| Development Rates: A Comparison for Elite Performers in the Throwing Events |

| By: Don Babbitt, University of Georgia

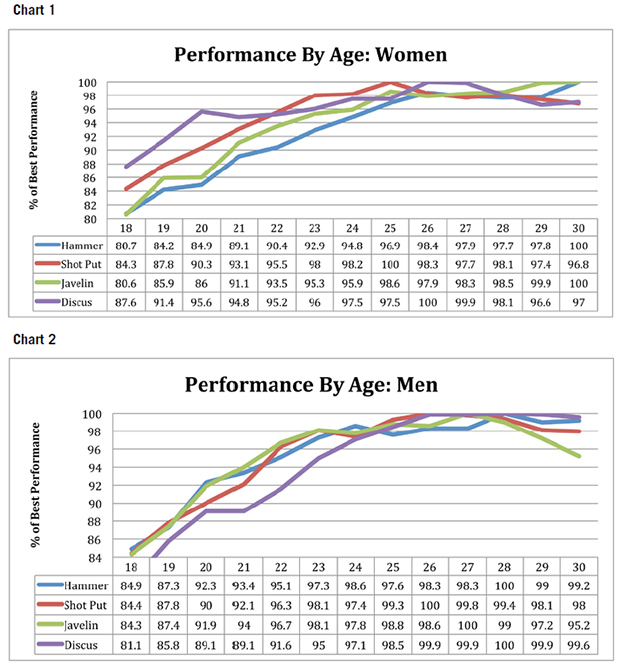

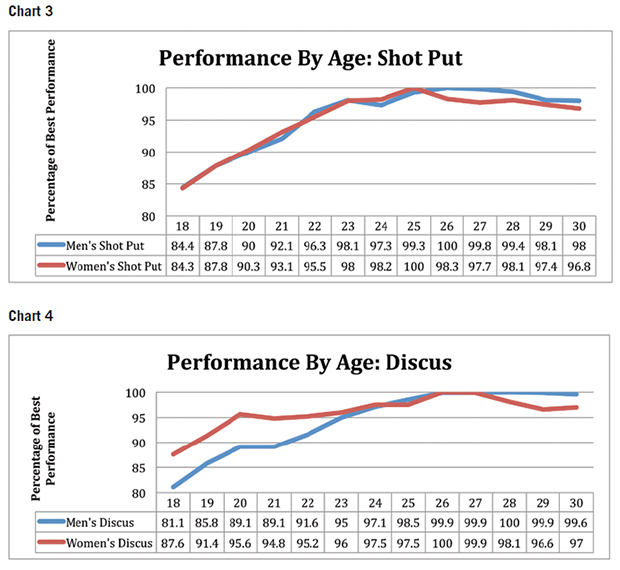

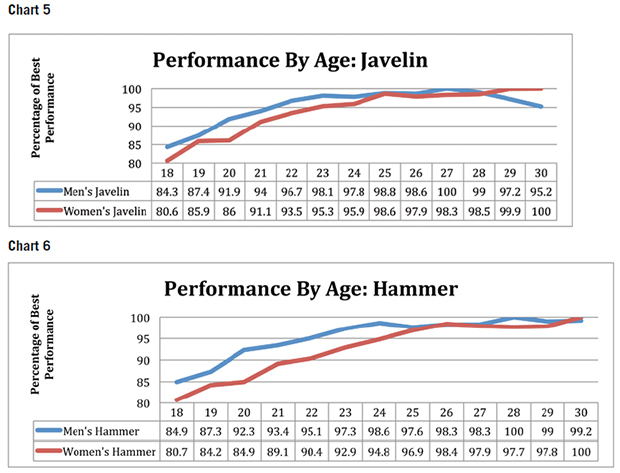

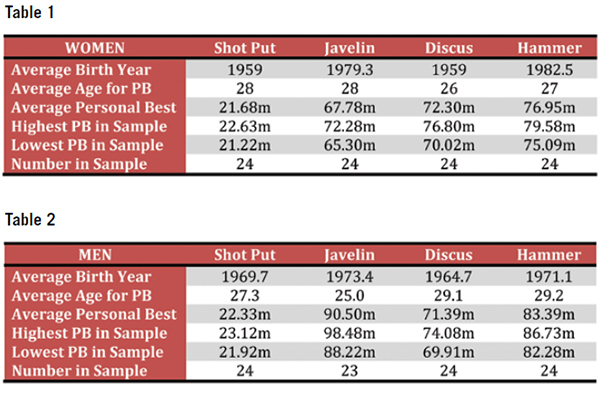

Originally Published in Techniques Magazine Provided by: USTFCCCA This study is an extension of a previously published article by Babbitt and Saatara (1), which concentrated solely on the development rates of male throwers. These analyses were performed in an effort to determine how long it will take to reach the highest level of performance in each of the four throwing events, which in turn should help coaches and athletes set realistic goals and timetables for future athletic development. Development rates between the four throwing disciplines will also be examined for female throwers and a comparison between both genders in all four throwing disciplines will be carried out to determine any developmental differentiation among elite level performers. METHODS Performance data for the top 24 throwers of all-time for each gender (there were only 23 for the men's javelin) in the four throwing disciplines (hammer, shot put, discus and javelin) was analyzed to determine the following values: 1. Average age at when the top performance was achieved for each gender in each event group. It should be noted that the percentage of the group's best performance as a whole, in a given year, can be different from the average age in which the personal best was achieved for the group. To determine the percentage of a group's overall performance, the average distance for all twenty-four throwers was averaged for each year at each age between the ages of 18 to 30. The age with the highest average performance of the group was assigned the value of 100 percent. The averages for the remaining ages were then divided by the average for the best year to yield a percentage that less than 100 percent. RESULTS Tables 1 & 2 lists the average birth year, age, age of personal best (PB) and the high and low PB for each for each gender of each throwing event group. Large differences in birth year were observed between the genders for both shot put and discus groups. The men's shot put group had an average birth year of 1969 compared with an average birth year of 1959 women's shot group. The gap in birth year between the discus groups was smaller, in that it was just under a six-year difference (1964.7 for men versus 1959 for women). There were moderate differences between the genders of both the hammer and javelin groups, with a difference of six years(1973.4 to 1979.3) observed between the genders in the javelin and an eleven-year difference (1971.1 to 1982.5) between the genders in the hammer. These differences were most likely due to the addition of the women's hammer as an official event at the Championship level in 1999, and the IAAF rule change in the women's javelin in 1999. These circumstances tend to skew the women's top performance group toward a much younger age. The average age for personal best (PB) performance was found to be very similar for the shot put groups. Conversely, there were larger differences in the other three throwing groups. Both the discus (29.1 to 26 years of age) and hammer (29.2 to 27 years of age) groups revealed an older average age for personal best achievement for the men's group. The javelin groups showed the opposite finding, in which the women's group had an average age of PB that was three years older than that of the men's group (28 to 25 years of age).  Conversely, the development progression for the discus is one of the quickest for the women, whereas it shows the slowest rate of development for the men. A quick comparison of Charts 1 and 2 reveal that at young ages (18-21), the women's discus performance level is much better than all the other throwing disciplines. The developmental progressions for both the javelin and hammer appear to be similar for both genders; however, the average age of best performance is older for the women's top performers by two to three years. See Chart 1 & 2  The rate of ascension toward top performance for the javelin was greater for the top male throwers when compared to top female throwers (see Chart 5). The javelin also revealed the largest age difference between the genders in terms of age of top performance. The men's group reaching their top performance at age 27 while the women did not reach their top performance until age 30. The rates of development for the hammer the was similar in nature to that of the javelin in that the men showed a faster rate of performance development than the women up to age 26 (see Chart 6). The men also reached their peak performance a little earlier than the women (28 years of age to 30 years of age) DISCUSSION In comparing gender differences between the rate and age to top performance of the world's elite throwers, the shot put was seen to be the most similar. Of the four throwing disciplines, this event requires the most power development and has the highest percentage of release velocity generated in the final delivery phase (2,6). This suggests that throwers with superior power generating capabilities will have a greater advantage in shot putting when compared with the other throwing events. With this being said, the rate of strength development, rather than technical development, could be the primary determinant to improving performance up to peak levels. Training methods for power development, such as Olympic and Power lifting, plyometrics and sprinting, are employed by both genders (4). These programs are often very similar and could explain the parallel slopes of performance development for this particular discipline. In addition, it appears that the development of power could be even more influential in the women's shot put, given the 4kg shot is lighter in comparison to strength levels of top level female shot putters, when compared with those of men to the 7.26kg shot. This may explain why the age of peak shot put performance for the elite women's group was younger (25 years of age), when compared with the men (26 years of age). The developmental rates between genders for the discus throw were in stark contrast to that of the shot put. The women were roughly five percentage points ahead of the men between ages 18 to 23 as they trended toward their collective age of top performance. After age 23, the level of performance was very similar for both genders up through the age of 30. Reasons as to why women tended to increase performance at a faster rate for the "developmental years" could be due to differences in power development, and the fact that the women's competition implement is only half the weight of the men's implement (lkg to 2kg), while the strength and power levels of elite women are at least 60-70 percent of that of elite men. Women's discus throwers in this elite group appeared to rely on power development for performance compared with the men's elite discus group. Because power development can also be enhanced at a much faster rate than speed and skill development, this hints to the notion on performances that rely of power will develop more rapidly than performance in sports that require slower developing skills such as rhythm and timing for success. In addition, it should

be noted that all 24 of the top women's discus throwers of all-time came from the USSR, East Germany, Cuba, China and other Eastern European countries. All of which were heavily influenced by Soviet and East German systems of training, which selected for and emphasized powerful women's discus throwers. This also explains why the average birth year for this group was 1959 which saw these athletes reach their peak in the mid-1970's when the Soviet Union and Eastern European countries were the dominant forces in the women's shot put and discus. It should also be noted that the systems that produced these results are not able to be replicated in today's world of throwing. Because of this, the data for the women's shot put and discus may not provide the exact template of what one would expect from throwers today. In contrast to what we have seen in the developmental rates for the shot put and discus, the javelin and hammer

throw developmental rates revealed both a slower and steadier rate of progression for the women compared to what was seen for the men. For both of these events, the peak age of performance for the elite female throwers was thirty years of age, compared with the peak ages for the men's javelin group of 27 years, and 28 years for the hammer. What made this result even more interesting was the relatively young female athlete sample (average birth year 1979 for javelin) due to an IAAF rule change in the javelin, and the introduction of the women's hammer as an official event in 1999 (average birth year of 1982). One would think that the newness of the events would cause the top throwers to be young, rather than older, but this was not the case. To explain the age of peak performance gap between men and women in the javelin, it can be theorized that it takes longer for women to develop the special strength required for peak performance when compared with men. It may take longer for women to "catch up" in terms of the upper body development needed for the specific demands of the javelin which causes us to see the continued improvement of performances up to and through 30 years of age for this elite group of women's throwers (3, 7, 8). The opposite may be true for explaining the development of women's hammer throwing, relative to the men. This theory is similar to the one proposed to explain the slower development of the men's discus relative to women's discus. In this case, more time may be needed for the women's hammer throwers to develop the ideal rhythm and timing to produce peak performances. The weight of the women's hammer is only 4kg, compared to 7.26kg for the men, and the ball path from the start of the throw to delivery can be in excess of 60 meters (5), therefore, refinement of rhythm and timing may become a more important factor for long throws than that of sheer power application and development.

CONCLUSION This study is the first of its kind to inspect the differences in developmental rates between genders for the throwing events in track and field. It is hoped that the discussion of the data will give coaches an idea of the differences they may expect to see in training athletes of each gender and help them adjust and set their expectations if needed while developing their throwers. Because of the ever-changing nature of the sports of track and field, it would seem that further study using only subject groups made up of the top throwers who have finished their careers within the past 10 years would be the next area scrutinize. REFERENCES Babbitt, D., Saatara, M (2014) Elite-level development rates and age-based performance patterns for the men's throwing events. New Studies in Athletics, 29:3 69-75. Babbitt, D. (2014) Pound for pound; weight lifting and the men's throwing events, Techniques, May 7(4), 6-18. Halverson, L. E., Robertson, M A., Langendorfer, S. (1982) Development of the overarm throw: Movement and ball velocity changes by seventh grade. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 53:3 198-205 Judge, L., Bellar, D., Thrasher, A., Simon, L., Hindawi, 0., Wanless, E. (2013) A pilot study exploring the quadratic nature of the relationship of strength to performance among shot putters. International Journal of Exercise Science, 6(2) 171-179. Isele, R., Nixdorf, E., (2010) Biomechanical analysis of the hammer throw at the 2009 IAAF world championships in athletics. New Studies in Athletics, 25:3/4 37-60. Luhtanen, P., Blomquist, M., Vanttinen, T. (1997) A comparison of two elite shot putters using the rotational shot put technique. New Studies in Athletics,12:4 25-33. Nelson, K R., Thomas, J. R., Nelson, J. K, (1991) Longitudinal change in throwing performance: Gender differences. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 62:1 105-108 Thomas, J. R., Michael, D., Gallagher, J. D. (1994) Effects of training on gender differences in overhand throwing: A brief quantitative literature analysis. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 65:1 67-71 0 Don Babbitt is the Associate Head Coach at the University of Georgia. Don has coached the throwing events at UGA for nearly 20 years and is a regular contributor to techniques. |