| High Hurdles: A Methodical Approach for Developing

High Hurdles |

| By:Karim Abdel Wahab

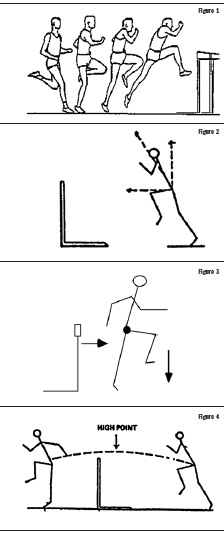

Originally Published in: Techniques Magazine Provided by: USTFCCCA This article includes the annual training plan for Colorado State University's high hurdlers, basic explanations of targeted performance criteria as well as the Ram's methodical approach in developing high hurdlers. The technical and physiological objectives of the training plan comply with the basic understanding of general biomechanics and sports physiology concepts held by the vast coaching community. ESTABLISHING A HIGH HURDLE DEVELOPMENT PHILOSIPHY Stride length and stride frequency are the parameters for faster sprinting. What about hurdling? In hurdling, stride frequency between hurdles is the limiting factor. A 15-second hurdler covers the race distance using the same number of strides as a 13-second hurdler; they both take 50 strides over the race distance (8 strides at the start + 3 strides between hurdles x 9 hurdle spacing + 10 hurdle clearance strides + 5 steps between the last hurdle and the finish line). Therefore, the ability to accelerate to the first hurdle, efficient hurdle clearance mechanics, stride frequency/efficiency between hurdles, re-accelerate after hurdle clearance, and the aggressive acceleration from the last hurdle to the finish line are the elements that need to be developed in any high hurdling training plan. What does it mean for hurdlers to be "aggressive"? Since the distance between the 10 hurdles is consistent, the "average" sprinting stride between hurdles will also have to be consistent, thus for hurdlers to run faster between hurdles they would have to turn over "shuffle" faster. "Shuffle" is a term that refers to sprinting faster between hurdles without any increase in stride length. If hurdlers develop a longer stride length than desired, they will "run out of room" and end up hitting or crashing into the hurdles. A longer stride length than desired between hurdles is the direct result of loss of the aggressiveness. hurdlers: Developing inner hurdling average stride length shuffling capabilities is crucial as previously mentioned, but general speed, strength, and power development qualities cannot be neglected in training. This recommendation strongly applies to hurdlers that do not have a high level of natural speed. The hurdler's sprint stride length during flat sprinting is typically greater than the average inner hurdler stride length. This allows hurdlers to sprint between hurdles at a lesser percentage of their maximum stride length, which will carry over to a faster frequency and better maintenance of rhythm throughout the high hurdle race. Hurdle clearance stride length: Hurdle clearance stride length is the distance between the point of planting the take-off foot at hurdle take-off and the point of ground contact at landing after the hurdle. Minimum loss of horizontal velocity: High hurdlers can not afford to lose much horizontal velocity throughout the race. Here are some general guidlines to minimize the loss of horizontal velocity in high hurdling: Getting in a tall body posture early enough before the first hurdle (Figure 1): Around the fifth stride the hurdler needs to transition to a tall upright body posture, to allow the center of mass to be at a maximally high launching level. Correspondingly, only a slight vertical impulse is needed to clear the hurdle, creating an optimal parabolic curve for the center of mass. Hence, the hurdler would be able to carry more velocity through the hurdle. "Power leg" and "Cut step" concepts at hurdle take-off (Figure 2) and re-accelerating after the hurdle (Figure 3): The trail leg or "power leg" is very special when it comes to power production. The steps taken by the trail leg are longer than the steps taken by the lead leg throughout the hurdle race. A hurdler uses their trail leg to perform two "cut step" actions, the first is during take-off and the second is during re-acceleration after the hurdle. The take-off step is typically shorter in length than the preceding stride, so the hurdler needs to actively "cut the take-off step" making sure the foot plants under the hips. This reduces the braking force and allows speed to be carried through the hurdle. Hurdlers need to have a lower heel recovery going into the take-off step to accomplish an active cut step at hurdle take-off. The second "cut step" is preformed after the hurdle by the trail leg at the get-away stride, the hurdler's foot actively lands under the hips to avoid braking force. This allows an efficient push-off action that will create an ideal re-acceleration between the hurdles. Taking off at an appropriate distance from the hurdles based on the hurdlers' height/anthropometric differences (Figure 4): Hurdlers need to take off at an appropriate distance from the hurdles to maintain an optimal horizontal parabolic curve. Thus, helping "displace the hips through the hurdles" with the minimal loss of horizontal velocity. If take-off is too close to the hurdle, then it will either result in crashing into the hurdle or jumping vertically to avoid the hurdle, in both cases there will be a great lose in horizontal velocity. Figure 4 is the "Model Take-Off Landing" table based on men and women hurdlers' height (Coach Curtis Frye).

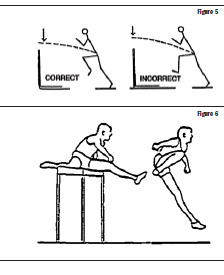

Minimizing the amortization at lead leg ground contact while landing after the hurdle (Figure 6): The lead leg should be grounded in an extended and vertical posture. It also must not yield to the landing pressure to which it's exposed after the hurdle clearance stride. This will prevent the drop of the center of mass at the landing after the hurdle, which can result in losing horizontal velocity. Eliminating the "slack" in the system while sprinting between the hurdles: Having a tall body posture while sprinting between the hurdles allows the hurdlers to carry as much horizontal velocity as possible. This tall body posture will put the hurdlers' muscular system under pre-tension. This will allow the hurdlers to take advantage of an effective and explosive stretch-shortening cycle in every stride between the hurdles.

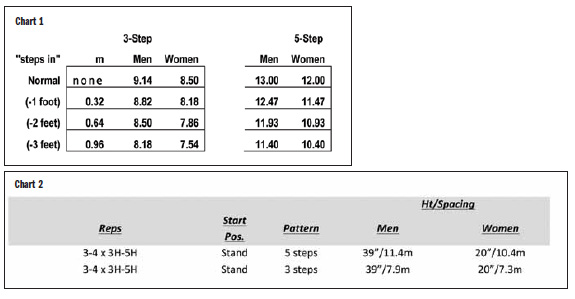

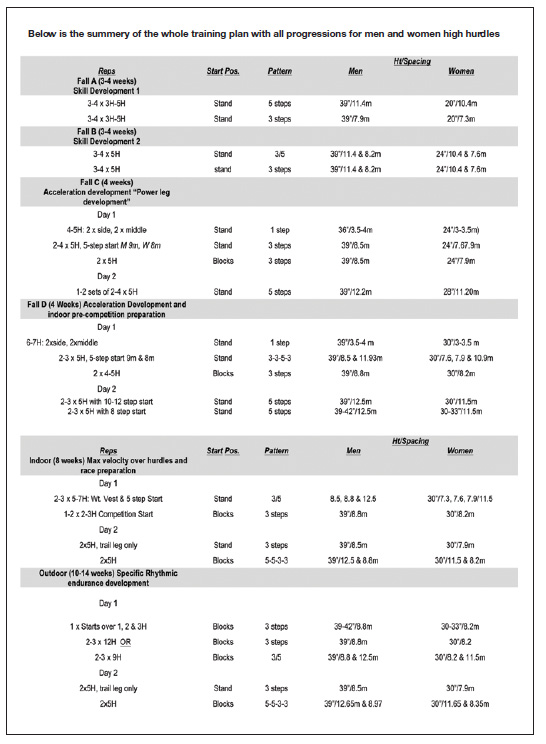

5-STEP PATTERN GUIDELINES 1. The hurdles inner spacing that is used during the training plan is typically shorter than regulation spacing, this develops turn over and proper "shuffling" capabilities for high hurdlers. 2. Over the six phases of the training plan the inner spacing progresses from shorter to longer and occasionally regulation spacing is implemented. 3. The 5-step stride patterns are used throughout the training plan for various objectives. The average stride length used in any 5 step stride pattern always mirrors the desired average stride length for the 3 step stride pattern implemented in any specific phase of training. 4. The main goal is to keep the hurdlers locked in using a consistent average stride length whether they use 3-step stride pattern or 5-step stride pattern in any given phase of training. Using 5-step stride patterns between any hurdling unit allows for velocity to carry over to a subsequent 3-step stride pattern unit. This will develop specific "shuffling" capabilities in every training phase. 5. The distance between hurdles for the 5-step pattern can be easily calculated. First subtract the hurdle stride length out of the desired distance between hurdles for 3-step pattern. Second, divide that number by 3, then multiplying it by 5 (these are the number of step utilized in inner hurdling stride patterns). Third, add the specific hurdle clearance stride length that corresponds to your athletes' height. 6. Take-off and landing distances should always be the same throughout the training plan to create consistency. This will make the development of the average stride's turnover become the prime focus of training. 7. The table below shows the distances in meters used in the 3-step inner spacing with corresponding 5-step patterns for a 5'10" male and 5'7" female hurdlers (Chart 1). THE TRAINING PLAN PHASE OBJECTIVE: 1. Proper take-off foot planting at hurdle take-off. 2. Developing proper take-off distance into the hurdle "more of a horizontal parabolic curve." 3. Leading with the knee with the lead leg at take-off. 4. Tight trail leg over and through the hurdle. 5. Trail leg landing after the hurdle with a positive shin angle at ground contact. 6. Tall body posture between the hurdles. 7. Teaching the skill of shuffling "turn-over" between the hurdles. (Chart 2). A. Max velocity speed work can be done after hurdling if needed: hurdle volume needs to be adjusted in that case. B. Hurdle-specifics strength endurance on a non-hurdling day, possibly done on the speed endurance day: reps of 20m A runs. C. Dedicate a day per week for acceleration development with no hurdles in this training phase. Max velocity work can also be done on the same day after the acceleration work. Notes: 1. Hurdling will be once a week in this phase. 2. Shorten the approach to the first hurdle 1 inch per-stride in this phase. 3. Use towels to mark take-off before hurdles. 4. Start in week one using 3 hurdles and progress gradually over the weeks to 5 hurdles. 5. 24"-27" hurdles are utilized for women starting this phase and throughout the training plan.

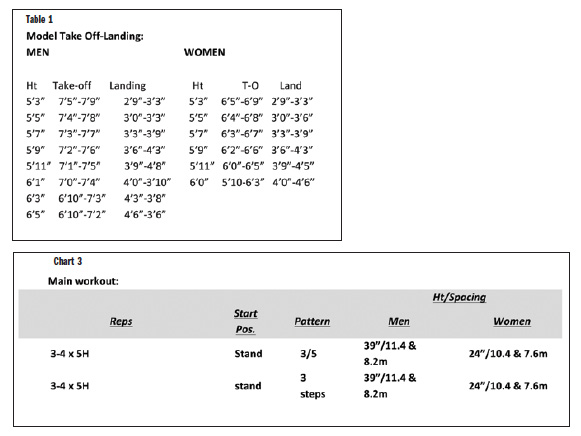

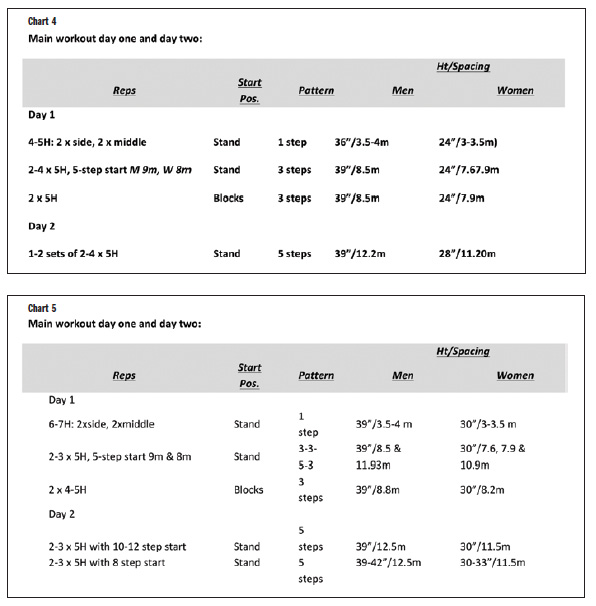

6. Using 5-step stride pattern allows: A. More time between the hurdles for the hurdler to respond to the coaching cues. B. Develop enough velocity between the hurdles, while utilizing tightly jammed running strides, to help make the skill of taking off far from the hurdles feels comfortable and attainable. 7. Using a standing start in this phase helps teaching the hurdlers the importance of a tall body posture at the first hurdle take-off. 8. Mark appropriate take-off and landing marks before and after each hurdle based on athletes' height (Table 1). FALL B PHASE OBJECTIVE: 1. Continue to teach and enforce the same qualities introduced in the last training phase. 2. Developing more coordination, turnover " shuffling" between the hurdles and enhance rhythmic qualities over the hurdles by adding more verity and mixing 3 and 5 step stride patterns in the same repetitions. (Chart 3). A. Max velocity speed work can be done after hurdling if needed: hurdle volume needs to be adjusted in that case. B. Hurdles specific Strength endurance on a non-hurdling day, possibly done on the speed endurance day: reps of 40m A runs. C. Dedicate a day per week for acceleration development with no hurdles in this training phase; Max velocity work can also be done on the same day after the acceleration work. Notes: 1. Hurdling is once a week in this phase. 2. Use towels to mark take-off before hurdle. 3. Shorten the approach to the first hurdle 1 inch per-stride in this phase. FALL C PHASE OBJECTIVE: 1. Power leg development "Trail leg cut step at take-off and trail leg re-acceleration after hurdles". 2. Developing a speed curve that is ideal over the first five hurdles "no crashing of speed curve after two to three hurdles, and accelerating through five hurdles at least." 3. Developing proper mechanics of block exit and approach to the first hurdle out of blocks. Notes regarding the 5-step start: In the next phase of training a 5-step start drill will be implemented. Hurdlers don't get much velocity built into the first _> hurdle when starting out of 5-step approach. Without much speed build in the first hurdle there won't be much room for error, take off foot should be planted properly "down and back" to create the cut step effect. Hurdlers need to be low over the hurdles to carry over as much velocity as possible "through the hurdle." There is no time for floating over the hurdles, "Lead leg and trail leg are racing to the ground" at landing after the hurdle. Trail leg will have to come through tight and land explosively with a positive shin angle at ground contact to start the aggressive re-acceleration and build more velocity between hurdles 1 and 2. There is no tolerance for over-striding between hurdles. To get to the next hurdle, faster hurdlers have to be efficient, aggressive and powerful. The coach is timing touch down units between a set of five hurdles and the timing units should be decreasing as the hurdlers are re-accelerating and efficiently creating more velocity. If they are not efficient and aggressive the speed curve will be slower over the five hurdles. Doing a few reps of the 5-step start drill followed by doing a few reps of the 8-step start out of blocks will create contrast training effect and will help carry over the efficiency and aggressiveness developed from the 5-step start to actual hurdling. (Chart 4). A. Hurdle volume can be reduced if flat acceleration or max velocity work needs to be done on the hurdling days. Notes: 1. Hurdling is twice a week in this phase. 2. Hurdles specific Strength endurance on a non-hurdling day, possibly done on the speed endurance day: reps of 60m A runs. 3. Frequency and volume of hurdle w-up drills are reduced. 4. Starting this training phase and until the end of the training plan start utilizing regulation distance for the start.

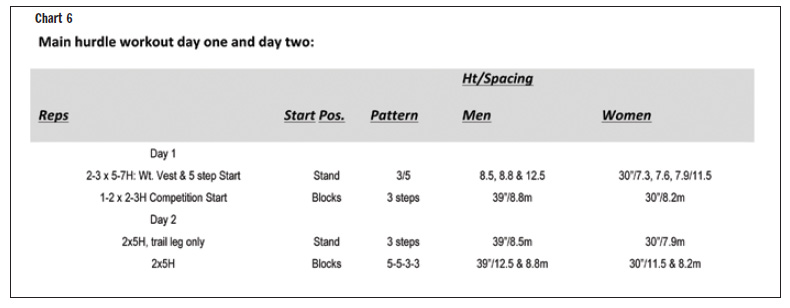

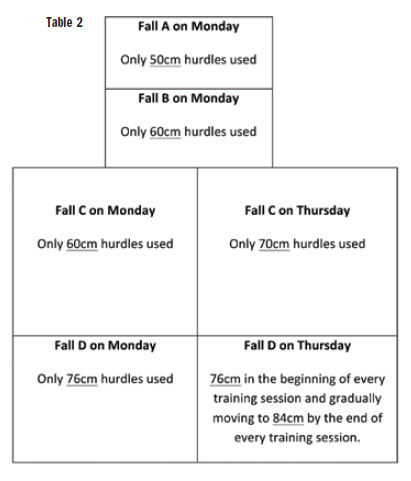

FALL D PHASE OBJECTIVE: 1. Continue to enforce and develop the "Power Leg" qualities as in the last training phase. 2. Improving the speed curve over five to six hurdles by continuing to enforce the qualities of re-acceleration, aggressiveness and efficiency as in the last training phase. 3. Developing proper mechanics of block exit and approach to the first hurdle out of blocks. 4. Introducing regulation height hurdling in parts of the workouts. 5. Introducing assisted regulation hurdling "Height and spacing": to help transition to full regulation hurdling in the upcoming competitive season "Indoor Track Season." (Chart 5). A. Hurdle volume can be reduced if flat acceleration or max velocity work needs to be done on the hurdling days. Notes: 1. Hurdling is twice a week in this phase. 2. Hurdles specific Strength endurance on a non-hurdling day, possibly done on the speed endurance day: reps of 80m A runs. 3. Frequency and volume of hurdle w-up drills are reduced. OVERVIEW ON WOMEN HURDLE HEIGHT PROGRESSION OVER THE FOUR TRAINING PHASES OF THE FALL • Women high hurdlers have a great advantage of minimally deviating from sprinting mechanic due to the shorter hurdle height when compared to the men's hurdle height. • The training plan progresses over the fall from 50 centimeters/20 inches gradually to 84 centimeters/33 inches to help develop confidence and establish a horizontal parabolic curve during hurdle clearance. • The aim is to teach women hurdlers to sprint through the hurdles and gradually increase the hurdle height while continue to emphasize sprinting through the hurdles. • The progression below shows the women's hurdle height increments utilized over the fall training period. (Table 2) INDOOR PHASE OBJECTIVE: 1. Maintain and enhance the power leg and re-acceleration qualities gained from the last phase. 2. Develop top speed over the hurdles. 3. Carry over all the qualities developed over regulation hurdling. 4. Model the sprint after the last hurdle to the finish line. 5. Prepare for races. (Chart 6). A. Hurdle volume can be reduced if flat acceleration or max velocity work needs to be done on the hurdling days. Notes: 1. Hurdling is twice a week in this phase plus a competition day over the weekend early season. 2. Late season and approaching main competition hurdling will be reduced to once a week plus a weekend competition. 3. Hurdling starts over up to two to three hurdles can be done on the pre-meet day according to athletes' type, needs and condition. 4. Hurdles specific Strength endurance maintenance: reps of 20m A runs. 5. Frequency and volume of hurdle w-up drills are reduced.

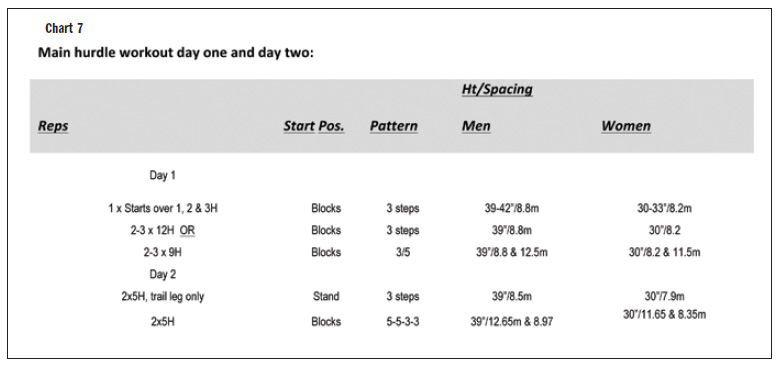

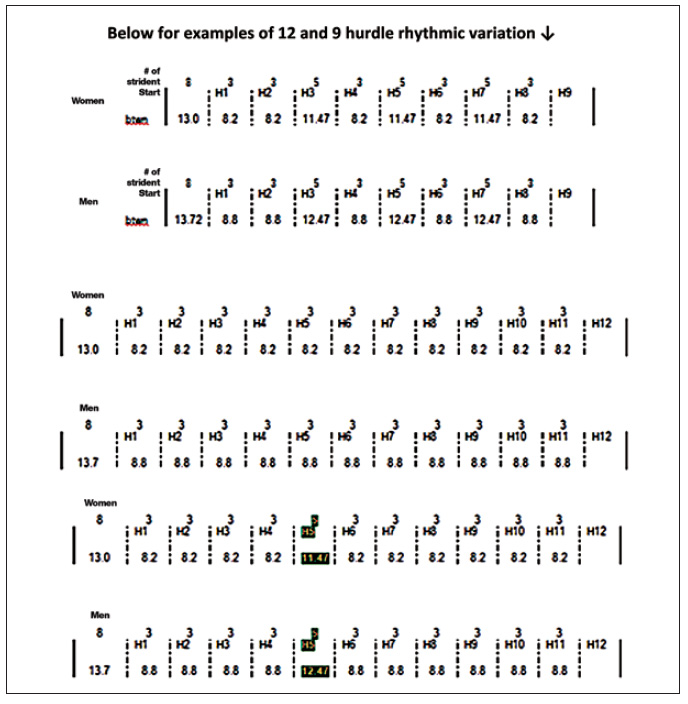

OUTDOORS PHASE OBJECTIVE: 1. Top speed development over hurdles. 2. Rehearsing starting mechanics and approach to hurdle 1. 3. Developing specific rhythmic endurance over hurdles. (Chart 7). A. Hurdle volume can be reduced if flat acceleration or max velocity work needs to be done on the hurdling days. Notes: 1. Hurdling is twice a week in this phase plus a competition day over the weekend early season. 2. Late season and approaching main competition hurdling will be reduced to once a week plus a weekend competition. 3. Hurdling starts over up to two to three hurdles can be done on the pre-meet day according to athletes' type, needs and condition. 4. Frequency and volume of hurdle w-up drills are reduced. 5. Hurdles strength endurance work using A runs is no longer utilized starting this training phase. TO PREDICT POTENTIAL COMPETITION TIMES IN PRACTICE For Women 100-meter hurdle: 12 hurdles at 76 centimeters x 8.2 meters between x 3-step all the way out of regulation start out of blocks (timing start with back foot leaving the blocks and stops at the touch down after hurdle number 12) take 0.5 second out to predict competition time. Example: If a woman's total time over the 12 hurdles drill is 14.30 seconds that means this woman is capable of running 13.80 seconds in competition. For Men 110-meter Hurdles: 12 hurdles at 99 centimeters x 8.8 meters between x 3 step all the way out of regulation start out of blocks (timing start with back foot leaving the blocks and stops at the touch down after hurdle number 12) Total time of the drill is potentially what they can do in competition. Example: If a man's total time over the 12 hurdles drill is 13.80 seconds, that means this man is capable of running 13.80 seconds in competition. REFERENCES Figures 1 and 6: Gunter Tidow (1991) Model technique analysis sheets for the hurdles Part VII: high hurdles. New Studies for Athletics 6;2; 51-66, 1991. Figures 2, 4 and 5: Brent McFarlane. THE WOMEN'S 100M HURDLES Figure 3: Gary Winckler (November 1994) Practical Biomechanics For the 100m Hurdles. USA Track & Field Heptathlon Summit. Model Take Off-Landing table: CURTIS FRYE. The High Hurdles: How to achieve |

The following philosophy and methodology were implemented in developing 2012, NCAA D-1 Second Team All-American student athlete, Trevor Brown, who lowered his PR in the 110-meter hurdles from 14.21 to 13.75 between his freshman and sophomore year, and moved up to be 8th in the NCAA D-1 110h finals in 2013 with a season best of 13.55(w) receiving a first team All-American Honors. Trevor's improvements in the 60 hurdles indoors were as follows: 8.30 in 2010 senior in High School over 42" hurdles, 7.91 freshmen in CSU, 7.86 sophomore and 7.77 Junior in 2013. Trevor currently holds CSU and the Mountain West Conference records in the 110- and 60-meter hurdles.

The following philosophy and methodology were implemented in developing 2012, NCAA D-1 Second Team All-American student athlete, Trevor Brown, who lowered his PR in the 110-meter hurdles from 14.21 to 13.75 between his freshman and sophomore year, and moved up to be 8th in the NCAA D-1 110h finals in 2013 with a season best of 13.55(w) receiving a first team All-American Honors. Trevor's improvements in the 60 hurdles indoors were as follows: 8.30 in 2010 senior in High School over 42" hurdles, 7.91 freshmen in CSU, 7.86 sophomore and 7.77 Junior in 2013. Trevor currently holds CSU and the Mountain West Conference records in the 110- and 60-meter hurdles. The hurdle clearance stride length will have to be consistent throughout the hurdle race for the average sprinting stride length between hurdles to be consistent. The consistency in the "average" stride length between hurdles, as well as, the length of the hurdle clearance stride are the keys for targeting turnover "shuffling" development in between the hurdles.

The hurdle clearance stride length will have to be consistent throughout the hurdle race for the average sprinting stride length between hurdles to be consistent. The consistency in the "average" stride length between hurdles, as well as, the length of the hurdle clearance stride are the keys for targeting turnover "shuffling" development in between the hurdles. Leading with the knee at the lead leg during hurdle take-off (Figure 5): Leading with the knee at take-off allows the avoidance of having a larger vertical parabolic curve of the center of mass at hurdle clearance. Leading with the knee will result in carrying a larger horizontal velocity through the hurdle.

Leading with the knee at the lead leg during hurdle take-off (Figure 5): Leading with the knee at take-off allows the avoidance of having a larger vertical parabolic curve of the center of mass at hurdle clearance. Leading with the knee will result in carrying a larger horizontal velocity through the hurdle.