| Over It: Variables That Affect Take Off |

| By: Stephan Munz

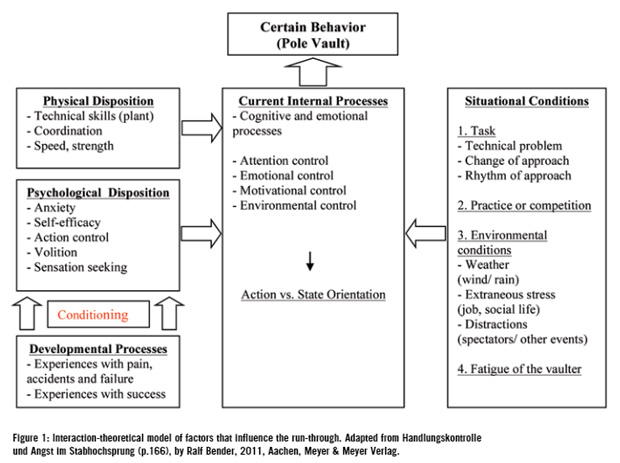

Originally Published in: Techniques Magazine Provided by: USTFCCCA The run-through, an abrupt cessation of motion during the take-off phase, results in the inability of a vaulter to finish the jump. Depending on the degree of the problem, the run-through can affect a vaulter's development for several weeks, months or, in severe cases, it can end the vaulter's career. The first article of this two article series shed light on the underlying psychological principles of running-through. It was the goal of the first article to provide a holistic framework of psychological variables (see Figure 1) that practitioners and coaches can use as an orientation to identify possible problems of running-through behavior. The second article of this series presents practical strategies and applications for coaches and athletes to prevent and fight against running-through. A HOLISTIC MODEL OF THE RUN-THROUGH The first article presented a holistic representation of developmental, psychological, physical and situational variables based on the work of the German researchers Nolting and Paulus (1999), as well as Bender (2011). The three influencing components showed possible impacts on the internal, cognitive and emotional processes of athletes. For instance, the framework shows how developmental processes in the form of negative experiences can have an impact on a pole vaulter's perceptions of anxiety, self-efficacy, action control and volition. The framework also points out that physical dispositions (technical skills, coordination, speed and strength) as well as situational conditions (task at hand, environmental conditions, or current fatigue levels of the vaulter) can have an active impact on current internal thought processes, which can ultimately lead to possible action (no run-through) or state (run-through) orientations. (see Figure 1) As mentioned in the previous article, this framework should serve coaches, practitioners and athletes as a compass to detect possible causes of running-through behavior. The framework should serve as an overview to evaluate running-through so that coaches can draw the right conclusions and intervene with appropriate strategies if running-through occurs. The following section provides possible practical strategies coaches and athletes can use to prevent or fight against occurring phases of running-through. STRATEGIES AND PRINCIPLES Identify the problem. If running-through occurs, it is important to identify the type of the problem first. Running-through is much easier to solve when the type of problem is identified, as the cause leads to selecting the right solution. To achieve this, it is essential that an active and open communication loop between the coach and the athlete exists. Coaches must foster a trusting relationship with their athletes so that their athletes feel comfortable discussing problems, feelings and personal concerns. When it comes to mental or psychological problems, athletes are often times concerned about showing weakness and are not willing to talk openly to their coaches about the problem. Therefore, it is key that behaviors, emotions and thoughts are mutually and causally interdependent between the coach and the athlete (Huber, 2013).

Coaches should control the biomechanics of the run (body posture, stride length, knee lift, recovery), as well as the carrying technique of the pole. Most importantly, an accurate internalization and execution of the three-step plant motion and a correct take-off on the entire foot must be implemented. Possible scenario. Based on personal experience, running-through often times occurs when vaulters utilize a bigger pole in practice or competition. Vaulters may run through although it seems that they hit the correct spot at the take-off mark. It can be the case that they change their approach rhythm due to the rationalization that they believe it is necessary to run harder and faster with the bigger pole. The vaulter starts his approach faster and less controlled, which can result in either a shorter stride length due to an increased cadence or an increased stride length due to a more explosive push-off at the beginning of the approach. Consequently, vaulters are too far away or too close at the mid mark and they have to prolong or shorten the last steps to hit the take-off mark. Longer steps at the end lead to a decrease in speed and a lower body posture. This makes it difficult to "attack" the last three steps and to engage in a proper plant and take-off motion. If the vaulter increases the stride lengths due to a harder push-off at the beginning of the run it is likely that the vaulter ends up being too close at the take-off. As a result, the vaulter loses the correct sight picture and feeling for the approach/plant and runs through. PROBLEMS BASED ON CONDITIONED PAST TRAUMAS Respondent or classical conditioning is an involuntary and unconscious process for learning physiological and emotional responses such as fear or anxiety that can negatively affect the execution of movements (Huber, 2013). I believe that in the pole vault, the cause of the problem is often times the conditioning process of a negative stimulus such as an accident or a pole break. The vaulter pairs a neutral stimulus such as a pole, the pit or the pole vault movement with the negative stimulus of the accident. The presentation of the neutral stimulus elicits fear and anxiety. In my experience, vaulters often times report that they want to perform but simply can't get their body to do it. Coaches can use the following strategies to initiate a deconditioning process. Confront past trauma. If an accident or pole break occurs, it is likely that athletes will tend to suppress these traumatic experiences. Oftentimes, they ignore them as if they have never happened. However, these experiences can lead to an unconscious conditioning process that will result in fear and anxiety. It is essential for athletes to have an open discussion about these past experiences. Athletes should confront past traumas and put them into perspective as an objective reality. They will recognize how these experiences contributed to their debilitating physiological response and current problem. For example, it can help if athletes talk or even watch a video of a jump where they missed the pit. The release of negative emotions and feelings can be assuaging and the athletes can put the past trauma into perspective. The athletes can become aware of their skills and competence again (Huber, 2013). An injury or trauma history report can also help to reveal underlying emotional events from the past that could trigger blocks and performance anxiety. In their book "This is your Brain on Sports," David Grand and Alan Goldberg (2011) point out the importance of these reports. The reports uncover the roots of the problems based on every trauma and injury that the athletes have experienced in the past. Even minor injuries that are unconsciously stored in the athlete's nervous system can affect the execution of motions. History reports can help to understand the problem and individualize further treatments (Grand & Goldberg, 2011). In severe cases traumas require professional interventions. Use cognitive restructuring. Cognitive restructuring is the process of reflecting about thoughts and emotions that result from the consequences of a negative experience. While thinking and reflecting about the emotional responses, the athlete attempts to change negative thoughts or false beliefs. For instance, there is no reason for vaulters to believe that they cannot successfully jump anymore after one missed jump or crash. Vaulters must be encouraged to establish an objective perspective and point of view ("I have had thousands of successful jumps and this one missed jump will not change anything"). It can also help vaulters to create a list of why they should be able to successfully execute the jump. It must be clear that there are many more reasons for a vaulter to have successful jumps than there are for not taking-off. Furthermore, it can also be a good strategy for the coach and the vaulter to create a plan of attack: a counteroffensive of how to beat running-through. The coach and athlete establish rules, guidelines, strategies, as well as short- and long-term goals of how they can overcome running-through. The coach must have an open ear and be amenable to the strategies and ideas of the vaulter to fulfill his or her needs (Huber, 2013). Use self-talk. Using positive self-talk can help to change thoughts, emotions and physiological responses (Conroy & Metzler, 2004). It can help to recapture optimism, which in turn can create positive emotions and a more relaxed body state. Particularly right before the vaulter starts the approach, positive self-talk can help to protect the intention of taking-off from disturbing variables (Huber, 2013). Short, powerful and positive statements should be used. This can also be a motto or battle cry that can be developed in meetings with the coach. Mottos, lyrics or battle cries from movies, songs, or other sport stars who have had to overcome obstacles or difficult situations can be helpful. In addition to positive emotions, self-talk can also create a healthy relationship to counteract negative emotions that a vaulter experiences. The athlete should be aware of the fact that negative thoughts or anxiety often times serve as a natural defense system of the body (Some movement patterns of the pole vault go against the safety needs of the human body). Therefore, it is important that athletes accept them and perceive them as something natural. This relationship and perception of negative emotions can help a vaulter to be more relaxed when perceptions of anxiety or nervousness appear (Weinberg & Gould, 2011). Use muscle relaxation to release stress and anxiety. Based on personal experience, vaulters' muscles tighten up due to anxiety or stress before they begin their approach. This increased muscle tension can lead to uneconomical contraction and relaxation phases of the muscle system, a decrease in performance and a reduced body perception. This, in addition to feelings of anxiety and stress, can worsen the run-through behavior and the performance of the vaulter. Progressive muscle relaxation can help to relax the muscular system and release stress. If vaulters are tensing up before a competition or vault session, they can use the following techniques to relax. The following program is based on Edmund Jacobson's progressive relaxation technique (1938). It is a keystone for modern relaxation procedures. Getting ready. The vaulter should find a quiet, comfortable place to sit. She closes her eyes and lets her body go loose. The vaulter takes about five diaphragmatic deep and slow breaths before he or she begins. Breathing through the chest triggers left brain domination and activation which increases muscle tension and should therefore be avoided. Diaphragmatic breathing increases the amount of oxygen taken into the blood stream and enhances right brain activity, which can be beneficial for the execution of motor behavior (Garfield, 1984). Tense: The vaulter applies muscle tension to a specific part of the body. The vaulter focuses on the muscle group that is tensing up. She takes a slow, deep breath and contracts the muscles as hard as possible for about five seconds. Other muscle groups should remain relaxed. Relaxing the tense muscles: After about five seconds, the vaulter quickly relaxes the contracted muscle. The tightness will flow out of the tensed muscle. The vaulter exhales as he engages in this step. It is important to feel the difference between the tension of the contraction and the relaxation. The vaulter remains in this relaxed state for about 15 seconds. He or she can repeat the cycle for the same muscle or move on to the next muscle group (AnxietyBC, 2014). The exercise should be applied the day or several hours before the competition if muscle tension occurs. In their book "Foundations of Sport and Exercise Psychology" Robert Weinberg and Daniel Gould (2011) offer further instructions and guidelines of how progressive muscle relaxation techniques can be implemented.

Use mental imagery with gradual stimulus presentation. If a vaulter suffers from running-through and feels anxiety before the jump, mental imagery can help to relax and reduce anxiety. A gradual stimulus presentation is key. Gradual stimulus presentation is the bit-by-bit introduction of the conditioned stimulus. The process starts with the vaulter imagining and thinking about a simple jagodin (taking off without finishing the swing) from a short approach. Vaulters repeat the jump over and over again in their mind from the first and third person perspective. If vaulters are able to imagine the jump in their minds from a short approach without feeling stressed or anxious they can go on and add other components to the imagination (longer approach, swing, etc.). They can also mentally simulate the use of a bigger pole in different competition or practice situations. Furthermore, imagery can also serve as training activity to facilitate the learning process of technical skills. It can be implemented before or after vaulting sessions, video sessions, or at the end of recovery sessions such as yoga or stability circuits. Garfield (1984) provides a nice introduction of how mental rehearsal and imagery can be implemented in daily practice sessions. After the vaulter has regained confidence with mental imagery, gradual stimulus presentation should also be applied during the actual execution of the motion. If severe running-through behavior is prevalent, it makes sense to introduce or relearn the jump and pole vault movement in different environments first. Introduce playful exercises with the pole in different scenarios and environments other than the pole vault pit. Under water pole vault, jumping from boxes with the pole, simulating the pole vault movement on a rope and jumping into a sand pit with a pole can help the vaulter to re-experience the vault in a safe and non-competitive environment. The conditioned stimuli must be presented in a joyful and playful way without pressure or feelings of anxiety. The principle of generalization can help the vaulter to relearn the pole vault movement. Generalization occurs when a previously learned response is transferred to a different, but somewhat similar situation. In other words, if a new stimulus from a new exercise is presented, the individuals can react to it as if it was the old stimulus that they already encountered (Huber, 2013). For example, if vaulters can execute the takeoff movement to catch a rope and execute the swing, they already feel more confident and familiar with the situation if they have to do the same movement with a pole. This principle can be extremely helpful to build one exercise on another after severe running-through periods. During this transfer process of exercises the vaulter must also experience fun and a relaxed atmosphere. Short games and challenges can also be introduced. The pole vault experience should be joyful again. Once this experience has been re-developed, the athlete can return to the pit and begin to vault again. Slowly increase the complexity of pole vault specific exercises at the pit. Develop the pole vault as a step-by-step process based on exercises that do not overload the athlete. A vaulter can regain confidence at the pit again by executing basic exercises over and over again without feelings of anxiety or stress. This means that after severe phases of running-through, one has to start from scratch again. Straight pole work from two, three or four steps can be a good starting point. It is important to add one component at a time. Furthermore, time and patience are the most important factors. Often times the vaulter jumps from a longer approach too soon. This can lead to a new phase of running-through due to the fact that the execution of the movement is not stable and automated enough. The vaulter cannot protect the execution if other unexpected variables come into play. As a result, these basic drills must be a part of every practice for a long period of time. If running-through occurs again, the vaulter has to simplify the exercise and regain confidence and comfort from easier exercises from a shorter approach with a smaller pole. To support that step, it is essential that the coach eliminates as many extraneous variables as possible. Eliminate extraneous and disturbing variables. If a vaulter suffers from running-through, it is important that the coach oversees and regulates the extraneous and situational variables during practice and re-training. Breaking down feedback. It is essential that coaches provide only a limited amount of information at a time. Coaches should not overload the athlete with tips and explanations. As discussed in the previous section, the athlete needs a great amount of cognitive capacity to protect the intention of the movement. The coach should not provide extensive detailed information at once. In phases of running-through, the athlete should only focus on one aspect at a time. In her book "Attention and Motor Skill Learning" Wulf (2007) supports this thesis by pointing out that reducing the complexity of feedback can also enhance motor learning processes. Wulf (2007) also shows that directing attention to movement effects (desired outcome of movement) results in superior performance than focusing on the actual coordination of the body movements. Technical training: During phases of running-through, focus on technical improvements as opposed to attempting to jump high. Use smaller poles and shorter approaches. It is about gaining confidence back and developing a rhythm and automaticity. This can be accomplished more easily if the athlete is not at the limit in terms of grip, pole size and approach length. Weather. Wind, rain and temperature can influence and affect the vaulter's performance and confidence. Although, it is very important for every vaulter to jump under difficult conditions to gain more experience and toughness, a vaulter who is going through a run-through phase should avoid this additional stress. If possible, vaulters should jump inside for a couple of sessions so that they only have to focus on the pure execution of the movement, instead of having to make additional adaptations to extraneous variables. Individual practice sessions. During running-through phases, it can be helpful if the coach implements individual practice sessions with the athlete. Athletes can better focus on their individual problem without worrying about disturbing noises and actions. The coach can implement a more professional atmosphere where vaulters can completely focus and concentrate on their actions and behaviors. In addition to that, the coach should make sure that other disturbing variables such as music or other noises are eliminated as well. Less is more. Make sure that the athlete does not take too many jumps. If vaulters become tired and fatigued, it is much more likely that they are going to run through again at the end of practice. This can destroy a productive period of not running-through and they lose confidence. Furthermore, it is important that athletes are physically fit and fresh. It can be helpful to implement a rest day before the vault practice so that athletes are physically and mentally well rested before they jump. LIMITATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS Ultimately, creating a holistic model of the variables that influence and affect the run-through is extremely difficult due to the complexity of the problem. The pole vault is a physically and psychologically challenging event where many factors and variables can come into play. This article primarily focused on the psychological factors that can play a role in running-through. It must be made clear that there are other underlying theories and variables that, by necessity, were excluded in this article. For instance, theories about motor learning and motor control behavior can give additional insight in terms of the execution and control of movements. Studies about eye-hand coordination or the estimation of distances could provide further explanations of run-through behavior. Furthermore, biomechanical analyses of the approach, plant and take-off may also describe why certain vaulters are more likely to run-through, due to a less effective execution of specific movements. Many of the presented strategies and guidelines focus on the scenario of a vaulter who suffers from conditioned past traumas. It may be possible to build on these ideas through specific principles and lessons of how a coach could foster the self-efficacy of a vaulter in specific situations. Furthermore, additional strategies of how the volitional control can be enhanced could also be beneficial for some vaulters with running-through problems. Further studies about attention control and concentration processes that can protect the intention from disturbing variables are likely the most relevant. In regards to anxiety, the principles and guidelines could also be extended to include somatic anxiety reduction techniques, cognitive anxiety reduction techniques, and multimodal anxiety reduction techniques (Weinberg & Gould, 2011). As a final result one can say that the developed model in Figure 1 shows some of the first steps of how different variables and factors can influence the behavior of a pole vaulter. This model can serve as a map to coaches where they can locate the origin of their athlete's problem if running-through occurs. Correctly identifying the problem will result in more appropriate interventions and solution processes. REFFRENCES AnxietyBC, How to do progressive muscle relaxation . (2014, January 1). Retrieved May 1, 2016, from http:11www.anxietybc.coml sitesIdefaultlfilesIMuscleRelaxation.pdf Bender, R. (2011). Handlungskontrolle und Angst im Stabhochsprung. Aachen: Meyer & Meyer Verlag. Conroy, D.E., & Metzler, J.N. (2004). Patterns of self-talk associated with different forms of competitive anxiety. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 26, 69-89. Garfield, C., & Bennett, H. (1984). Peak performance: Mental training techniques of the world's greatest athletes. Los Angeles: J.P. Tarcher Grand, D., & Goldberg A.S. (2011). This is your brain on sports: Beating blocks, slumps and performance anxiety for good! Indianapolis: Dog Ear Publishing. Huber, J. (2013). Applying Educational Psychology in Coaching Athletes. Champaign: Human Kinetics. Jacobson, E. (1938). Progressive relaxation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Nolting H., & Paulus, P. (1999). Psychologie lernen Weinheim : Beltz . Weinberg R. S., & Gould, D. (2011). Foundations of Sport and Exercise Psychology. Champaign : Human Kinetics. Wulf G. (2007). Attention and motor skill learning. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Stephan Munz is a Ph.D., candidate in Educational Psychology at Virginia Tech. As a student, Stephan focuses his research on theories of motivation both in the classroom and how they affect peak performance environments in coaching and athletics. Stephan received his undergraduate degree in sports science and biomechanics from the University of Stuttgart (Germany) and his master's in Educational Psychology at Virginia Tech where he was also a member of the pole vault team. Stephan currently serves as a volunteer assistant coach in the pole vault. |