|

By: Chris McGown - Gold Medal Squared Originally Published in: Coaching Volleyball Copyright and Provided by: American Volleyball Coaches Association

Team defensive systems is one of the most explored topics in all of volleyball coaching. On the various coaching staffs of which I've been part, it was a subject that was high on our list of priorities - one that is accorded a large percentage of attention and time, both in theoretical development as well as practice on the court. We modern coaches have more tools available than our predecessors, but that hasn't made our decisions on systems easier. With the proliferation of video, there are more and more ways to watch and compare what other teams are doing across every level of the game. The availability, use and popularity of data has increased dramatically as well, creating an almost overwhelming amount of information that must be vetted, categorized, interpreted, analyzed and implemented. Given the challenges of abundance when it comes to our choices, how can we make the best decisions for our team? At Gold Medal Squared, we advocate strongly for two foundations in any decision-making process: principles and simplicity. In essence, what are the principles that underlie this system/skill/process, and how can we most simply implement those principles? It should be noted that in this article we'll focus mainly on back-row defenders - the blocking element of the system will be discussed in a future article. PRINCIPLES When dissecting a defensive system, we believe there are four main principles:

Let's take a look at these, with the understanding that we're looking to implement the simplest application of each principle. 1. Put your best defenders where most of the balls are attacked. This principle requires that we know the answer to two important questions: who are our best defenders, and where are most of the balls attacked? Who? The answer to the first question depends on the athletes in your gym and their respective capabilities. Here are some measures you might want to consider when answering the question of "who is my best defender?", in order of increasing complexity.

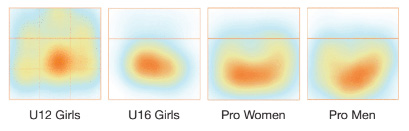

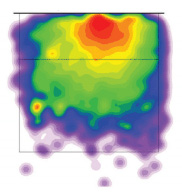

You may be inclined to continue to break this down further by where the attacks come from, what type of attack (hard driven, roll shot, tip, block deflection), rotation, etc. I find that most of these details get smoothed out and accounted for in a large enough data set. In other words, there's a strong correlation between the answer to the most-simple question (who has the most digs?) and the most complex question you can conceive. How far into this you want to go depends on your level, the time you have and the quality of your data. Where? The next big question to answer is "where are balls being attacked?" To get a sense of this, let's take a look at some heat maps of attack patterns from various levels. The way these charts were composed is that a dot was placed on the court where a player should be standing to dig the attack, waist-high, on their midline. If the balls were deflected off the block, we counted where the ball actually ended up. The more highly concentrated the dots, the "warmer" it appears on the map.

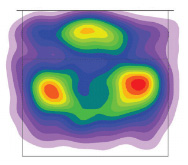

The similarity in these charts surprises some coaches. What we find is that volleyball, at every level, by both sexes, is highly patterned when it comes to attack. We've looked at various versions of this type of chart for over three decades, and the trends haven't changed. While there are nuances, the answer to the question of "where does the ball go?" tends to be "in the center of the court, about 6m deep. We've come to call that spot "Middle-Middle." This term is a visual reference for players, because they stand in-between the two sidelines, and in-between the 3m line and the baseline - the middle of the backcourt. Players understand a visual reference better than a numerical description such as "6m deep." There's a sub-principle at work here, in that as the game gets more powerful as the depth of attack gets deeper, but you'll find that this difference in-depth is subtle. The U12 girls team might play a step up from middle-middle, while the professional men might be a step or two back from middle-middle. Now you may be saying to yourself, "That doesn't look like my opponents at my level – this can't be right." My father, when faced with this question over the years, used to like to respond in his inimitable style by saying "Well, we've made our charts - make your own damn chart!" He'd say it with a smile, but would always tell coaches to send him their chart when they'd made one. Invariably, their charts would end up looking a lot like the ones above. We'd encourage you to examine the answers to these questions for yourself. Where do balls get attacked at your level, by your opponents? We'd be very surprised if the answer wasn't something very close to middle-middle. 2. Start your defenders where the ball will be attacked most quickly. We want to put our defenders where most of the balls will be attacked, but we want to start them where things will happen the fastest. If a player doesn't have time to move their feet in response to the set, we simply want them to be standing in the path of the attacked ball. Where do quick attacks happen? See the chart to the right from women's volleyball in the SEC conference - again this chart looks very similar across levels and gender. We find that a lot of quick attacks from the middle are hit about 5m deep (2m behind the 3m line), and 2m in from the sideline. This spot changes based on level and opponent capability (lower-level players tip more), but a good starting place is what we call "2 by 2," two steps into the court, two steps back from the 3m line. Note that there are two instances in which the ball comes over faster than a hitter attack. At the U12-14 level, you'll see a lot of overpasses, so account for that. Also, certain opponents may have a setter that likes to dump the ball, so your positioning might change based on that opponent trend. 3. The system should encourage players to read and react. "Simple, clear principles give rise to complex and intelligent behavior. Complex rules and regulations give rise to simple and stupid behavior" - Dee Hock, Founder, Visa Corporation We think the above quote captures the essence of good defenders in good systems. They have been taught simple, clear principles, and are now liberated within their system to play with intelligent and nuanced responses. We find that players that are given overly complex rules, or have been told their whole playing lives to "do X if Y," respond in ways that seem quite stupid when looking at the larger whole. They follow rigid rules rather than operate independently based on what is required by the play. Ron Larsen, former assistant coach with the USA Men's Gold Medal-winning 2008 team, says that "reading the game is the premier defensive skill." From a neuroscience perspective, these are the players that have superior pattern-recognition development - their physical responses happen much faster because their brains are operating without a series of rules and regulations that have to be processed. They are operating based on learned experience that manifests itself as instinctual. When we are teaching players to read, we start by having them attend to the factors that most influence where the ball will be attacked. We think there are two main ones, and three subsidiaries:

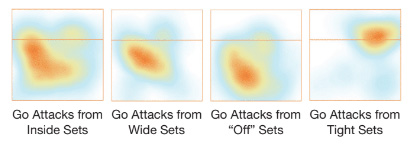

The set. The single biggest factor on where the ball will be at-tacked is where the set took the hitter. Let's reference the charts below of left-side attacks from Pac-12 women's volleyball.

Note how strongly the set location influences the attack location. These charts are from highly skilled players, with refined abilities and athleticism, and they still are constrained by the set. Inside sets and wide sets (even with or past the antenna) are hit in the angle. Sets off the net are hit towards the corner, and tight sets are tipped short. When the ball is set perfectly, hitters have their full range of options. The first thing we want our defenders to start to consider is, "where is this set taking the hitter?" For our beginning players, those reads won't be very good and they'll be slow; over time they'll come to get a feeling for where the set is headed and what kind of attack will come as a result. When teaching our athletes to read, a good first step is to let them watch the set long enough to know where it's going. Again, beginners will need longer looks than experts, but seeing and knowing where the set is taking the hitter is a critical foundation. This look is made even more important because of setter imprecision; the best setters in the world tend to locate the ball in the correct window only 55-65% of the time. This means the hitter will be constrained one way or another almost half the time.

The attacker's tendencies. The second biggest factor in where the ball will be attacked is the hitter's tendencies. What is their favorite shot, or what shot does their mechanics produce? In the case of a good set, where will they tend to hit the ball? Quite often at the younger levels, we'll see that the attacker will simply hit the ball the direction they are approaching (factor 3). We'll also see that they'll hit it towards the middle of the court because that increases the likelihood of the ball landing in. As the level of play gets better, players will attack the edges of the court more often, but even the most accomplished players have tendencies - oftentimes they are very highly patterned. The attacker's approach. We'd like our defenders to have a sense of the attacker's approach. It's unlikely that they'll be able to get central focus on the entirety of the approach, but good players will get peripheral information, and often will be able to get good focus on the attacker during the end of the approach. We'd like to pick up direction (especially as the attacker jumps), but also quality; is the hitter in rhythm? Did they get a full jump? Did they have to slow down, or hesitate? Out-of-rhythm approaches almost always mean some type of off-speed shot. The attacker's arm swing. The next factor that influences where they ball will be attacked (also the next factor sequentially in the attack) is the arm swing. We'd like our defenders to see an early answer to this question: hit or tip? Will the attacker swing hard, or are they going off-speed? Arm position changes dramatically if I am attacking a ball vs. tipping a ball. Often this is the natural result of factors earlier in the sequence. Tight set? Hesitant approach? We should expect the arm to come up and extend for a tip If the attacker is hitting it hard, I like my defenders to see the general area of the shoulders and the head. If they try to focus on the hand or even the arm above the elbow, we find that those parts move too fast for the human eye to readily track, and they miss out on directional information. An analogy I like is that the end of the whip follows the handle of the whip, so see what the handle is doing because your eyes can follow that. The block. The factor that least influences where the ball will be attacked is the block. At lower levels, the block has almost no influence whatsoever. As the level gets higher the block has more significance, but even at the highest levels it still comes in last. What does this mean for our defenders? Two important things:

We do want our defenders to have a sense of what our block is doing, and good defenders will get good peripheral input about the block as they see the hitter. But the simple guidelines are "see the set, know the hitter, dig the ball." Are hitters affected by the block? Yes, but it happens too late for the defender to reliably use the information, and the best way to determine how the hitter is changing the shot is to see the hitter themselves! 4. Tactics should be based on trends. Within our defensive system, we'd like the flexibility to make some tactical choices that will shift us out of our defaults. However, we'd like to make these changes based on strong trends rather than a few outlier shots. Joe Trinsey of Gold Medal Squared teaches that we as humans are good at remembering all of the varieties of things that happen, but that we aren't very good at assessing the number of times each of those events occurs. We as coaches tend to think and respond irrationally when a tip falls, or a ball lands in the corner. Rather than consider these as outlier shots, we make adjustments that take us out of the high-percentage locations. So as part of your pre-match planning or in-match adjustments, be sure you are adjusting to established trends rather than isolated anomalies.

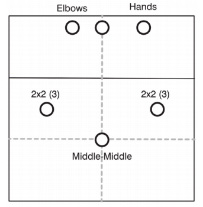

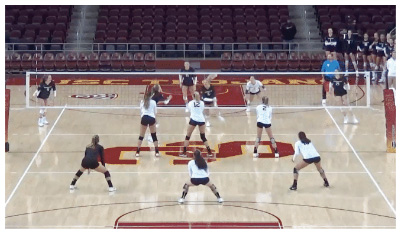

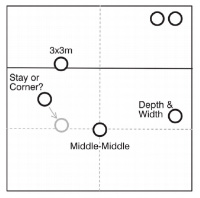

APPLICATION Base Defense. What does this system look like when put in practice? See the diagram and live example photo. We'll start our players in the positions we referenced earlier: middle-middle (middle-back), and 2x2 for our wing defenders (left-back, right-back). The 2x2 (3) refers to the fact that at some levels, you might start a meter/step deeper with your wing defenders based on opponent attack depth.

Let's take a look at two very common plays - a ball set to the opponent's left-side attacker (Z4), and then one set to the opponent's right-side attacker (Z2).

Left-side Attack. In our first scenario (opponent left-side attack), we see the following adjustment:

As far as the physical moves needed to make the above shifts, we like our players to get wherever they are going on the court with a three-step shuffle move. This allows them to stay square to the play and still cover the needed ground. We count shuffle steps when a foot touches the ground - for example, the player in the diagram (facing page) making a move to cut off the corner would shuffle-step right-left-right. Same with the off-blocker, and with the right-back line defender.

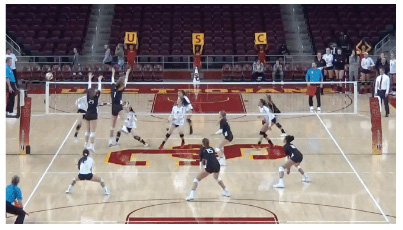

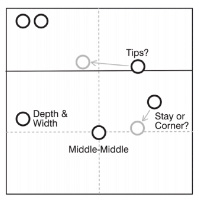

Right-side Attack. A ball set to the right-side attacker is almost a mirror image of a left-side attack with perhaps one exception.

I prefer our off-blocker to get some depth as they come off to cover the tips, and not to get right under the block. We want them to best be in a position to cover a variety of shots and still be able to go do their job as an attacker/setter. A good spot is somewhere just inside the 3m line, and just past half-court. See the diagram above. TRAINING THE SYSTEM A system is only as good as the players within the system - my experience is that great defensive teams always have a lot of great individual defenders. The two main qualities I like from my defenders are: They have a big defensive window. Too many players have holes in their defensive toolboxes, because they've never been asked to expand their abilities through long-term work. For example: "Oh, you can't get on the floor for a tip? Well, we'll just move you way up behind the block so you never have to get on the floor." Coaches are far too willing to make system adjustments based on player weaknesses rather than develop player skill. The first order of business is teaching our athletes a comprehensive defensive toolbox, and working with them consistently until they can defend a wide variety of opponent attacks with a refined set of defensive tools. We want each player on our team to have an ever-growing defensive range. They see the game well. My dad would say that "we need to teach our players to move, then we need to teach them to see." The early stages of player development emphasize movement skill (the toolbox), but our athletes really become great volleyball players when they can see the game well and gain the fractions of seconds needed to make the plays that separate elite players from average ones. So once your players have a sufficient level of skill, your coaching needs to emphasize what they see and how they move based on what they see. This means we need a practice environment that gives them a lot of opportunities to see game-speed play, and your feedback should focus on player vision. "What did you see there?" is a great question to ask, and allows for some dialogue and teaching. My experience has been that there are no shortcuts in this process; it requires time, commitment and patience from coach and athlete. This article only scratches the surface of this topic. I'd love to talk with you more about anything I've written here, and any other questions this article may have generated. Contact me at a Gold Medal Squared coaching clinic, or at info@goldmedalsquared.com. |

ably "should" be able to dig (at your level), and then make a subjective grade.

ably "should" be able to dig (at your level), and then make a subjective grade.