom, H. (1994). Psychological monitoring and modulation of training load of world-class canoeists. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 26:1036-1040. BrainyQuote. (2013). Hard Work Quotes. Available online at http:11www. brainyquote.comlquotesIkeywordslhard_ work.html Costill, D.L., Flynn, M.G., Kirwan, J.P. et al. (1988). Effects of repeated days of intensified training on muscle glycogen and swimming performance. Med Sci Sports Exercise 20: 249-254. Costill, D.L., King, D.S., Thomas, R. et al. (1985). Effects of reduced training on muscular power in swimmers. Physician and Sports Medicine 13:94-101. Counsilman, I.E. (1968). The Science of Swimming. United States: Prentice-Hall. Dressendotfer, R.H., Wade, C.E., Scaff J.H. (1985). Increased morning heart rate in runners: a valid sign of overtraining. Phys Sports Med 13:77-86. Foster C, Lehmann M (1997) Overtraining syndrome. In: Guten GN (ed) Running injuries. Saunders Philadelphia:173-188 Heiss, R.C. (1971). Unfallverhutung beim Sport. Schomdofi Karl Hoffman Ho-Yen, D.O. (1990). Patient management of post-viral fatigue syndrome. British Journal of General Practice 40(330): 37-39. MacConnie, S.E., Barkan, A., Lampman, R.M. et al. (1986). Decreased hypothalamic gondadotropin-releasing hormone secretion in male marathon runners. The New England Journal of Medicine 315(7):411-417. McKinzie, R.T. (1923). Exercise in Education and Medicine. Saunders, London. Mayo Clinic. (2013). Hyperthyroidism. Available online at http:11www.mayoclinic.comlhealthlhyperthyroidismIDS00344. Newton, A.F.H. (1947). Commonsense Athletics. Berridge, London. Noakes, T. (2003). Lore of Running. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Noakes, T.D., Gibson, A.S.C., Lambert, E.V. (2005). From catastrophe to complexity: a novel model of integrative central neural regulation of effort and fatigue during exercise in humans: summary and conclusions. British Journal of Sports Medicine 39: 120-124. Sjostrom, M, Friden, J., Ekblom, B. (1987). Endurnace, what is it? Muscle morphology after an extremely long distance run. Acta Physiologica 130(3): 513-520. Waitz, G., Averbuch, G. (1986). World class: A champion runner reveals what makes her run, with advice and inspiration for all athletes. New York, NY Warner Books. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Molly Hirt is a graduate of Bloomington North High School (IN), and the University of Notre Dame, where she was an outstanding Middle Distance and XC runner. She studied under Dr. Phil Henson while pursuing a Masters' Degree in Applied Sport Science at Indiana University. Dr. Henson Ph.D. served as faculty advisor on this article. |

STAGES OF OVERTRAINING

STAGES OF OVERTRAINING

Berglund and Safstrom (1994) found that a mood state, which was measured using the Profile of Mood State (POMS) questionnaire, showed that Swedish canoeists preparing for the Olympics deteriorated progressively as the training demand increased (i.e., their POMS scores were abnormally high). When the training was reduced for a taper, all of the athletes by the second week exhibited lower POMS scores. Many athletes who are overtrained demonstrate decreased vigor and increased feeling of fatigue, depression, and anger (Noakes, 2003). These symptoms occur because over-training syndrome appears to be caused by a disruption in the body's ability to respond to normal stresses, such as running. In order to protect the body and maintain homeostasis, the brain is prevented from recruiting muscles used during training, and results in fatigue and infections.

Berglund and Safstrom (1994) found that a mood state, which was measured using the Profile of Mood State (POMS) questionnaire, showed that Swedish canoeists preparing for the Olympics deteriorated progressively as the training demand increased (i.e., their POMS scores were abnormally high). When the training was reduced for a taper, all of the athletes by the second week exhibited lower POMS scores. Many athletes who are overtrained demonstrate decreased vigor and increased feeling of fatigue, depression, and anger (Noakes, 2003). These symptoms occur because over-training syndrome appears to be caused by a disruption in the body's ability to respond to normal stresses, such as running. In order to protect the body and maintain homeostasis, the brain is prevented from recruiting muscles used during training, and results in fatigue and infections.