|

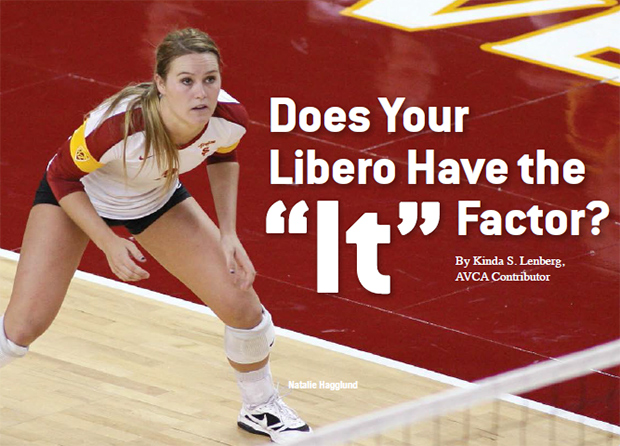

Does Your Libero Have the "it" Factor? By: Kinda S. Lenberg Originally Published in: Coaching Volleyball Magazine - AVCA

SOME VOLLEYBALL PLAYERS are born with "It." Others have "It" thrust upon them. Indeed, most coaches know "It" when they see "It." When it comes to the libero position in volleyball, what is the "It Factor" that makes a player — and as a result, a team — successful? The libero position, which the Federation Internationale de Volleyball (FIVB) instituted in 1998, has been successfully integrated into international matches, the men's and women's collegiate game, and boys'/girls' high school/club volleyball. Today, the libero is a highly regarded and integral part of a volleyball team at any level. As a result, coaches have spent the last decade and a half coming up with ways to measure and evaluate the person in that position. Interestingly enough, many of the top coaches in the country have determined the "It Factor" for the libero to be twofold. Indeed, the libero position has statistically significant measurables, from player height to wingspan to calculable passing ability. Simultaneously, however, the successful libero boasts some decidedly difficult-to-measure intangible assets such as the ability to anticipate, a never-say-die attitude and durability. Just how do these tangibles and intangibles fit together to form the successful libero? Physical Traits An excellent place to begin is with the physical traits of a libero. Not surprisingly, desirable physical traits vary from level to level, according to several of the top volleyball coaches in the country. Historically, the libero has been the smaller player, 5'1" to 5'8" or so. But, the times they are a-changin'. According to Cheryl Butler, co-director and master coach with Sports Performance Volleyball Club based in Aurora, Ill., "We try not to get the very, very small kids and make [the libero] a specific position. The 5'10" kid who is in seventh grade might be really tall, but if she stays 5'10" when she is a junior in high school, she is pretty small. As a result, we don't start specializing until the eighth or ninth grade year, so we don't use any libero before then! Then, we try to find somebody who is an outside or right side hitter who stopped growing at about 5'10." Jim Giacomazzi, who is the head women's volleyball coach at Wayland Baptist University (NAIA) in Plainview, Texas, as well as the founder/director of the Crown of Texas Volleyball club, agrees that for today's libero position, shorter is not always better. "I am all for the bigger [libero] being on the court," Giacomazzi explains. "There are six-footers who basically own that position. One or two steps and these players cover sideline to sideline with their physical stature." In the men's game, it would seem the maxim bigger is better fits the bill, especially on the U.S. Men's National Team, with tried and true tall liberos such as Rich Lambourne (6'3") and Erik Sullivan (6'5"); however, Kris Dorn, who is the head men's volleyball coach at Lindenwood University in St. Charles, Mo., disagrees. "I used to have a set of physical traits I looked for in the men's libero," Dorn explains, "then I have had two or three who have completely broken that mold. I used to err on the side of the six-foot, lanky, quick first-step player, and since then I have had liberos who were all the way down to 5'4" but super scrappy and covered a lot of ground because they were so close to the floor." Apparently, the "It Factor" does not come in a handy 5'5" package when it comes to the physical traits of the libero. What other measurables can help a coach predict future success for a player in this position? All coaches who contributed to this article agree that the ability to pass the ball, especially on serve receive, is crucial. Nearly all coaches in the game today utilize Dr. James Coleman's original statistical system that rates the effectiveness of a team's serve receive. Over the years, the scale has changed, but the idea remains the same: the pass is deemed a 0 if the passer is aced (no options are available to the setter); it is a 1 if the setter can set the ball but has no choices (or another player has to set); a 2 rating means the set is possible for two options; and a 3 translates into the passed ball reaching the target and all setting options are available. All coaches contributing to this article agree that a successful libero must consistently pass 2.5 or better. However, another "measurable" a couple of coaches discussed involve what they call the "perfect pass." For Butler, the perfect pass is "somewhere inside the 10-foot line in a small radius around where the setter stands." For Mick Haley, venerable head women's volleyball coach at the University of Southern California, as well as the 2000 U.S. Women's Olympic Volleyball Team head coach, "The most important thing is passing in the libero position. If you can get a player to execute a 3 pass seven out of 10 times, you have improved your ability to first ball kill. At the collegiate level, we look for anybody who can get a perfect pass 62 to 66 percent of the time." Russ Rose, revered head women's volleyball coach at Penn State, agrees, but with a slightly different twist. Giacomazzi admits, "I don't have a magic number. I am looking for a person who might have a reception error once every three matches." "You want the libero to take any free ball. Any little down ball possible so you can run your offense," Dorn adds. Dig It In addition to perfect passes on serve receive, the libero's ability to dig is the second most important trait, according to the aforementioned coaches. One of the most useful statistical categories in this case is the dig-to-kill statistic. Some coaches have the luxury of personnel to keep this statistic; others who have the personnel actually choose not to. For example, Rose states, "I don't have a dig-to-kill statistic. My stats at Penn State are, I think, atypical: If you have 10 balls and dig five, most coaches will say you dug five. I am interested in why you didn't dig the other five. I am waiting to find the 7/10 digger." According to Haley, "The most important trait of a libero is perfect passes; the bonus is the digging. But digs are somewhat elusive and you can't simply use number of digs because number of digs doesn't make any sense if you can't convert them to kills. As a result, the dig-to-kill percentage is the second most important thing we use to evaluate the libero. Internationally, you are looking at 22 percent dig-to-kill percentage...only two of 10 digs can be converted to a kill. Collegiately, you are looking at 32 to 38 percent. Natalie Hagglund (USC libero, 201114), for instance, was somewhere between 32 and 38 percent all four years that she was with USC, which means that we could convert three out of 10 to four out of 10 per kill on transition. That is pretty good." Interestingly enough, for Butler at the high school/club level, the order of importance is serve receive, serving and then digging. "When we rank our liberos," Butler ex-plains, "we look for passing and then we look for serving because really, if the libero doesn't score points for us, it is not an automatic point when they touch a ball. So they have to become point scorers somewhere within the game." Therefore, everyone agrees serve receive, digging and serving are the major components to track when evaluating a libero — but their order of importance varies from coach to coach.

|