| In Motion: Understanding the Psychological

Conditions of Run-Throughs |

| By: Stephan Munz

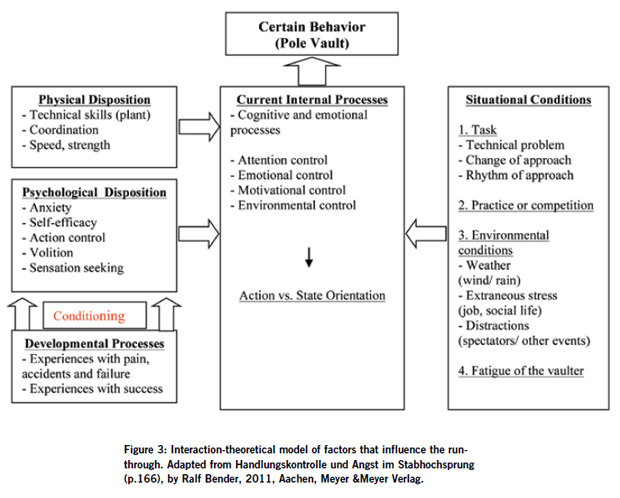

Originally Published in: Techniques Magazine Provided by: USTFCCCA The pole vault is one of the most challenging and technical events in track and field (Orden, 1984). High physical demands such as speed, strength, agility, body control and coordination are coupled with equally important psychological aspects; all of which play an important role in the performance development of athletes. Often, the psychological demands of the event are so high a stagnation in the development of the vaulter can result, mainly when psychological states such as fear, lack of concentration or insufficient action control predominate. The run-through, an abrupt cessation of motion during the take-off phase, results in the inability of the vaulter to finish the jump. This can be a challenging situation for a vaulter to overcome. Depending on the degree of the problem, the run-through can affect the vaulter's development for several weeks, months or, in severe cases, it can end the vaulter's career. If athletes and coaches understood the underlying psychological principles of the run-through, and if coaches had a toolbox of exercises and guidelines of how to intervene if running through occurs, the vaulter's performance development would be improved. It is the goal of this series of two articles to analyze and define the underlying psychological conditions of running through behavior and to provide practical principles and strategies coaches can use to decrease the frequency and severity of the run-through in their athletes. The first section focuses on the psychological theories that can explain running through behavior. It will also present an interactional model to serve as a framework for coaches to locate possible problems. The second section presents practical applications and exercises coaches and athletes can incorporate in their training environments in order to decrease the likelihood of running through. THE RUN-THROUGH Coaches who have experience with athletes who run-through typically face the following scenario: An athlete stands at his or her approach mark. The vaulter prepares for the jump, uses chalk for his hands and grabs the pole. The vaulter seems nervous and checks external conditions such as wind and the pole over and over again. Finally, the vaulter extends the pole into the air and begins the approach. The vaulter accelerates, starts dropping the pole and initiates the plant motion three steps before the take-off. On the penultimate step, the vaulter puts his hands over his head and prepares for an active take-off step. However, instead of taking-off into the air and bending the pole, the vaulter drops the pole into the box and runs onto the pit despite the fact that the take-off spot was right on the mark and the conditions appeared perfect for the vaulter to finish the jump. Similar scenarios often happen repeatedly. Running through can have different stages and patterns. Some vaulters suffer from running through for several practice sessions, others only run through during competitions and some may have running through problems for several months or years. The latter scenario often leads to stagnation or the end of a pole vaulter's career. Based on the analysis of the run-through frequency of German vaulters, Bender (2011) distinguishes between three different run-through types. There exists the vaulter that does not run-through at all, the vaulter who struggles with it occasionally or for inconsistent time periods, and the vaulter who has chronic running through problems over a long period of time. Bender also discovered that there are no significant differences among the age and gender of athletes when it comes to the frequency and severity of running through (Bender, 2011). A HOLISTIC MODEL OF THE RUN-THROUGH There are many psychological processes that occur between the intentional process and the actional process. Nolting and Paulus (1999) developed a behavioral model that helps to under-stand how intentional behaviors are influenced. The model explains how developmental conditions, personal dispositions, current internal processes and situational conditions affect and influence certain behaviors. Bender (2011) used this model to create a holistic picture of the factors influencing the run-through. Figure 3 shows an adaptation of Bender's model based on the principles of Nolting and Paulus. This model can serve coaches as a framework to identify possible variables that cause running through behavior. The model consists of three influencing components (developmental processes, physical and psychological dispositions, and situational conditions) that have an active impact on the internal cognitive and emotional processes of the athlete. The evaluation and results of these cognitive and emotional processes are the key components of how vaulters feel and evaluate their situation, resulting in a successful or unsuccessful execution of the take-off. The model can also serve as an orientation for other jumps coaches (long jump, triple jump, and high jump) if chocking occurs during the execution of the jump. DEVELOPMENTAL PROCESSES AND PSYCHOLOGICAL DISPOSITIONS The level of developmental processes, such as prior experiences, has a positive or negative effect on the personal disposition of the vaulter. These experiences can include accidents, pole break or periods of running through, but may also be moments of success, stability an practice or feelings of excitement. Such encounters work to shape the manifestation of personal dispositions such as anxiety, self-efficacy, and action control. The disposition for anxiety in particular can cause a conditioning process to occur. The following section analyzes this conditioning process. Additionally, the article will focus on the aforementioned components of anxiety, self-efficacy, action control and volition. In my opinion, these dispositions are the most complex and important ones concerning the causes of running through.

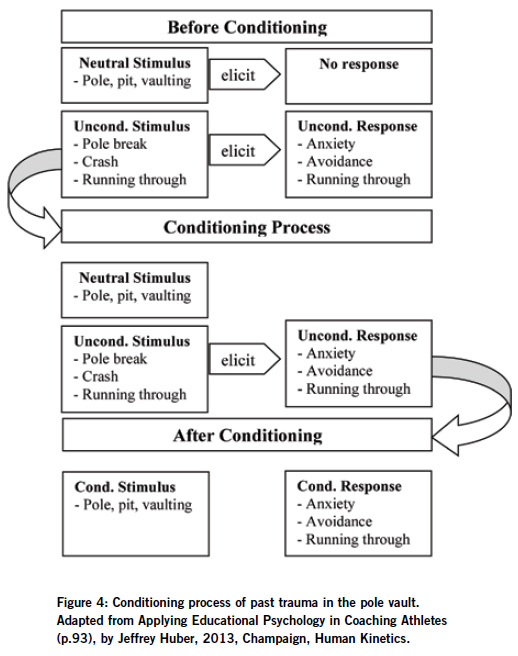

The consideration of psychological dispositions and traits in relation to the run-through assumes the fundamental units of personality are relatively stable. They influence the person to act in a certain way based on the level and degree of the disposition and are consistent across a variety of situations. For example, if an athlete's disposition of competitiveness is high, it is more likely that he or she will play hard and put forth high effort, regardless of the situation or score (Weinberg & Gould, 2011). However, these dispositions may change if an athlete experiences certain scenarios repeatedly. If vaulters experience multiple pole breaks or unsuccessful jumps, it will affect their degree of anxiety, self-efficacy, action control and volition in future situations. Anxiety. In his study about psycho-logical aspects of the pole vault, current German pole vault coach Joern Elberding (1998) asked thirteen German pole vaulters about the most critical factors that can lead to running through behavior. Interviews revealed that perceptions of danger and feelings of anxiety were the top components. This stands in agreement with the study of Bender (2011), who identified anxiety as the most important factor for running through behavior. Unlike state anxiety, a temporary, ever-changing emotional state of perceived feelings of apprehension and tension, trait anxiety is a behavioral disposition to perceive certain circumstances as threatening that objectively may not be dangerous, and to then respond with disproportionate state anxiety (Spielberger, 1966). This means that vaulters with high trait anxiety are more likely to experience apprehension and tension when they have to face challenging situations in the vault. Based on my personal experience as a former pole vaulter and current volunteer assistant coach, vaulters seem more likely to run-through if they face a last attempt scenario, difficult extraneous conditions, or if they go up a pole. How does a vaulter develop a high trait anxiety that can lead to running through? In some cases, the work of Ivan Pavlov, the Russian physiologist whose name has become a synonym for classical (respondent) conditioning, can provide an answer to this question. The following figure illustrates how pole breaks, failure, and crashes can condition the neutral stimulus of pole vaulting into a conditioned stimulus that results in anxiety and running through behavior.

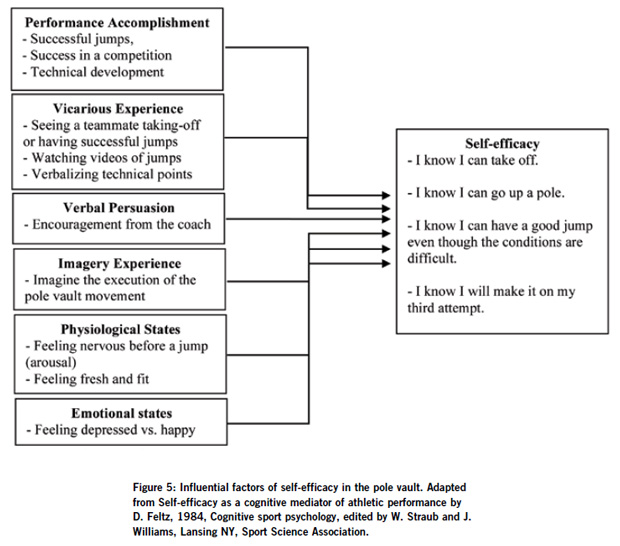

Neutral stimuli do not show any response before the conditioning process starts. However, unconditioned stimuli such as pole breaks, crashes or other negative experiences can elicit an unconditioned response. This process can lead to a conditioning process in which the neutral stimulus of the pole, pit, or the pole vault motion becomes a conditioned stimulus that elicits a conditioned response such as fear, dislike, or running through behavior. As a result, when this conditioning process comes into play, the vaulter will have a higher anxiety level when faced with the task of vaulting. The athlete can experience anxiety simply by thinking about the execution of the pole vault movement, or by looking at a pole or pole vault pit. Vaulters do not have to consciously think about their experiences with pole vaulting; they will simply react automatically when presented with pole vault stimuli. Consequently, it is crucial for coaches to ensure that athletes practice in a safe environment to avoid traumatic injuries and to sequentially master skills before progressing to more difficult tasks (Huber, 2013). The second paper of this two articles series will explain how coaches can decondition anxiety with a variety of exercises. It is important to note that the conditioning process in response to accidents or negative experiences can elicit running through behavior. However, the conditioning process is not the only reason why anxiety and avoidance behavior can occur. Other cognitive processes and theories can come into play as well, such as the conflict model of Dollard and Miller (1950), Epstein's theory of anxiety inhibition (1967), or Lazarus's theory of cognitive anxiety (1966). These theories, however, are beyond the scope of this paper. Self-efficacy. The influence of one's perception about personal skills and capabilities is equally important to the conditioning of anxiety when it comes to considering the running through behavior. If vaulters are confident about their skills, technical knowledge, speed and strength, it is more likely that they can overcome difficult scenarios and states of anxiety. A high level of confidence can lead to a more evolved perception and interpretation of bad experiences (Bandura, 1993, 1997). Psychologist Albert Bandura brought together the concepts of confidence and expectations to create a clear model of self-efficacy. According to Bandura (1997) self-efficacy is "the belief in one's capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments" (p. 3). This means that if someone has requisite skills and sufficient motivation, then the major determinant of the individual's performance is self-efficacy. Self-efficacy also affects choices, level of effort, and persistence of an athlete (Weinberg & Gould, 2011). For example, I believe that a vaulter with high self-efficacy will have fewer problems completing a jump in a meet when the extraneous conditions such as wind and other factors are not optimal. In addition, vaulters can overcome prior failure and bad experiences much easier, because they are aware of their skills and capabilities. The following model displays the factors that can influence a vaulter's self-efficacy. Volition and Action Control. It is interesting that some athletes are able to maintain their actions and achieve their goals, whereas others are incapable of transforming their motivation into action or cannot remain focused (Elbe, Szymanski, & Beckmann, 2005). For example, in the pole vault there may be two vaulters with the same level of motivation who are both willing to engage in the execution of the pole vault motion. However, one of the vaulters has the toughness and will to execute the movement under difficult conditions and the other vaulter runs-through. Kuhl (1987) makes the point that motivation leads to the decision to act. However, if an individual is already engaged, volitional action processes determine whether the intention will be executed or not. Volition is a construct from motivational psychology that describes self-regulatory processes that can protect the execution of an intention from extraneous variables. It is commonly referred as "the will" of a person to engage in a behavior. It deals with the processes that allow for the execution of an action despite internal and external resistance and the maintenance of the action until a specific goal is reached (Kuhl, 1983). The vaulter with high volition is less distracted and remains confident and positive during the execution of the movement even during harsh circumstances. Numerous studies have found that athletes with higher volitional skills are more likely to have better athletic achievements (Beckmann, 1999; Beckmann & Kazen, 1994).

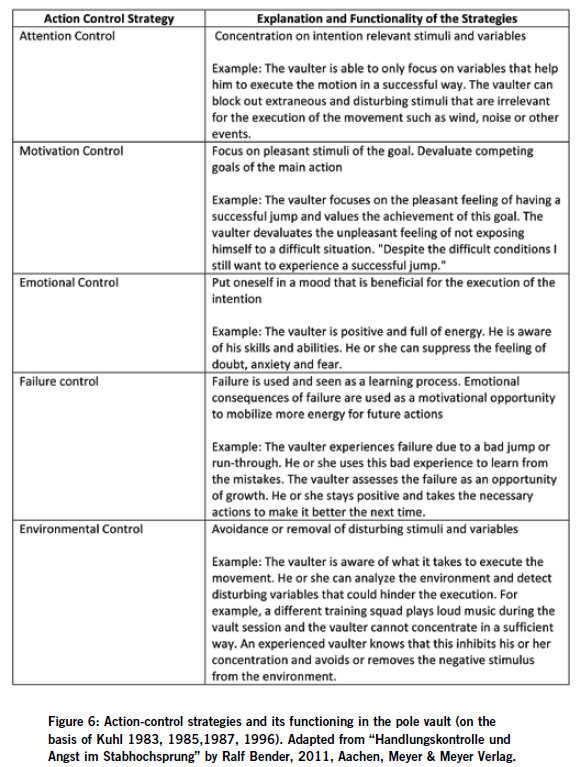

The underlying system of volition consists of several processes that are responsible for protecting and coordinating the intention of a specific action. These strategies can be seen as action control strategies and include attention control, motivation control, emotion control, failure control and limitation of information processing. Figure 6 illustrates the action control strategies and explains its functioning in the pole vault. At this point, it is important to note that there is a smooth transition between the psychological disposition or trait of an athlete and the current internal and emotional processes (See Figure 3). The processes of the action control are the current emotional and cognitive processes that take place in a vaulter's mind before or during the execution of a jump. The quality and evaluation of these processes determine whether the execution of the movement can be protected or not. In other words, the evaluation of the action control is a factor in whether or not the athlete runs through. There can be two outcomes based on the evaluation and result of the internal processes of the action control strategies. Based on Kuhl's (1983, 1985, 1987, 1996) interpretation of action-control strategies, one could argue that a vaulter is either in a state or action orientation. If the vaulter is in a state condition, he or she is likely to run-through. The vaulter loses control of the internal processes and evaluations and begins to fixate on the conditions of the current situation and consequences or situations of the past. This results in the vaulter expending energy and cognitive load on different scenarios and hypothetical situations. In this case, the vaulter will begin to shut down. For example, in the condition of state orientation, the vaulter would only think about the consequences of a bad jump or a run-through. The coordination of the action control strategies fall apart and the vaulter would continue running through. On the other hand, a vaulter in the state of action orientation is confident and does not think about negative consequences. He or she can protect the intention and execute the action in an efficient way. In addition, the vaulter is capable of making adaptations during the vault due to the fact that he or she did not waste cognitive load on second thoughts or doubts. As a result, the vaulter can focus on the correct execution of the pole vault motion. As a final result, one can say that the developmental processes, personal disposition (traits), and current internal processes (states) are all interrelated when it comes to running through behavior. Depending on the individual and the situation, the importance of each disposition or process can play a different role. Running through behavior is such a complex structure that it is impossible to create a holistic picture that is always applicable. There are also several other theories about anxiety, self-efficacy, motivation, stress, or volition that could provide explanations of running-through behavior. Another theoretical approach could be the sensation-seeking concept that is mentioned in Figure 3 under psychological dispositions. The concept attempts to explain how people with a high sensation-seeking tendency are more likely to engage in risky behaviors (Zuckermann, 1994). It can be assumed that vaulters with a high sensation-seeking trait are more action oriented when it comes to the execution of the pole vault movement, which is a risky activity itself. PHYSICAL AND TECHNICAL DISPOSITION Physical dispositions play an equally important role in regards to the running through behavior. First and foremost, the technical skills are critical. If a vaulter does not have a good approach rhythm and if the approach is not automated and accurate, the vaulter will be inconsistent and the take-off spot unstable. This can lead to insecurity, and the vaulter can lose the rhythm and feeling for the approach and take-off movement. In addition, the plant motion must be automated and technically correct. If the plant is too late and the arms are not accurately above the head after the penultimate step, the vaulter cannot engage in a proper and controlled take off-motion. A good understanding of the mechanics of the pole vault is fundamental to understanding causes and effects of running through, due to the complexity of the pole vault movement. However, a detailed technical and biomechanical analysis of the approach, plant, and take-off motion is beyond the scope of the analysis in this piece. SITUATIONAL CONDITIONS It should be obvious that difficult situational conditions, such as environment, fatigue, and task play an important role in running through behavior. Based on personal experience I believe that if vaulters are already unstable, disoriented or anxious, unfavorable situational conditions are the final triggering component that can cause a run-through. The first influential variable can be the task that vaulters have to execute. For instance, pole vaulters may have technical problems, or the coach may give them too many cues to focus on. If vaulters have to actively think and reflect about too many changes they want to make during the jump an overload of the cognitive capacity can occur. This can cause a shutdown of the movement, especially if the technical problems are based on the rhythm of the approach, plant, or take-off motion. Secondly, I believe that there are large discrepancies between practice and competition scenarios in terms of running through. Both scenarios can influence the run-through in a positive or negative way. For example, it is possible that vaulters have run-through problems in practice due to a lack of motivation or engagement, but vaulters do not run through in a competition because of the increased adrenaline and pressure of the meet. They are more focused and more consistent and energetic in terms of the execution of the movement. It can also be the other way around. Due to anxiety, stress, or nervousness vaulters can have severe run through issues during a competition, but none during practice. A competitive situation affiliated with stress or other extraneous variables such as loud noises or simultaneous events can reduce the concentration and attention control of vaulters. They are unable to focus on the execution of the movement and they cannot protect the intention of taking-off (see Figure 3: Current Internal Processes). Thirdly, environmental conditions can also play an important role in terms of situational conditions. A head or crosswind can make it extremely difficult for vaulters to execute the plant and take-off motion. In addition, it can be assumed that vaulters feel less confident and secure if they start the approach into a head wind. Vaulters can feel less powerful and develop second thoughts during the approach. If vaulters cannot control and suppress these thoughts with their action control strategies, it is likely that they become distracted during the approach and run through. However, further research needs to be conducted to support that thesis. An additional environmental condition can be unrelated stress in the vaulter's personal life. Social problems or stress in school or work can have a negative impact on the energy level and commitment of the vaulter. The vaulter is more preoccupied and less motivated due to the emotional burden. It can be assumed that the vaulter has less energy, which results in a reduced concentration level. The vaulter has more difficulties in protecting the intention of executing the movement. Fatigue of the vaulter is another situational condition. The pole vault is a challenging and exhausting event. Specifically at the end of a practice session or competition, vaulters experience the most tiredness and fatigue. Often times, a vaulter is on the largest pole at the end of practice or competition. This requires maximum concentration, energy and volition. However, the vaulter is less alert at this time due to the immense physical and mental stress. As a result, it can be possible that the vaulter loses the energy and commitment to finish the jump, resulting in running through. After presenting several variables that can influence running through, the next article will present guidelines and principles that can be applied to reduce the likelihood of the run-through. The holistic picture that was presented above should serve as an overview for coaches and athletes to evaluate and identify their own situation if they deal with continuous running through. The model can serve as an orientation and framework so that coaches and athletes may draw the right conclusions and intervene with the appropriate strategies.

REFERENCES Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational Psychologist, 28,117-148. Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman. Beckmann, J., & Kaze'n, M (1994). Action and state orientation and the performance of top athletes. In J. Kuhl, & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Volition and personality: Action and state orientation (pp. 439-451). Seattle: Hogrefe, 439-451. Beckmann, J. (1999). Volition und Sportliches Handeln [Volition and athletic performance]. In D. Alfermann, & O. Stoll (Eds.), Motivation und Volition im Sport—Vom Planen zum Handeln (pp. 13-26). Köln: bps-Verlag, 13-26. Bender, R. (2011). Handlungskontrolle und Angst im Stabhochsprung . Aachen : Meyer & Meyer Verlag. Dollard, J. & Miller, N.E. (1950). Personality and psychotherapy analysis in terms of learning, thinking, and culture. New York, NY, US: McGraw-Hill. Elbe, A., Szymanski, B., & Beckmann, J. (2005). The development of volition in young elite athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 6,559-569. Elberding, J. (1998). Psychologische Herausforderungen in der Sportart Stabhochsprung. Unpubished Diploma Thesis. Deutsche Sporthochschule Köln. Epstein, S. (1967). Toward a unified theory of anxiety. In B.A. Mahler (Ed.), Progress in experimental personality research (pp. 2-65). New York: Academic Press. Feltz, D.L. (1984b). Self-efficacy as a cognitive mediator of athletic performance. In W.F. Straub & J.M. Williams (Eds.), Cognitive sport psychology (pp. 191-198). Lansing, NY Sport Science Associates. Gollwitzer, P. M. (1996). Das Rubikonmodell der Handlungsphasen. In J. Kuhl & H. Heckhausen (Hrsg.), Motivation, Volition und Handlung (Enzyklopaedie der Psychologie: Themenbereich C, Theorie und Forschung: Ser. 4, Motivation und Emotion, Bd. 4, p. 427-468). Bern, Goettingen, Seattle, Toronto: Hogfere. Heckhausen, H. (1989). Motivation und Handeln (2. Auflage). Berlin: Springer. Heckhausen, I., & Heckhausen, H. (2006). Motivation und Handeln (3. Auflage). Berlin: Springer. Huber, J. (2013). Applying Educational Psychology in Coaching Athletes. Champaign: Human Kinteics. Kuhl, J. (1983). Motivation, Konflikt und Handlungskontrolle [Motivation, conflict and action control] . Berlin: Springer. Kuhl, J. (1985). Volitional mediators of cognitive-behavior consistency: Self regulatory processes and action versus state orientation. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckmann, Action control: From cognition to behavior (p. 101128). Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, Tokio: Springer. Kuhl, J. (1987). Action control: The main-tenance of motivational states. In F. Halisch, & J. Kuhl (Eds.), Motivation, intention, and volition. Berlin: Springer. Kuhl, J. (1996). Wille und Freiheitserleben: Formen der Selbststeuerung. In J. Kuhl & H. Heckhausen, Enzyklopiidie der Psychologie: Motivation, Volition und Handlung. Gottingen: Hogrefe. Lazarus, R.S. (1966). Psychological Stress and the Coping Process. New York: McGraw-Hill. Nolting, H., & Paulus, P. (1999). Psychologie lernen . Weinheim : Beltz. Orden J. (1984, May 22). Pole Vault may be track's hardest event. The Daily Reporter. Spielberger, C.D. (1966). Theory and research on anxiety. In C.D. Spielberger (Ed.), Anxiety and Behavior (pp. 3-22). New York: Academy Press. Weinberg, R.S., & Gould, D. (2011). Foundations of Sport and Exercise Psychology. Champaign: Human Kinetics. Zuckerman, M. (1994). Behavioral expressions and biosocial bases of sensation seeking. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Stephan Munz is a PhD candidate in Educational Psychology at Virginia Tech. As a student, Stephan focuses his research on theories of motivation both in the classroom and how they affect peak performance environments in coaching and athletics. Stephan received his undergraduate degree in sports science and biomechanics from the University of Stuttgart (Germany) and his master's in Educational Psychology at Virginia Tech where he was also a member of the pole vault team. Stephan currently serves as a volunteer assistant coach in the pole vault. |