|

A Special Relationship

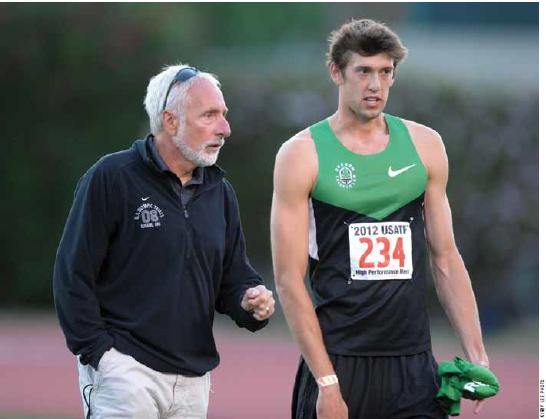

As athletic programs continue to grow in size and influence, so will the duty of care expected of all institutions and coaches. In contrast to traditional notions of a whistle-blowing and clipboard-carrying track coach, coaches may be required to do more than simply recite fundamental drills and proper training techniques. The steady rise in costly litigation and NCAA violations suggest coaches may be expected to act as risk managers to shield themselves and their employers against unreasonable risks (i.e., lawsuits stemming from wrongful conduct). In order to minimize their exposure to such liabilities, coaches should understand the scope of their legal duties. OBJECTIVE TORT LIABILITY IN GENERAL Traditionally, a party must prove four elements to establish a negligence claim: 1) Duty of care owed by the defendant; A duty of care is an obligation, recognized bylaw, that requires an individual's or group's conduct to be in accord with a particular standard (Wong, 2010). For instance, a person engaged in conduct as basic as crossing the street or as complex as that found in sports, has a corresponding legal duty to walk or play as an ordinarily prudent and reasonable person would; additionally, they should avoid creating unreasonable risks of injury to other persons. In sports, this duty requires athletes to exercise the "reasonable care" necessary to avoid creating risks potentially harmful to other players or spectators (Wong, 2010). Although the law expects us to take precautions against foresee-able risks of injury to other persons, one can imagine how flexible or even unfair this standard may seem at times. Moreover, other factors by law or status of the parties may limit or increase this reasonable care standard (e.g., employer-employee, coach-athlete, doctor-patient, priest-parishioner) (Wong, 2010). SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP: IS THERE A HEIGHTENED STANDARD FOR COACHES?  Similarly, in a Gettysburg College case, the courts discussed the specific nature of the duty owed to student athletes. The courts held the college breached the duty of care owed to its "recruited" student-athletes who were injured in competition (Wong, 2010). The court reasoned that an institution has a greater duty of care for recruited athletes than it has to students admitted under the traditional process. In contrast, a Massachusetts case found that Boston University owed no duty of care to protect the opposing team's basketball player from a punch thrown by a Boston University player when the school could not reasonably anticipate violence erupting (Wong, 2010). Simply put, the "special relationship" between an institution and its recruited student-athletes imposes a heightened duty of care on respective institutions. Most importantly, an institution's coaches and staff should provide for student-athletes' safety within the context of their sport. FAILURE TO PROVIDE ADEQUATE SUPERVISION

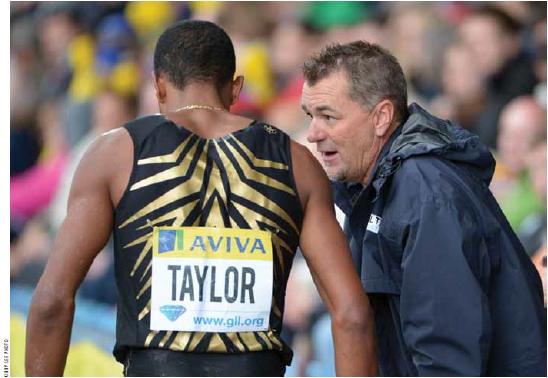

could be ready for the game. In the final decision, the Supreme Judicial Court of Maine suggested the coach had not exercised the reasonable care required of a similarly situated coach. When applied broadly, this duty may extend liability to coaches when he/she fails to control the actions of assistant coaches or staff or to properly examine the playing field or spectator areas (Wong, 2010). In the near future, coaches may be expected to take more affirmative steps in managing the scope of their duties—under a broader controlling principle. FAILURE TO PROVIDE PROPER INSTRUCTION AND TRAINING Coaches and assistant coaches are responsible for providing proper instruction and training to student-athletes (Wong, 2010). Generally, their education and training should meet standards specific to the sport, which may include undergraduate degrees, various certifications, and relevant experience (Wong, 2010). The coach additionally must competently instruct the student athletes on the activity, the safety rules and the proper methods of participating (Wong, 2010). In many lawsuits, injured players allege that the coach or teacher did not provide proper instruction and training (Wong, 2010). For instance, the first female high school football player in Carrol County, Md., sued the local school board after she was injured in her initial scrimmage. She claimed that high school authorities negligently failed to warn her and her family of the potential risk of injury and if they had been so warned, she would not have played nor would her mother have permitted her to do so. In siding with the school board, the court said the danger of football was "ordinary and obvious" and that school officials had no duty to warn the family of the danger. This case applies the well-established "assumption of the risk" doctrine that is a defense against liability when a person voluntarily participates in inherently high-risk activity—especially sports. The underlying logic is that such risks are considered widely apparent and any reasonable person participating in a sport should be aware of them. For instance, in track and field a hurdler assumes the risk of hitting hurdles and possibly injuring herself in practice or competition. Thus, to shift blame to someone else for an injury that normally occurs from participating in the activity would be unfair and unduly burdensome to coaches or other athletes. Although cases may turn on facts related to negligent supervision or inadequate instructions, initially the athlete assumes the primary risk of potential injury by voluntarily participating in the sport. In any event, it is wise practice for coaches to keep detailed records of their instructions, training logs and related materials to mitigate the damage of hidden liability issues. LIABILITY FOR THE ACTIONS OF FANS AND PLAYERS

tort of a fan or player, under the theory of vicarious liability (Wong, 2010). Although these cases are difficult to prove, some holdings suggest courts may be open to them in the future. For example, in a North Carolina case, a baseball umpire sued the manager and owner of a baseball team after a fan assaulted the umpire over a controversial call. The umpire claimed the manager failed to provide him adequate protection from an angry spectator and this negligent conduct was the proximate cause of his injuries. However, the court said physically violent disputes are not normal injuries that managers (i.e., coaches) could reasonably anticipate during a game; therefore the manager's conduct was not the proximate cause of the umpire's injury. This court's decision suggests that if the coach's conduct (intentional or unintentional) is more directly linked to the third party's injury, then courts may find the coach liable. For example, if a coach orders an athlete to purposely injure an opponent and the injury occurs, the coach may be liable under the vicarious liability theory (Wong, 2010). In a California ski team championship case, a plaintiff sued the school for harm caused by the allegedly reckless conduct of team member, who crashed into the plaintiff while she stood at the base of Mammoth Mountain ski run. The court held the school may be vicariously liable if the coach knew of the student's prior reckless tendencies but failed to take preventative measures. The court, by adding another layer to the reasonableness analysis, considered the student's prior conduct in assessing the coach's actions in the case. The facts showed the coach instructed the team to "take it slow and easy" before the competition and he had no reason to suspect the generally responsible student-athlete would act out of character. Consistent with the vicarious liability standard, the court's decision suggests the coach acted reasonably; and absent a prior showing of reckless conduct, there was no reason to impose a higher duty standard on the coach. Based on the above referenced cases, one thing remains clear: the facts of each case may be as indeterminate as determining the extent of a coach's corresponding duty. Although the issues addressed in the cases suggest a coach's duty may arise in seemingly remote instances, it is important to remember how he/she should mitigate risks where reasonably possible—a tough but necessary balancing act to maintain. As athletic departments continue to expand in size and influence, so will the expectations of coaches to observe and safeguard the interests of all legally concerned parties. These cases primarily address the duty element of the four- prong negligence claim. In the coming months, I will explore the other key elements of negligence claims associated with coaches in sports law. |

|

|