|

A Practical Guide to Speed and Speed Development By: Mike Thorson Originally Published in: Techniques Magazine Provided by: USTFCCCA

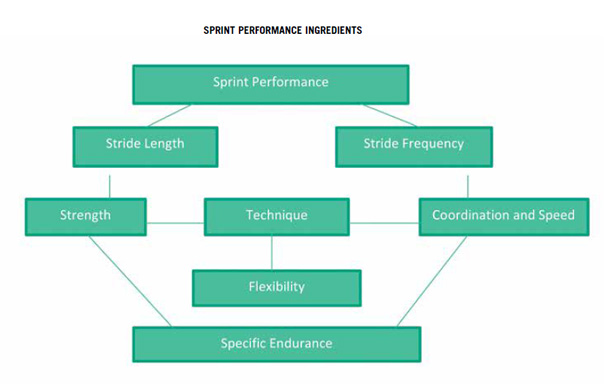

Speed: Stride length multiplied by stride frequency. It is defined as the ability to perform specific movement in the shortest possible time. Velocity: The rate of change of motion in a given direction. GOAL (MISSION STATEMENT) SPEED CAN BE SIGNIFICANTLY IMPROVED THROUGH A SYSTEMATIC TRAINING PROGRAM Speed development is defined as runs of 95-100% intensity over 30-60 meters, or up to six seconds of running at maximum effort. Speed is the product of two very basic parameters: stride length (SL) and stride frequency (SF). Of the two, SF, which is measured in single strides per second, is the

Speed improvement results from training at continuous high, varying intensities! Speed training must be done at maximum speeds with many repetitions to train the correct motor patterns. Skill development (sprint mechanics) must be pre-learned, rehearsed and perfected before it can be done at high speeds. Flexibility must be developed and maintained on a daily basis. An athlete's strength development must be parallel with developments and increases in speed. (Functional strength = SPEED).

MAXIMUM VELOCITY TRAINING: STRENGTH: SPEED ENDURANCE: ACCELERATION:

RECOVERY/REGENERATION: BREATHING PATTERNS: MARAUDER SPEED PRINCIPLES

Acceleration (defined) the rate of change in velocity. It allows the sprinter to reach maximum speed in an efficient, minimum amount of time. Most sprinters reach maximum speed between 30-60 meters. Very seldom in team sports do athletes go beyond the acceleration phase. They are constantly stopping, starting and changing directions. MECHANICS OF ACCELERATION Posture: The alignment of the body is critical, with posture being dynamic-constantly changing with every step. Remember the so-called lean comes from the ankle and not the waist. Arm Action: The arms assist to produce force and aid in balance so that forces can be applied toward the ground. Arms/Charlie Francis: All sprinting is controlled by the arms according to legendary Canadian sprint coach who is now deceased, Charlie Francis. When neurological pattern was researched it revealed that the arms do precede the legs and the faster the arms move, the faster the legs will in return. Leg Action: The emphasis is on the backside mechanics-the legs are pushing back behind the body during the first steps/strides. The pushing action begins in the first 4-6 steps, after which a sprinter is attempting to get into the "hips tall" sprint position. Acceleration Pattern: It is necessary in order to obtain the correct force application and proper transition to top speed to have the proper acceleration pattern. The pattern typically sees each step increasing until full speed is achieved. Many athletes take steps that are too long, hoping to achieve top speed quicker. Typically this causes just the opposite effect. Force Application: The goal in applying force is to create a positive shin angle so that the foot initially contacts the ground behind the center of gravity. Quite often the opposite occurs, thus a braking action when the foot gets out ahead of the center of gravity and causes a braking action. A coaching cue is to have the sprinter get the foot down as quickly as possible-you can only apply force if the foot is on the ground. Acceleration Training: Improvement in acceleration is closely linked to gains in power. Gains in power will result in the ability to produce higher amounts of force more quickly, thus decreasing ground contact time. Power (defined) is the rate at which work is done. Work divided by time = Power. Acceleration Breathing Pattern: The athlete will typically hold breath (the in if you are working in and out breathing) during the acceleration phase before breathing out during the transition to the maximum velocity phase. Acceleration Drills: There is no substitute for the real thing. Therefore, the best way to train acceleration is to do just that and do not deviate very much from true acceleration work (drills). An example of acceleration work just using the body would be simple falling starts. DRILLS

BALANCE Balance may be the most neglected component in training. Yet, it is the most important component in athletic training because it underlies all movement. It is a very simple task, but is highly complex when it comes to sprinting. Balance does not work in isolation when it comes to athletics. Things such as coordination and agility depend on a well-developed sense of balance. The ability for the sprinter to produce force at the right time, in the right plane, and in the right direction, is highly dependent on balance. Balance and actually sprinting and running involve the body repeatedly losing and regaining control of its center of gravity because a runner (sprinter) is always moving. Balance can be improved through a variety of different sensory exercises. A mini tramp, K-board, foam blocks or other means of equipment can certainly be used to train balance. But always remember the best equipment is the body itself. Examples of balance training activities:

**Nearly any type of dynamic warmup drill can be used as balance training by merely having the athlete close eyes. Athletes will discover an entirely new sensory experience when drilling with eyes closed. WARMUP The warmup prepares the body for the training session, both from a Different types of Warmup:

SPRINT MECHANICS A sprinter is only as fast as their mechanics will allow! The principal mechanic keys/points:

Problems associated with excessive backside actions:

SPRINT MECHANIC TEACHING CUES

SPEED DEVELOPMENT EXERCISES/ WORKOUTS/SAMPLES Maximum Velocity Training

Speed Endurance

Acceleration Training

Resistance Training

Assisted Training

**The 10% rule should be in effect for both assisted and resistance training. No more than 10% of the athlete's body weight should be used when providing overload for resistance. And the time should not be slowed by 10%. The same is true of assisted training: the athlete should not increase speed by more than 10%. CONTRAST TRAINING This is one of the best ways to develop pure acceleration and maximum speed. It involves combining resistance training and assisted running followed by the actual race model run ("the real thing" over acceleration or velocity distances). POOL TRAINING Pool and hydro therapy has long been used for rehabilitation. It also can be used for recovery and become a part of regular training programs. The pool can be used for strength gain improvement, skill development and flexibility employing deep water intervals and regular swimming. MENTAL/PSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS One of the trademarks of successful

OBJECTIVE The objective of this sprint article is to provide a practical and simple guide to speed and speed development. It is our goal that we can provide both coaches and athletes alike a basic, yet some-what technical understanding of speed and what is required to develop and enhance it. REFERENCES 1. Francis, Charlie, The Charlie Francis Training System E-book 2. Gambetta, Vern , Gambetta Method, 2nd Edition, 2002 3. McFarlane, Brent, The Science of Hurdling and Speed, 4th Edition, Canadian Track and Field association, 2000 4. Pfau, Dan, Conversations, Handouts, Clinic 5. Seagrave, Loren, Speed Dynamics, Conversations, Handouts, Clinics 6. Winckler, Gary, University of Illinois, Handouts, Clinics, Conversations. -------------------------------------------------------------------- Mike Thorson has been an assistant coach at the University of Mary in Bismarck ND in charge of the hurdles since 2017 after spending the previous 24 years as the director of track and field/cross country at the school. |

The Marauder Speed program is based on four key concepts: most important. The Speed Equation: Stride Frequency X Stride Length = SPEED. That equation, however, means very little to your typical sprinter. In layman's terms: The goal of the sprinter is to put big forces into the ground in a short time. The longer an athlete is on the ground the greater the loss of stride frequency.

The Marauder Speed program is based on four key concepts: most important. The Speed Equation: Stride Frequency X Stride Length = SPEED. That equation, however, means very little to your typical sprinter. In layman's terms: The goal of the sprinter is to put big forces into the ground in a short time. The longer an athlete is on the ground the greater the loss of stride frequency.