| Discobolus

A New and Old Twist in Discus Technique By: D Scott Irving Originally Published in Techniques Magazine - Provided by: USTFCCCA

Old may not be quite the right word in the above title. Ancient may be the better word to describe twist in the context of this article. The most accurate Roman copy of the Greek original, Myron's Discobolus circa 450-460 BC, "...is today considered a rather inefficient way to throw the discus." While the reference in Wikipedia was clearly intended to underscore the limited rotation of the body in throwing the discus at the ancient games compared to modern discus technique, I beg to differ with the use of the word 'inefficient' and hope the words that follow will act as devil's advocate to get coaches thinking differently about the event technically, to give them a greater appreciation of the artistic essence of discus throwing, maybe even expand their technical creativity or, at the very least, open up discus throwing to more concerted biomechanical analysis. Why it took me nearly 40 years to figure out that the Greeks were pretty close technically regarding the discus throw is beyond me, especially considering that much of my undergraduate and graduate work was in art and art history. It also surprises me that others have not pushed discus technique in this direction, given the wealth of technological resources at our disposal, including biomechanics and computer graphics. Most of what I have to support my argument is based on empirical evidence. However, that evidence and experience over the past 40 years and more specifically the past three years, has thoroughly convinced me that not only were the Greeks on the right path technically, but that they helped put me on the right path. To understand what the Greeks were attempting to do technically with the discus throw, one must first understand that the ancient implement while similar in shape to the modern discus was typically larger and heavier and made of metal or stone in a variety of weights - 1.3kg-6.6kg. 6.6kg is over 14 pounds. Now that's heavy! It is difficult to even conceive a full throw, let alone a standing throw, using a 6.6kg discus, unless the thrower wishes to rip his shoulder out of its socket. Besides implement size, another difference between my throwers and the ancients was that the method of throwing the Greeks were using was little more than a standing throw. They were likely not establishing the same momentum that we hopefully should be getting beyond a standing throw. Although some research does suggest that the Greeks may have spun, my impression of Discobolus is that of a standing throw, mostly because of the extreme left foot turn in the statue. I believe it would be difficult to execute a full throw as we understand it today using the same mechanics. So suffice it to say that the basis of my technical argument lies within the context of the Greeks primarily executing standing throws.

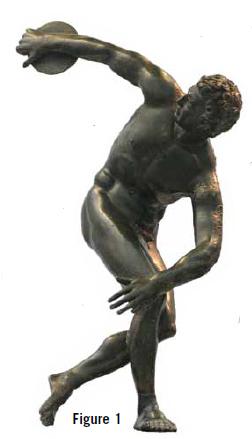

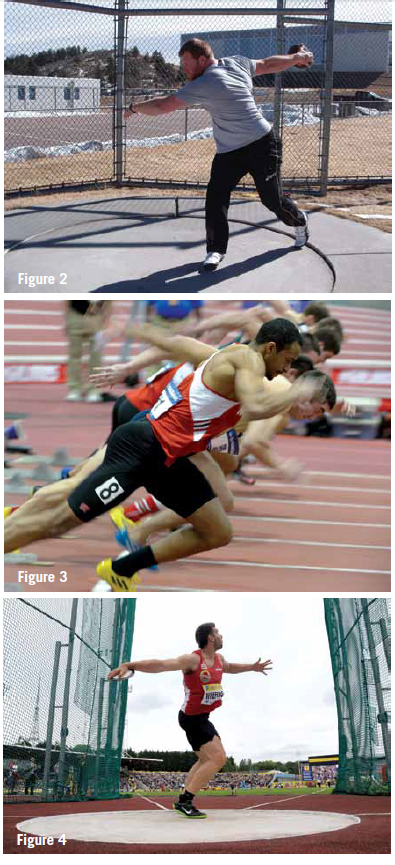

So, empirically at least, I have found that the Greeks threw similar distances out of their standing throws when compared to what the modern throwers of today (at least the ones I have coached) are capable of achieving with heavier implements. Throwers at other institutions may well throw farther with heavier implements, particularly from standing throws, than throwers I coached at the United States Air Force Academy, mostly owing to the mass of their throwers when compared to the lesser mass of the throwers at the Academy. In fact, most Academy throwers are much closer to the combined event body types of the ancient Games, keeping in mind that the discus throw was merely one of five events in the Greek pentathlon. The 2011 NCAA All-American and AFA discus record holder James Cole (183'9" 2kg college implement - 177' 1.6kg high school implement) stood 6'2" tall and a mere 195-2001bs at his peak, admittedly not your average size for a thrower in the NCAA Division I, and likely the reason I nicknamed him 'My Skinny.' He was probably closer in musculature, stature and symmetry to the ancient discus throwers of Greece, as expressed in Discobolus, when compared to his more massive counterparts in the NCAA. Yet, even though his competitors might have taken Cole for a decathlete he was able to compete against them quite well at the 2011 Drake Relays and in qualifying for the NCAA Championships. How was he able to do so? In my professional opinion, he was technically superior to his competition. Simply stated, he threw much more like the ancient Greeks and it merely required an additional twist. What is it that the Greeks did so differently and so well with their discus throwing technique? And throwing naked is not the answer. Although, it should be noted that the artistic nature of the throw was valued by the Greeks, even if the winner, as is the custom today, was determined by best marks. Greeks understood proportion, symmetry (symmetria) and rhythm (rhythmos). Pythagorus had established his theorem circa 540-530 BC, so one would also suspect that there was a scientific-mathematical-geometric basis to their concept of throwing, well before the time of Myron. Even the word technique is derived from the Greek word technikos which literally means artistic-skillful. Both the science and the art were indeed integral to the ancient Greeks. The Greek method of throwing might be deemed 'rather inefficient' only because it was a standing throw. It is my belief the Greeks understood the basics of throwing the discus quite well. The throwing arm (typically the right arm) on nearly every Dicobolus copy is at an approximate and appropriate ninety-degree angle in relation to the torso (Figure 1). Throwers strive for a very similar position today (Figure 2). In both ancient and modern throwers a technical effort is made to correctly keep the discus the greatest distance from the body. Geometrically speaking, the Greeks embraced this notion in Discobolus. The Discobolus torso is well balanced over the right leg and is slightly bent as it should be, as well as maintaining a nice parallel line with the lower left leg. Above all, the left arm is kept low, wrapped (back/closed) and in relative line with the throwing arm. Along with the turned head looking at the discus (not in agreement with looking at the discus - clarification later), these qualities combine to enhance the sense of being wound up and twisted back as far as possible. Additionally, Discobolus has established a stable and solid base. No doubt there are those coaches who will argue that the ancient Greek throwers, as expressed in Discobolus, bent over too much, created too much tension, had too narrow a base, etc. One comic misrepresentation of Discobolus found online even seems to skew Myron's classical intention. Do not get me wrong, I am not saying Dicobolus is technically perfect by any means, but I do strongly believe that we can learn from Myron's interpretation of ancient technique. It is important to be mindful that the discus in the day of the ancient Olympic Games was not only heavier than today's discus, but also typically bigger. As a result, it could not have been easy technically to elevate the discus on the wind up. Yet, it appears that the Greeks did not let the discus drop to their side which could well have been the more natural inclination for them given the weight and the size of the ancient implement. The Greeks were correct in not only attempting to elevate the implement to an acceptable angle; they also rightly bent or loaded their legs. They appeared to understand the basics of summation of forces - the legs needing to be activated first in order to apply efficient power to the implement. So, they were far from being 'inefficient' with their technique. In so many ways, they were right on technically. And, Cole was able to quickly assimilate this technically superior style into his full throws. Noted art historian Kenneth Clark observed in his book, The Nude, that, "....to the modern eye, it may seem Myron's desire for perfection has made him suppress too rigorously the sense of strain in the individual muscles." While I fully realize that the esteemed art historian was not a coach, I prefer to agree with Myron's interpretation in Discobolus. Up to this point, whether in a standing throw or other movement, it is my fervent belief that today's thrower should strive not to strain his muscles, but deliberately keep his emotions in check, be relaxed and composed. In fact, I do observe some unnecessary, albeit minimal, strain in Discobolus which is considered the most accurate Roman copy of the Greek original, the one in which Discobolus looks back at the discus. In order for a thrower to look back this far he would need to unnecessarily (again in my opinion) flex his sternocleidomastoid muscle in the left side of his neck. I totally agree with the full wind of the body. While Myron does an exceptional job sculpturally of conveying a good wrap of the torso, including the resultant tension of the abdominals, I feel that Discobolus' head should be relaxed and in line with the chest at this point, much like a sprinter. And, it is precisely this position where the torso is twisted and the head is in line with the chest that I feel every modern thrower should be striving to achieve; even as close as is reasonably possible in full throws when left foot touchdown has been achieved in the front of the ring. If I convey nothing else in this article, it would be this point and to some it may seem too extreme, but in my humble opinion it needs to be achieved in all aspects of throwing the discus, whether standing throw, mirror, Powell, or full throw. I have had a few throwers tell me that while it sounds like a great concept, it is one they cannot achieve. They argue that they either do not possess the requisite flexibility or the patience to make it work. To me, that is very much like a sprinter saying he cannot keep his head down when he drives out of the starting blocks. In order to be an exceptional, world-class sprinter, one must keep his head down out of the blocks for a few strides (Figure 3). This technical concept should be just as fundamental for the discus thrower as it is for the sprinter. Once a sprinter lifts his head up, he naturally stands up and misdirects the power he could have established in a more effective drive phase. A sprinter stands up if he looks up, because his eyes dictate where the cervical spine goes and the cervical spine dictates where the lumbar spine will go. The same is true for the discus thrower. Any coach who puts a discus in the hand of a novice thrower and asks him to execute a full throw for the very first time will normally find the young thrower looking first into the direction of the throw throughout the movement. This is only natural for the novice, but it is also horribly wrong. Sadly, even the most accomplished throwers of today throw this way, leading with their eyes and, as a result, their cervical spines and therefore their upper body throughout the throw (Figure 4).

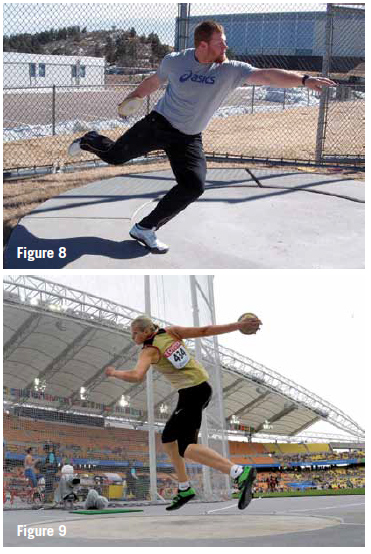

When the left foot touches down in the front of the ring following the drive across the ring in the full throw, it is absolutely imperative that the upper body still be in a `twisted' Discobolus position. It is my sincere contention that at the point of left foot touchdown nearly all competent, even today's world-class, discus throwers already have their shoulders squared to the back of the ring. Their focal point back may be excellent, but it is my belief that they have squandered a significant amount of range of motion in their torso and, therefore, pulling potential. They have also deliberately stalled their torsos when they focus back, waiting for the hips to lead the throw. This stall also seriously impedes the application of force by the legs while in the double support phase. You can call it staying closed longer, wrapping like the javelin. It really makes no difference to me what you choose to call it, but I am absolutely convinced that it is a key element in the world returning to greater consistency of 70+ meter throwers for men and for women. There may be a few skeptics out there who are set in their technical ways and feel this technical shift is way too extreme and too big a departure from conventional throwing. And that is fine. You will not offend me. I merely say, try it dogmatically and see if you do not experience a longer pull - a bigger sweep of the discus. In Cole, this is exactly what he and I sensed almost immediately (he physically and I visually) - a much greater sweep of the implement. He was not only My Skinny, he became my guinea pig, but with such a quick learning curve it did not take much to convince him or me that we were on to something big. From that point in his junior year at the Academy on we worked toward integrating that position into every drill, every facet and aspect of the throw. Wished he had one more year to compete. Sorry to say, no fifth year at an Academy. Still, it might be difficult for coaches to wrap their minds around throwing so wrapped, because it does so fly in the face of conventional wisdom - two focal points - front and back of the ring. East Germany's 1976 Olympic silver medalist Wolfgang Schmidt was very close to achieving this concept in his throws. His countryman, Martina Hellman, is the one world class thrower I have witnessed (European Championships - Stuttgart - 1986) who came the closest to achieving this head-torso relationship, near Discobolus position, on occasion. What I am asking coaches and throwers to consider is maximizing their full range of motion. And, by increasing this range, they are increasing their ability to more fully use their hips as well as more completely activating their core. Think of it simply as loading a spring by twisting the spring as tight as possible before you let it go. Then twist the spring about only half way around compared to the first trial and then let it go. Between those two which twist of the spring generates the highest resultant velocity? No question - the first. Obviously, we are talking in purely mechanical terms and the human anatomy is much more forgiving than a mechanical spring. With humans we have a much more complex system of summation of forces, i.e., foot to knee - knee to leg - leg to hip - hip to core -core to chest - chest to shoulder and finally the force is imparted to the implement. But it is my contention that nearly every thrower in the world today unwinds his anatomical spring (tension beginning with the core) too early throughout their movement across the ring and particularly with a significant loss of tension at left foot touchdown in the front of the ring. Basically, they lose the standing throw in their full throw. And, if they do, why even practice standing throws in the first place with the chest turned so far back when the thrower fails to do the same with their full throws? Some throwers tend to unwind horrendously, especially when they allow their left foot to open into the direction of the throw prior to left foot touchdown. One female 200'+ thrower I have coached did so, so egregiously in fact that her left foot would hover off the ground and turn in the air prior to touching down straight into the throw. What was the result? Not only did her upper body open up as the left foot was working to touch down, but she was also slowing down which made her technique all the more deficient. It not only took her longer to get into her double support phase, it also made her unable to apply force on the implement from a maximal length of pull. And she still threw 200'+. Maybe the wait for the left foot was only a split second, but I can only imagine how much farther she could have been throwing had her anatomical spring been fully loaded like Discobolus. To more completely understand his point, I would invite the readers to place themselves in a standing throw position - no discus required. Once in this position turn your left foot totally into the direction of the throw. Unless you are an anatomic freak, you should find that you cannot wind your chest back fully, like Discobolus, with the left foot pointed straight into the throwing direction. Most will also find that the position of the left foot restricts their ability to turn their torso back into the standing throw position. In fact, if a thrower touches down in this manner with the left foot turned totally into the throwing direction, it forces the thrower to open his torso into the throwing direction prematurely. This should be evidence enough to demonstrate that the anatomical spring has been prematurely unwound and, therefore, the length of pull seriously compromised. So, how does a thrower incorporate the standing position into the full throw? The same way James Cole did in practice and competition. He incorporated the standing throw into every drill and aspect of his practice and competition routine with repetition - repetition - repetition. One point of clarification needs to be made here in my meaning and in Discobolus' intent. When speaking of left foot touchdown in the front of the ring, please do not confuse this with left heel touchdown in the front of the ring. When a thrower takes their big wind up with their torso for a standing throw they, like Discobolus, must pivot their left foot and the bottom of their left foot inevitably points in the direction of the throw (again Figure 1 & 2). In his excellent six part YouTube video Wolfgang Schmidt rightly speaks of getting his left foot through the center of the ring and down quickly in the front of the ring. This is a key element of being able to wait on the upper body, a la Martina Hellman, and not so unlike Schmidt, who I believe would agree that on his better throws he was still looking to the back of the ring as he began the pivot on his right foot in the center of the ring following left foot touchdown. This is also the main reason I use the technical cue of pivot - focus back rather than focus - pivot. It may seem like semantics, but it is effective and it works. We drill this concept of focal points, as well as the additional twist relentlessly. So please understand that our throwers are attempting to touch down with the toes of their left foot. The left foot does very slightly rotate in the air prior to contact with the ring, but slightly sidewise - not totally rotated into the throwing direction. Upon contact the left foot pivots quickly to left heel touchdown. At the same time the torso moves in concert with the left foot the right foot begins a quick pivot in the center of the ring. These are all obviously very synchronized movements in concert with one another, but they are all elemental and fundamental to establishing not only double support, but also the momentum and timing necessary to maximize angular velocity at release. Recommend the following progressions and concentration. Standing throw (Figure 5 - prefer right arm up slightly higher than shown in figure - in line with left arm) - normal wind with head in line with the chest, striving to focus between zero degrees (back of the ring) and 270 degrees. Consider the position of the left foot at this set up point and try to recreate the same sensation and position throughout the throwing progressions. Done correctly, the path of the discus becomes a much bigger J shape and the thrower should begin to sense this sweep throughout the following throwing progressions. Mirror/step through throw - As the name implies, set up as though you have already moved across the ring with the right foot touched down in the center, the left foot still straight on as if pushing through the ring and the eyes focused out into the field (Figure 6). Many throwers will set this up by already turning their head to the side, wishing to look to the back of the ring pre-maturely with both feet turned sideways (Figure 7). Some throwers turn even farther than the figure shows. In my opinion this is a very big mistake, because the thrower is encouraging leading with the upper body into the throw and this negates nearly all tension of the anatomical spring. In order to maximize the spring, I would encourage the thrower to set the starting position in as strict a manner as possible. Let the throwing arm and discus relax, then begin the movement of shooting the left leg past the right, but at the same time allowing the upper body torso to remain relaxed. Initiate the movement with the legs and the right hip pressing up into the throwing direction. This will allow the discus to follow a natural path and plane in line with where it began, low and behind the hip - some may say much like walking a dog. The position the thrower is striving for is exactly that same position the thrower established in the standing throw. Above all, do not forget the bigger elliptical path, loop or J that the discus is now following. The thrower needs to practice this over and over in order to ultimately incorporate it into the full throw. Powell or Wilkins across the ring -depending on the thrower. Whether you are trying to work a more linear or rotational (Figure 8 next page) path across the ring, really matters little to me. What I am trying to convey in this article is that you need to incorporate the exact sensation as the mirror into this movement. However, it is important no matter which method you choose that the thrower's left foot is close to the right foot and passing it at right foot touchdown in the center of the ring. As in the mirror throw, when the left foot passes the right in the center of the ring, the focal point should be still somewhat for-ward with the head in line with the thrower's chest. At this moment, most throwers tense up in preparation to throw, preferring to lead with their head rather than their legs (Figure 9). Much like the mirror it is paramount that the same standing throw position be achieved prior to completing the throw. Fulls - same as above with the exception of the complete movement out of the back of the ring in a full throw. If the thrower still struggles to establish the standing throw position suggested here and still looks into the throw, I would advise the following drill - continuous cross steps in Powell or Wilkins movement. After a few cross steps, turn and hold the standing throw position, with the additional twist, gripping the implement or another object and not throwing. Indeed, it takes discipline to achieve this position, the same kind of discipline it takes to set the body correctly over the left leg out of the back of the ring. However, if a thrower can manage that discipline to properly execute this fundamental I am convinced that the return will be of immense proportions. And once a solid command of this position is achieved then the thrower can also throw out of this drill, either off a road into a field or off the javelin runway. (Be mindful that the thrower is therefore not throwing out of a ring, and coaches and other athletes need to be safely out of the way and out of range of any mis-guided throws.)

References Wikipedia - The Free Encyclopedia. http:IIen.wikipedia.orglwikilDiscobolus Remijsen, Sofie and Clarysse, Willy (2012 — KU Lueven) Ancient Olympics — Discus throwing. http:Ilancientolympics.arts.kuleuven.belenglT0004EIV.html Swaddling, Judith (1999 — 2nd Edition) The Ancient Olympic Games. University of Texas Press, p. 66. Miller, Stephen G. (2004) Ancient Greek Athletics. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, p. 61. Clark, Kenneth (2010) The Nude: A study in ideal form. New edition. London: The Folio Society, pp. 134-135. Special thanks to Russ Winger for assisting in the photo process.

D Scott Irving is the recently retired Men's and Women's Track & Field field event coach at the United States Air Force Academy. He can be reached for discussion or comments at dscottirving@gmail.com

|

For the purposes of testing throwers using over-weight implements, I would allow my athletes to use whatever starting position felt the most comfortable or natural. For the younger throwers that might well be a standing throw with the heavy plate, so they had no real advantage over the Greeks, except that our heavy plates are likely closer to the size of the modern men's and women's implements. For more accomplished throwers either a step through/mirror throw or a Powell/South African movement through the ring might be used. The most technically proficient throwers normally use a full throw for testing purposes. (A word to the wise coach, if you experiment with over-weighted implements in training and have your athletes throw multiple repetitions, I would strongly advise not throwing more than 5lbs plates for women and 7.51bs plates for men, especially in a semi-competitive setting and particularly with full throws - unless, of course, you really do wish to blow out a shoulder joint. You would also be wise to progressively build up on the number of throws you take with heavier implements. If you do throw heavier discs/plates you can risk injury, particularly in the region of the shoulder, deltoid and biceps tendon, and the chest, pectoralis major and minor. Please trust my experience here and be cautious.)Warm up properly beginning with standing throws, progressing up to mirrors/Powells - if you prefer South Africans and eventually full throws.

For the purposes of testing throwers using over-weight implements, I would allow my athletes to use whatever starting position felt the most comfortable or natural. For the younger throwers that might well be a standing throw with the heavy plate, so they had no real advantage over the Greeks, except that our heavy plates are likely closer to the size of the modern men's and women's implements. For more accomplished throwers either a step through/mirror throw or a Powell/South African movement through the ring might be used. The most technically proficient throwers normally use a full throw for testing purposes. (A word to the wise coach, if you experiment with over-weighted implements in training and have your athletes throw multiple repetitions, I would strongly advise not throwing more than 5lbs plates for women and 7.51bs plates for men, especially in a semi-competitive setting and particularly with full throws - unless, of course, you really do wish to blow out a shoulder joint. You would also be wise to progressively build up on the number of throws you take with heavier implements. If you do throw heavier discs/plates you can risk injury, particularly in the region of the shoulder, deltoid and biceps tendon, and the chest, pectoralis major and minor. Please trust my experience here and be cautious.)Warm up properly beginning with standing throws, progressing up to mirrors/Powells - if you prefer South Africans and eventually full throws. The Greeks realized this over two thousand years ago when they tried to maximize a full range of motion over which to apply force. Since theirs was primarily a standing throw they needed an extreme wind up, as well as a slightly exaggerated bend in the torso. Most throwers today do twist their torsos clockwise for right handed throwers similar to the Discobolus on standing throws, but they usually do not bother keeping the head in line with the chest. I encourage those who have a Mac Wilkins video/DVD, 'Gold Medal Discus Throwing,' to pause one of the standing throw demos at complete wind up. Where is his chest? Wilkins torques/winds his torso back beautifully like Discobolus, but unlike Discobolus he looks straight back and does not move his head in line with his chest. Most throwers today, like Wilkins, do at least try to look straight back when setting up the standing throw, and that may be easier and less awkward than turning their heads farther, but in my estimation it is not the most efficient approach to throwing the discus technically correct. It is also the reason that most young throwers often struggle in distance thrown when comparing their standing throws to full throws. The comment is often made in frustration that, "My standing throws go as far or farther than my full throws." It is my contention that even the best throwers in the world would do well if they could bring more of their standing throws into their full throws. And please know that I am not talking about loading up to throw when I mention bringing the standing throw position into the full throw. Nothing could be further from the truth. How can throwers bring the natural standing throw position into their full throws and in so doing maximize power in their full throws? It is actually pretty simple on paper to explain, much more difficult to put into practice. Please consider the following closely.

The Greeks realized this over two thousand years ago when they tried to maximize a full range of motion over which to apply force. Since theirs was primarily a standing throw they needed an extreme wind up, as well as a slightly exaggerated bend in the torso. Most throwers today do twist their torsos clockwise for right handed throwers similar to the Discobolus on standing throws, but they usually do not bother keeping the head in line with the chest. I encourage those who have a Mac Wilkins video/DVD, 'Gold Medal Discus Throwing,' to pause one of the standing throw demos at complete wind up. Where is his chest? Wilkins torques/winds his torso back beautifully like Discobolus, but unlike Discobolus he looks straight back and does not move his head in line with his chest. Most throwers today, like Wilkins, do at least try to look straight back when setting up the standing throw, and that may be easier and less awkward than turning their heads farther, but in my estimation it is not the most efficient approach to throwing the discus technically correct. It is also the reason that most young throwers often struggle in distance thrown when comparing their standing throws to full throws. The comment is often made in frustration that, "My standing throws go as far or farther than my full throws." It is my contention that even the best throwers in the world would do well if they could bring more of their standing throws into their full throws. And please know that I am not talking about loading up to throw when I mention bringing the standing throw position into the full throw. Nothing could be further from the truth. How can throwers bring the natural standing throw position into their full throws and in so doing maximize power in their full throws? It is actually pretty simple on paper to explain, much more difficult to put into practice. Please consider the following closely. The coach and thrower may even wonder if it is possible to pull the discus around from such an extended and protracted point. The answer is yes. With considerable practice your thrower can achieve what I call an exaggerated J- Sweep. It is the very reason we observed such an increased length of pull for Cole. Some of my coaching peers commented at meets that James looked so calm in the center of the ring and wished their throwers could do the same. I would observe that it was merely an extended focal point with an additional twist of the torso, not so unlike Discobolus or a standing throw. And even if you cannot achieve the exaggerated length of pull Cole managed to achieve, any additional twist, even if it is only a couple inches, will move the discus significantly farther back. When your thrower succeeds in capturing this position, a commensurate increase in angular velocity and speed of release will follow. The throwers who do not acquire this position will, in my estimation, be leading with their heads and their upper bodies in their full throw and unfortunately have many missed opportunities. I have often been asked why I made such a dramatic career change from art/art history to coaching. To me the two disciplines have always been and will always remain inextricably tied together. Whether coaches realize it or not they, like Myron, are sculptors in their own right; shaping, and molding the thrower - technically adding a little here and taking away a little there as they search for the perfect throw. In the final analysis it is a search, so eloquently represented in Myron's Discobolus, that requires, much like the Greeks, both a scientific and an artistic awareness.

The coach and thrower may even wonder if it is possible to pull the discus around from such an extended and protracted point. The answer is yes. With considerable practice your thrower can achieve what I call an exaggerated J- Sweep. It is the very reason we observed such an increased length of pull for Cole. Some of my coaching peers commented at meets that James looked so calm in the center of the ring and wished their throwers could do the same. I would observe that it was merely an extended focal point with an additional twist of the torso, not so unlike Discobolus or a standing throw. And even if you cannot achieve the exaggerated length of pull Cole managed to achieve, any additional twist, even if it is only a couple inches, will move the discus significantly farther back. When your thrower succeeds in capturing this position, a commensurate increase in angular velocity and speed of release will follow. The throwers who do not acquire this position will, in my estimation, be leading with their heads and their upper bodies in their full throw and unfortunately have many missed opportunities. I have often been asked why I made such a dramatic career change from art/art history to coaching. To me the two disciplines have always been and will always remain inextricably tied together. Whether coaches realize it or not they, like Myron, are sculptors in their own right; shaping, and molding the thrower - technically adding a little here and taking away a little there as they search for the perfect throw. In the final analysis it is a search, so eloquently represented in Myron's Discobolus, that requires, much like the Greeks, both a scientific and an artistic awareness.