|

By: Tatiana Zhuravleva Biomechanical Review By: Jesus Dapena Originally Published in: Techniques Magazine Provided by: USTFCCCA

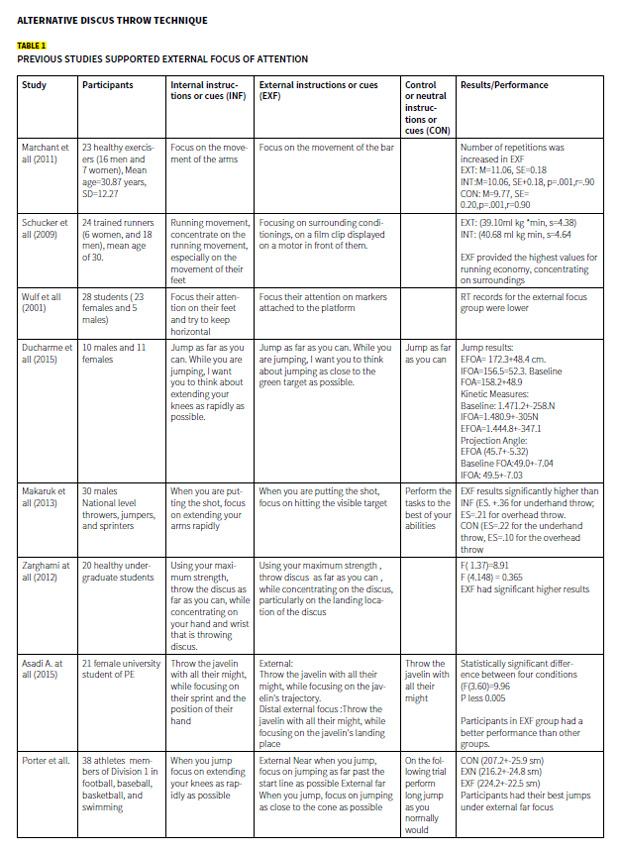

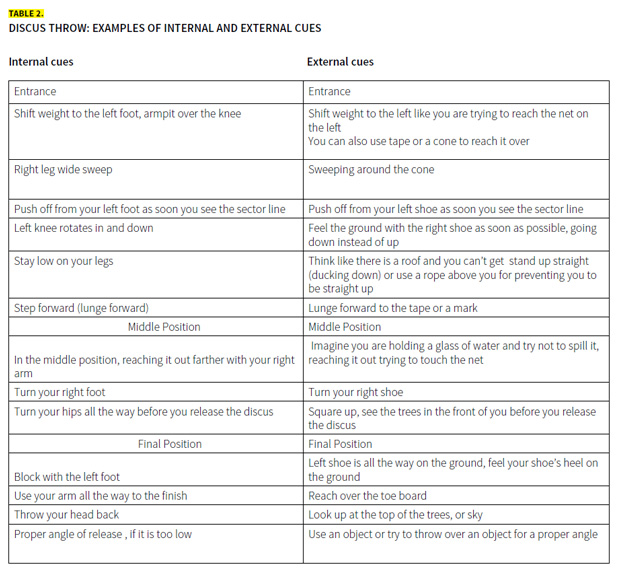

Motor learning is under the umbrella of kinesiology. Motor learning can be found in biomechanics, physiology, psychology, and behavior. The main idea of motor learning is to make people skilled in their area of interest; for example, in sports such as basketball, track and field, baseball, football and many others. Motor learning includes augmented feedback, contextual interference, and focus of attention. According to Magil (2007), attention is associated with consciousness, awareness, and cognitive effort as they relate to the performance of skills. Motor learning focuses more on practice conditions. For example, an indoor track has a different environment than an outdoor track (weather, wind, nose, etc.). The last one is observed changes in coordination dynamics, which makes behavior more consistent even in different environments. Motor learning is a set of processes associated with practice or experience leading to relatively permanent changes to the capability for movement. Individuals cannot learn without different experience. Motor learning research has investigated that using external focus of attention would result in a better performance and learning than internal focus of attention. Track and field athletes depend on instructions and feedback from their coaches during practice and competition. Most of the times, athletes focus on things that they worked on during practice and apply it at the competition. Track and field is a very technical sport, where coaches provide feedback and instructions continuously. VERBAL INSTRUCTIONS Verbal instructions are often used in coaching, training, and rehabilitation. Verbal instructions can have an effect on someone's focus of attention and on the quality of their performance. One of the most important practices in learning is affective instructions because they can increase a performer's learning. Focus of attention includes external focus, internal focus, and neutral focus (Porter, 2011). According to the constrained action hypothesis, using external focus allows the body to control movements unconsciously (Zargami, et all, 2012, p.48). In contrast with internal focus of attention, it constrains the motor learning system. Due to this fact, movements become unstable and learning decreases. According to Zarhhami, Saemi, and Fathi, "when a learner focuses on the outcome of her/his movement then it is an external focus of attention" (2012, p.47). But on the other hand, when a learner focuses on her/his body parts it is an internal focus of attention (Wulf, Hob, & Prinz, 1998). Neutral focus of attention is when a performer does not focus internally or externally on purpose and just chooses his own. Some studies show that if participants choose their focus of attention, usually it is internal focus of attention because that is what they are used to. Many professional athletes use neutral focus of attention because that is what instructions they get from their coaches and practitioners. The examples of the internal and external focus of attention can be used in the discus throw: turn your right foot (internal focus of attention), turn your right shoe (external focus of attention). Another example of internal focus of attention is long sweep with your right leg from the back, and external example would be to use a cone and sweep around this cone. Many studies show that using external focus of attention helps to increase athletic performance such as vertical jumps (Wulf, Zachry, Granados, & Dufek, 2007), the standing long jump (Porter, Ostrowski, Nolan & Wu, 2010), and strength and conditioning training (Makaruk & Porter, 2014) represent a few studies implicating the value of external focus of attention. Details of the studies can be found in Table 1 below. There are several studies that were done involving throwing events, such as javelin throw, shot put, and discus throw. In the discus throw study, participants in an external group had to throw discus as far as they could, focusing on the landing location of the discus. In the internal group, participants had to throw discus as far as they could, focusing on the hand and wrist that is throwing discus. This study did not involve elite athletes or discus throwers. In this study, participants had limited knowledge about discus throw. The results showed significant difference between two groups. The average distance for EFOA (external focus of attention) was 20.49 meters and for IFOA (internal focus of attention) was 19.37. Discus throw, just as shot put or javelin throw, required force production and intramuscular coordination (Zarghami et all, 2012, p. 49). Force production plays a significant role in discus throw. Previous studies by Marchant et all (2011) investigated muscular activity during bicep curl. Participants had to focus on the bar when doing a curl and force production was measured and EMG (electromyography) to see muscle activation. The results show that participants were able to obtain greater force production using external focus of attention. These findings are beneficial for weightlifting and any exercises that involve force production such as throwing discus, shot put, long jump, vertical jump, basketball, volleyball and many others. The study by Asadi (2015) involved student athletes from the physical education institution that performed a novice javelin throwing skill. In IFOA, participants had to throw javelin with all their might while focusing on their hand; in EFOA, focus was on the javelin's trajectory. The last group had to focus on the landing-place. The last group performed better than any groups in external focus of attention. Participants performed lower in internal groups "adopting an external attentional focus, whether proximal or distal enhance motor performance in throwing distance" (Asadi, 2015, p. 6). Another study by Makaruk (2013) focused on shot put in elite athletes. This study included throwers, jumpers, and sprinters. Participants performed under head and overhead throw using IFOA, EFOA, and NFOA. The results show that EFOA group had father throwing distance than two other groups in both tasks. EFOA also resulted in a better trajectory angle (Ducharme et all, 2014). Overhead throw and underhand throw showed the same results, even though participants faced forward in underhand throw and backwards in overhead throw. "Having visual contact with the shot put and the landing sector is not necessary to benefit from an external focus of attention...the benefits of external focus of attention depend on cognitive and neuromuscular systems rather on the visual system" (Makaruk et all, 2013, p. 59 ). Overview of these studies will be beneficial for coaches in throwing events, especially the discus throws. Previous successful studies in focus of attention support our hypothesis that external focus of attention results in significantly better learning than internal focus of attention. There some studies that included elite, top-level, or high skilled athletes. The study by Wulf (2008) examined external focus of attention in elite acrobats. In this study, 12 world-class athletes and part of the Cirque du Soleil had to balance on a disk and look straight. The balance disk was on top of the force plate. They performed four 15s trial under each condition. Control condition is "stand still", external condition "focus on minimizing movements of the disk", and internal condition (focus on minimizing movements of the disk) (Wulf, 2009 p. 321). The study is unique because it did not support our prediction. The results were significantly higher under the control condition rather than external or internal conditions. This study does not generalize that external focus of attention can be applied to the elite performers. The similar study was done by Wulf et all. (2004, 2007), but it did not involve elite athletes, as participants were healthy younger adults. Participants enhanced their performance under external focus of attention in that study. In the study with elite performers, they improved their results when they choose their own focus of attention (control). According to Wulf, "It has been known that expert performers typically do not focus on the details of their actions, if they do - as often happen under increased pressure to perform well - their performance tends to suffer" (Wulf, 2008, p.323). Direct attention disturbs the motor control system that experts have used before. (Wulf, 2008). This study shows that there are some limitations by using external focus of attention in elite performers, and the performers did not benefit from it.

Another study that involved elite track and field athletes and coaches explained instructions and feedback given during practice and competitions among elite track athletes (Porter, Wu & Partridge, 2010, p. 200). The athletes had to answer several questions regarding what instructions and feedback they receive. 11 athletes responded that receive only internally focused instructions from their coaches during practice. Two responded that receive both external and internal. No athletes responded that receive just externally focused instructions. In addition, athletes were asked what they focus on during competition. Nine athletes reported that using internal cues, 1 reported uses external cues, 2 athletes use go back and forth between external and internal cues, and one did not provide a response. This study shows that most athletes receive internal cues during practice and competition. According to Porter, "It is our contention that this attentional strategy was facilitated by verbal instructions and feedback provided by their respective coaches during practice" (Porter, 2010, p.206). Many coaches are not aware of the current studies that provide that external focus of attention enhance performance.

Another study by Porter and Sims (2013) involved elite athletes in sprinting performance. It included highly trained collegiate football players. The researchers recorded their time at 10 and 20 yards, which is 9.14 and 18.28 meters. Participants had to complete three trials using each condition (external, internal and control). The results show no difference between the conditions in the first 10 yards (9.14m). In addition, there was no difference between times in the second 20 yards (18.28). However, there was a significantly difference in the second 10 yards (9.14m) in the control group. The difference was greater than in the internal or external groups. The internal and external had no differences between each other. It was predicted that using external focus of attention would enhance sprinting performance, but this study does not support that and does not support constrain action hypothesis. This study supports the result of Beilock, Castaneda and Gray that when studies involve high skilled experts "you do not want to direct their attention to the movement they are performing" (Porter & Sims, 2013, p. 47). There is an absence of the literature on biomechanical outcomes of discus throwing and focus of attention. There were some studies in biomechanics. We could combine studies in biomechanics and focus of attention to show that use of external focus of attention could enhance discus performance.

BIOMECHANICAL OUTCOMES According to Dapena et all (1997), there are many biomechanical factors in the discus throw, but we focus on two important ones, which are angular momentum about the vertical axis and vertical speed. The thrower first produced angular momentum in the double support at the beginning of the throw (swing back). Then, the thrower transfers as much of that angular momentum as possible from the body to the discus. This happens during the late part of the single-support on the right foot, but especially during the final double-support delivery phase. The important part is to maximize the angular momentum that the discus has at release. The second important factor is vertical speed of the discus at the end of the delivery phase (final position). This happens in two parts through 1. angular momentum about a horizontal axis aligned with the final direction of the throw and 2. an upward linear velocity of the whole body. It is important to have a big vertical velocity of the discus at release. But there is always a limit, it cannot be too much of vertical velocity. SOME OTHER IMPORTANT BIOMECHANICAL FACTORS IN DISCUS THROW Horizontal force that we receive from the ground is beneficial in several ways. First, it creates horizontal linear momentum for the thrower and discus system in the direction of the throw. The horizontal speed is added to the horizontal speed of the discus, which is created through angular momentum. Second, in the single-support phase at the back of the circle, this horizontal force is off-center relative to the c.m. of the thrower plus discus system, and therefore it contributes to the generation of angular momentum about the vertical axis. Third, when the left leg is planted in the front of the circle for the final double-support delivery phase that is when the horizontal velocity of the system can be used to help in the generation of upward linear velocity. Another factor is the angle of release. The angle of release depends on angular momentum and vertical speed. This angle should not be maximized. It needs to have an optimum angle, and this optimum angle depends on the wind conditions. One of the factors is the angle of tilt of the discus at release. This is an angle that also needs to have an optimum value, and that optimum value will depend on the wind conditions and on the angle of release. Fourth, center of mass height at discus release is a small factor, with a minimal contribution to the length of the throw. Every extra centimeter of vertical height at release adds Previous studies show that performance under external focus of attention resulted in significantly better results than internal focus of attention. Using internal focus depressed motor performance. It was supported in the previous study that putting a shot is strongly related to force production. When participants focus externally, they generate more force in comparison to when they focus internally. Wulf and Dusk (2009) found the results that in vertical jump, participants who focused externally produced a "greater center-of-mass displacement and jump impulse" (Makaruk et al., 2013, p.58). CONCLUSION The purpose of this article is to make coaches aware of the current research in motor learning and to introduce constraint action hypothesis, according to its performance benefits from adopting external rather than internal focus of attention. Direction-conscious attention disturbs the automatic process of motor behavior and results in lower motor performance. Coaches give instructions and provide feedback to their athletes. The instructions provided by coaches during practice influence the focus of attention during competition. Porter et all (2013) found that some coaches at the USA track and field championship in Eugene, Oregon provided feedback that was related to the movement of the body. 84.6% coaches instructed their athletes to focus internally and 69% indicated that they use internal cues while they compete. This study included 400m hurdles, 800 m, 1600m, 5000m, 100m sprint, 200 m sprint, javelin, triple jump, and decathlon athletes. Many coaches use different cues that work for their athletes. This is just an example; it does not mean that all coaches have to implement it. This just shows that for almost every internal cue, there is an external cue that can benefit the athlete's performance. This table shows that coaches should try to use external focus of attention so an athlete is not focusing on a particular part of the body because it constrains our motor learning system. Coaches should provide feedback and instructions that support external focus of attention. This alternative technique could result in enhancing performance. This might not go well with the "normal" training or what the coaches used to tell their athletes, but the scientific research is overwhelming on this topic. These cues could be practiced not just during practice, but competition as well. REFERENCE Asadi, A., Behrouz, A., Farsi, A., & Saemi, E. (2014). Effect of various attentional focus instructions on novice javelin throwing skill performance. Medicina Dello Sport, 67, 1-9. Dapena, J., LeBlanc, M.K., & Andrerst, W.J. (1997). Discus throw, #2 (Women). Report for Scientific Services Project (USATF). USA Track & Field, Indianapolis, 1-123. Ducharme, S.W., Wu, W.F.W., Lim, K., Porter, J.M., & Geraldo, F. (2015). Standing long jump performance with an external focus of attention is improved as a result of a more effective projective angle. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30, 276-281. Magil, R.A. (2011). Motor learning: Concepts and Applications (9th edition). New York: McGraw-Hill. Marchant, D.C., Greigg, M., Bullough, J., & Hitchen, D. (2011). Instructions to adopt an external focus enhance muscular endurance. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 3, 466-473. Makaruk, H., Porter, J, M., Czaplicki, A., Sadowski, J., & Sacewicz, T. (2012). The role of attentional focus in plyometric training. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 52, 319-327. Makaruk, H., Porter, J.M., & Makaruk, B. (2013). Acute effects of attentional focus on shot put performance in elite athletes. Kinesiology, 45, 55-62. Makaruk, H., & Porter, J.M. (2014). Focus of attention for strength and conditioning training. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 36, 16-22. Mkin, A.B., Winkelman, N., Porter, J., & Nimphium, S. (2016). Coaching instructions and cues for enhancing sprinting performance. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 38, 1-11. Porter, M.P., Anton, P.M., Winkoff, N.M., Ostrowski, J.B. (2013). Instructing skilled athletes to focus their attention externally at greater distances enhances jumping performance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 27, 2073-2078. Porter, J.M., Nolan, R.P., Ostrowski, E.J., & Wulf, G. (2010). Directing attention Porter, J.M. & Sims, B. (2013). Altering focus of attention influences elite athletes sprinting performance. International Journal of Coaching Science, 7, 41-51. Potter, J.P., Wu, W.F.W. & Partridge, J.A. (2013). Focus of attention and verbal instructions: Strategies for elite track and field coaches and athletes. Sport Science review, 3-4, 199-211. Raisbeck, L., Yamada, M., & Diekfuss, J. (2018). Focus of attention in trained distance runner. International Russell, R., Porter, J., & Campbell, O. (2014). An external skill focus is necessary to enhance performance. Journal of Motor Learning and Development, 2, 37-46. Saemi, E., Porter, J., Wulf, G., Ghotbi-Vanzaneh, A., & Bakhtiari, S. (2013). Adopting an external focus of attention facilitates motor learning in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Kinesiology, 45, 179-185. Schlesinger, M. Porter, J., & Russell, R. (2013). An external focus of attention Schucker, L., Hagemann, N., Strauss, B., & Volker, K. (2012). The effect of attentional focus on running economy. Journal of Sports Sciences, 27, 1241-1248. Winkelman, N.C., Clark, K.P., & Ryan, L.J. (2017). Experience level influences the effect of attentional focus on spring performance. Human Movement science, 52, 84-95. Wulf, G. (2008). Attentional focus effects in balance acrobats. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 79, 319-325. Wulf, G., & Dufek, J.S. (2009). Increased jump height with an external focus due to enhanced lower extremity joint kinetics. Journal of Motor Behavior, 41, 401-409. doi: Wulf, G., McNevin, N., & Shea, C.H. (2001). The automaticity of complex motor skill learning as a function of attentional focus. The quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 54 (4), 1143- 1154. Wulf, G., Hob, M., & Prinz, W. (1998). Instructions for motor learning: Differential effects of internal versus external focus of attention. Journal of Motor Behavior, 30, 169-179. Zarghami, M., Saemi, E., & Fathi, I. (2012). External focus of attention enhances discus throwing performance. Kinesiology, 44, 47-51. TATIANA ZHURAVLEVA IS A FORMER NCAA DIVISION II NATIONAL CHAMPION IN THE DISCUS WHILE COMPETING FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF INDIANAPOLIS. SHE WAS ALSO A MEMBER OF SEVERAL RUSSIAN FEDERATION NATIONAL TEAMS AND SERVED AS GRADUATE ASSISTANT COACH AT THE UNIVERSITY OF INDIANAPOLIS. |