| Strength & Conditioning - Program Design Fundamentals |

| By: John M. Cissik

Originally Published in: Techniques Magazine Provided by: USTFCCCA With that in mind, this article is going to provide some fundamental thoughts to help guide the track and field coach in the design of strength and conditioning programs for their athletes. These fundamentals are: • Apply the principles of training • Prioritize • Keep it in perspective • Link strength and conditioning to track and field training • Periodize APPLY THE PRINCIPLES OF TRAINING The principles of training have to be applied to any training program for it to be a successful one. Briefly, these principles are: Specificity: Specificity states that the body adapts to exercise according to the manner in which it is exercised. This applies to the muscles, joints and movements that are trained. In addition, it applies to energy systems and even to velocities of movement. This means that training programs have to be intentionally designed to help the athlete accomplish his or her goals. Overload: The overload principle states that once the body adapts to exercise, we have to find ways to make the exercise more difficult in order to force the body to continue adapting. In other words, to become stronger, you have to lift heavier weights as your strength increases. If you continue to lift the same weights, your gains will plateau and then reverse. Progression: The principle of progression views an athlete's career as a series of steps, each of which builds on the one that came before it. This means building a fitness base at the beginning of the year, learning exercise techniques and mastering fundamental movements before advanced ones, etc. PRIORITIZE On the surface, strengthening and conditioning has become very complicated and confusing over the last decade. Ten to fifteen years ago the focus was on lifting weights, such as learning the techniques of the foundational movements like the clean, snatch, squat, and bench press. Nowadays, there is a myriad of tools, and the marketing that accompanies them makes one think that they are all essential to the training of the track and field athlete. To further complicate matters, track and field athletes don't just lift weights. In addition to training in the weight room and on their event, they also travel, compete, go to school, work and have personal life interfere with everything. All of this means there is a very limited amount of time that an athlete has for training. This also means the athlete has a limited ability to recover from that training.

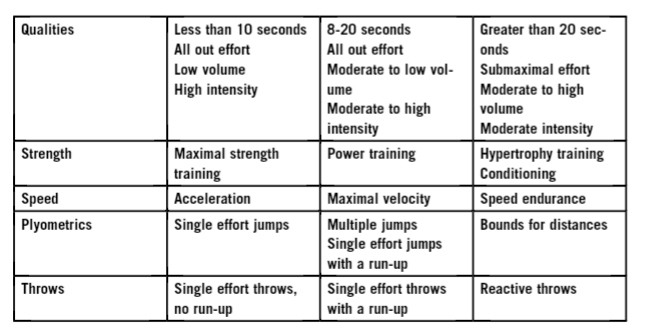

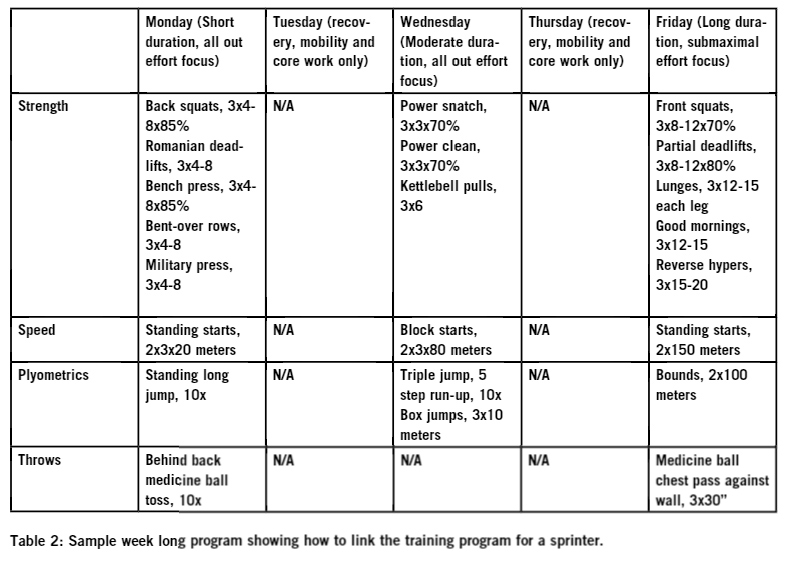

Table 1: Sample showing how different aspects of training can be linked according to physical qualities. In table 1, you can see that strength training with a maximal strength focus links up well with acceleration work, single effort jumps, and single effort throws. On the other hand, hypertrophy or conditioning-focused strength training links up well with speed endurance work, bounds for distances, and reactive throws (for example, a timed medicine ball chest pass). An example of this kind of linked training can be seen in table two. This is a program for a sprinter. If it were a different type of athlete (for example, a thrower) then the workouts would be different. If a coach isn't careful, they can use so many different tools in a strength and conditioning program to where they build an entirely ineffective program. At the end of the day, strength and conditioning exists to help the athlete perform better in his or her event, it's a means to an end and not the end. Track and field athletes need to be stronger, and they need to be able to express that strength quickly and they need to be able to apply all of that to their event. If a program focuses on those three things, then it's going to be a solid pro-gram, if it gets off course and loses focus then it's going to be a waste of the athlete's time. KEEP IT IN PERSPECTIVE Strength and conditioning is only one tool to help improve a track and field athlete's performance. Remember, our focus is on how well the athlete per-forms in his or her event and not on their weight room numbers. There are a lot of athletes who perform very well in the weight room, but who cannot perform in their events. Keeping things in perspective becomes imperative as athletes become higher level and start to approach their genetic limits. As athletes become stronger, it becomes more difficult to continue to increase their strength. As athletes approach their limits, it also increases the likelihood of an injury from training. This means that a coach needs to determine realistically how much strength his or her athletes need, at which point they should carefully weigh whether adding five more pounds to lift is going to be worth the risks to the athlete. LINK THE TRAINING A track and field athlete uses such a large variety of training tools and approaches that it is tough to balance everything out. They may sprint, condition, jump, throw, train for mobility, use core training, work on their flexibility, lift weights, etc. The list is very long. Within each training tool, there are different things that can be focused. For example, in sprinting we can focus on acceleration, maximum velocity, speed endurance, resisted sprinting, assisted sprinting, etc. This makes it very difficult to juggle a training program for a track and field athlete. Ideally, training should be put together so that all of the parts support and complement each other. If a coach is not careful, though, then it could be put together in such a manner that the parts interfere with each other. One approach to this is to consider what kinds of qualities we want to train and put the training together in a way that groups them together. The table below shows some examples of doing this. PERIODIZE Periodization is one of those topics that people overcomplicate. It's about a long-term approach to program design designed to make sure that the athletes are at their physical best at the right times. While this is being done the training is also balanced so that the athletes don't become overtrained or burned out. One of the challenges with periodization for the track and field athlete is that it involves every aspect of his or her training, not just lifting weights.

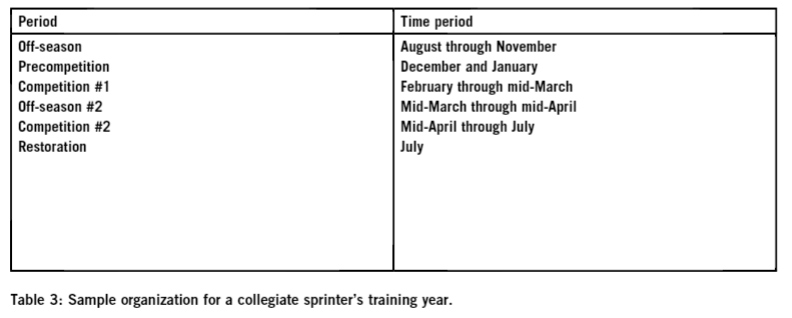

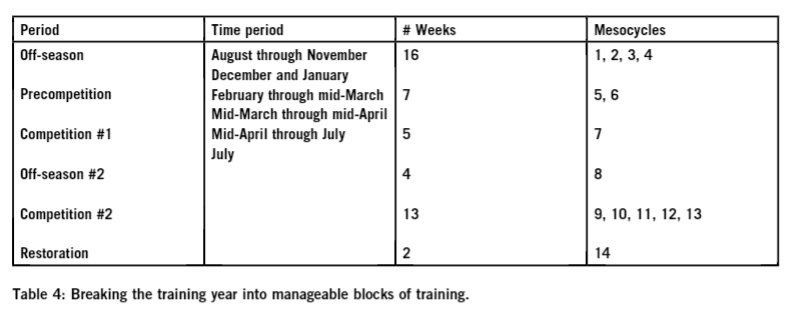

There are several steps to follow when designing a periodized program. These include: Organize the calendar Decide on the goals for each part of the calendar Determine the training means and methods for each part of the calendar Based on #2-#5, write the first four weeks Write the next four weeks as you are halfway through the first four Etc. ORGANIZE THE CALENDAR When organizing the calendar, start with when the athlete will be competing. The time around this is your competition period of training. Usually, four to six weeks before the competition phase is a pre-competition period. The rest of the year is your offseason. Table three shows an example of this for a collegiate sprinter. Note that there are two competition periods (Indoors and Outdoors). Once the calendar is organized, I like to organize each of these periods into two to four-week blocks of training. It helps to make things more manageable. Table four shows an example. The classic periodization literature calls these mesocycies, so for the sake of simplicity I'm keeping that terminology here.

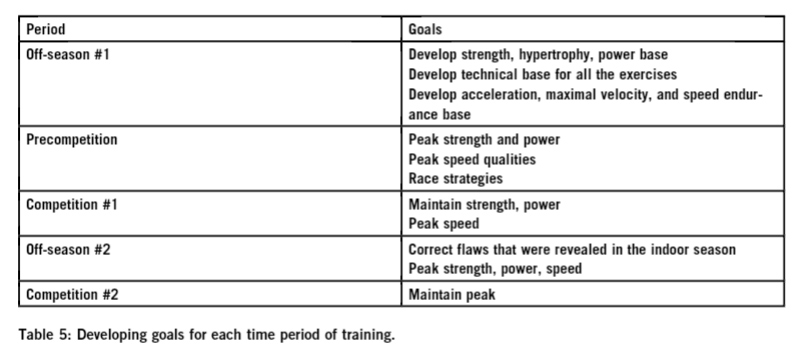

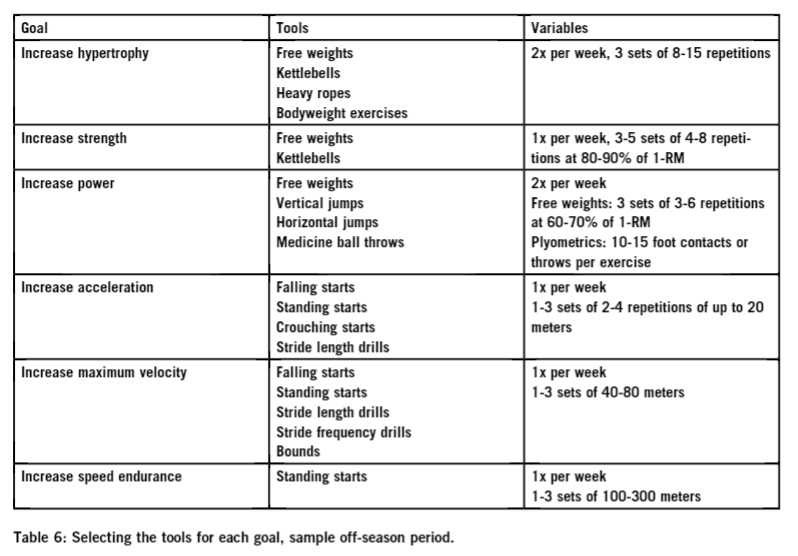

GOALS Once you have the big picture of the training program, it's time to decide on goals for each period. This is important, and a frequently overlooked, step. If this is done it will save a lot of time later on when it comes to writing the program. Table five shows an example of goals for each period. MEANS AND METHODS Once we know where our training is going, then it's appropriate to start thinking about how we're going to get there. This involves everything from thinking through the tools, to looking at programming variables in a very general sense. Table six shows an example of how to do this for the first offseason period. WRITING WORKOUTS Once all the above has been done, it's time to write the workouts while also keeping in mind every thing that has been covered in this article. Begin with the first four weeks, write this out in detail. Don't bother writing the rest of the program because real life is going to interfere with any plan that is longer than four weeks. If you have done all the steps that have been outlined, then you have enough information to be able to effectively write the other parts of this program. When you get half-way through the first four weeks, then sit down and write the next four weeks. Remember, test the athlete and assess how they are reacting to the program. Then make adjustments as necessary. Strength and conditioning can be a tool to help improve a track and field athlete's performance. It is also the kind of tool that is subject to misinformation and marketing which can make its effective use challenging for the track and field coach. When using strength and conditioning, it's important to apply the principles of exercise, prioritize training, keep it in perspective, link it to the rest of the training program so that all the components support each other, and to organize the program deliberately. John M. Cissik has been involved in strength and conditioning for more than twenty years, from commercial fitness, corporate fitness, universities, the Olympic level and administration. He has written ten books on strength and conditioning and is a past contributor to techniques. |