|

chapter from Coaching Volleyball Technical and Tactical Skills by Cecile Reynaud

Volleyball is the ultimate team sport. Players need to master many technical skills and know how to apply those skills in tactical situations. Most of the focus in team practices and individual training sessions is on the development and improvement of volleyball skills. Coaches, however, must also be concerned about objectively analyzing and evaluating those individual skills and using that information to develop the team's season and game plans. For example, decisions about starting lineups, having players specialize in certain positions, and developing offensive and defensive tactics can be made only if coaches have the necessary information to make sound decisions. In building a team, coaches should use specific and accurate evaluation tools to assess the development of the individual parts that make up the whole of the team. You must remember that basic physical skills contribute to the performance of the technical and tactical skills of volleyball. In addition, a vast array of nonphysical skills, such as mental capacity, communication skills, and character training, overlay athletic performance and affect its development and should also be considered (Rainer Martens, Successful Coaching, Third Edition, Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2004). But even though all these skills are important, the focus here is on evaluating the technical and tactical skills of volleyball. Please refer to Successful Coaching, Third Edition, to learn more about how to judge those other more intangible skills. In this chapter we examine evaluation guidelines, exploring the specific skills that should be evaluated and the tools to accomplish that evaluation. Evaluations as described in this chapter will help you produce critiques of your volleyball players that are more objective, something you should continually strive for. Guidelines for Evaluation o Understanding the purpose of evaluation

o Motivating for improvement o Providing objective measurement o Effectively providing feedback o Being credible

Motivating for Improvement The best motivation, though, is striving for a personal-best effort in physical skills testing or an improved score, compared with the last evaluation, on measurements of technical, tactical, communication, and mental skills. When an athlete compares herself today to herself yesterday, she can always succeed and make progress, regardless of the achievements of teammates. And when an athlete sees personal progress, she will be motivated to continue to practice and train. This concept, while focusing on the individual, does not conflict with the team concept. Rather, you can enhance team development by simply reminding the team that if every player gets better every day, the team will be getting better every day. Providing Objective Measurement Effectively Providing Feedback Being Credible Evaluating Skills As you evaluate your athletes, one concept is crucial: Each athlete should focus on improving her own previous performance as opposed to comparing her performance to that of teammates. Certainly, comparative data help an athlete see where she ranks on the team and among other players in the same position or role, and this data may motivate or help the athlete set goals. However, all rankings will place some athletes on the team below others, and the danger of focusing solely on this type of evaluation system is that athletes can easily become discouraged if they consistently rank in the bottom of the team or position. Conversely, if the focus of the evaluation is for every player to improve, compared with personal scores at the last testing, then every player on the team has the opportunity to be successful. Whether you are looking at physical skills or nonphysical skills, encourage your athletes to achieve their own personal bests every time they are tested or evaluated. Testing should occur at least three times a year—once immediately before the volleyball season begins to gauge the athletes' readiness for the season and provide an initial or baseline score; once at the end of the season to measure the retention of physical skills during competition; and once in the off-season to evaluate the athletes' progress and development in the off-season program. You will be constantly evaluating your athletes throughout the season to make slight adjustments as needed. Of course, training programs can positively affect several skills. For example, improvements in leg strength and flexibility will almost certainly improve speed. Furthermore, no specific workout program will ensure gains for every athlete in each of the six skill areas. Consequently, measurement of gains in these areas is critical for showing you and the individual athletes where they are making gains and where to place the emphasis of subsequent training programs. To test upper-body strength, the athlete can perform a two-hand basketball chest throw. The athlete stands at a line and chest-passes the basketball as far as possible along a tape measure stretched out in front on the floor. Make sure someone is standing alongside the tape measure to see or mark where the ball lands so an accurate measurement can be taken. The athlete should repeat this for a total of three throws. Again, you may average the result for a score, or the best of the trials may be used. Athletes can also do a one-minute push-up test (complete full-body push-ups). Each athlete performs as many complete (in good form) push-ups as possible in one minute. A second and perhaps third trial may be done as well, with a rest period between. The same scoring options apply. Athletes will begin to appreciate the need for good overall strength as they get stronger and discover they have more control over what their bodies are doing. They will be able to move quicker, jump higher, and have more control over their skills as they play this fast-paced sport. They will be able to maintain their focus and control when matches last several hours. Core Strength The core must also be strong for volleyball athletes to play with great explosive-ness—combining strength, power, and speed into serving, attacking, and blocking. Every physical training program for volleyball, therefore, must include exercises that strengthen and develop the core. This training program must go beyond sit ups and crunches, which are important but not comprehensive enough to develop true core strength. Volleyball athletes must incorporate active exercises such as lunges, step-ups, and jump squats to focus on development of the core. Implements such as weighted medicine balls, stability balls, and resistance bands may be incorporated into the training program as well. Speed Even though the volleyball court is a small area relative to some other sports courts, it is critical that athletes achieve maximum speed in their movement on the court. Players may have to run down an errant pass, move quickly to pass a hard serve, or use quick footwork to move to block or hit a slide. Players can spend a lot of time training in other areas, but they need to know that their overall success as volleyball players will depend on how fast they can move their bodies from point A to point B. Agility In many situations in the sport of volleyball, players must maintain a balanced body position but still be able to quickly change direction on the court. A player in the back row playing defense will need to be ready to chase a deflected ball hit off a blocker's hands as well as move to a ball that hits the net, which changes the anticipated flight of the ball. Power For the vertical jump, place a tape measure up the wall vertically. The athlete stands with her side to the wall, both feet flat on the ground, and reaches up with the hand closest to the wall. The point of the fingertips is marked or recorded. This is called standing reach height. The athlete then stands slightly away from the wall and jumps vertically as high as possible from a standing start, using both the arms and legs to assist in projecting the body upward. The athlete attempts to touch the wall at the highest point of the jump and reach. The difference in distance between the standing reach height and the jump height is the score for the vertical jump. The best of three attempts is recorded. A Vertec is a good piece of freestanding equipment to measure the vertical jump with the most accuracy. Since the sport of volleyball is played over a net set at a certain height, it is essential that athletes use the power in their legs to elevate their bodies off the floor so they can attack the volleyball at a higher contact point, therefore increasing their success rate of hitting the ball down into the opposing team's court. Being able to jump high to get their hands across the net to block balls hit by the opponent is also a highly desired skill. Flexibility Although volleyball players are mostly on their feet, they often need to extend their bodies to dig a ball or play a deflected ball. Good flexibility will help keep an athlete from sustaining injuries such as a strained groin or hamstring muscle and hopefully protect the joints from more serious injuries.

Despite the importance of the physical, mental, communication, and character skills, however, the emphasis in this book is on the coaching of essential technical and tactical skills. For an in-depth discussion of teaching and developing both physical and nonphysical skills, refer to chapters 9 through 12 in Rainer Martens' Successful Coaching, Third Edition. Mental Skills Most important to volleyball players' success, however, is the mental ability to understand the game and read cues that allow them to execute the proper skill at the right time. They must work hard on every point and continually monitor what is successful and not successful. Players must be ready to adapt to what their opponents are doing offensively and defensively. A consistent performance of technical skills requires knowledge of the game, discipline, and focus on the right cues while maintaining composure as a team. The term mental toughness might be the best and simplest way to describe the concentration and determination required to effectively execute the technical skills and appropriate tactical skills in the course of a long volleyball match. Communication Skills Character Skills Evaluation Tools You can use many different systems to evaluate what you see on video. The most common system isn't really a system at all—it is the subjective impression you get when you watch the video, without taking notes or systematically evaluating every player on every play Because of limitations of time and staff, many coaches use video in this manner, previewing the video, gathering impressions, and then sharing those impressions with the player or players as they watch the video together immediately at courtside or at a later time. Many coaches, depending on the level of play, have video and computer software that systematically breaks down the video by skills, players, certain rotations, plays, and any number of criteria a coach is interested in. The focus can be on specific techniques and tactical decisions by the players. The grading process can be simple; for example, you can simply give the athlete a plus or a minus on each play and score the total number of plusses versus the total number of minuses for the game. Alternatively, you can score the athlete on each aspect of the play, giving her a grade for technique and a grade for her tactical decision making. More elaborate grading systems keep track of position-specific statistics. Regardless of the level of sophistication or detail of the grading instrument, most coaches use a statistical system of some kind for evaluating player and team performance. Most grading systems are based on a play-by-play (or rep-by-rep in practices) analysis of performance, possibly coupled with an analysis of actual practice or match productivity totals such as the ones listed previously. Here are some basic statistics you may want to keep on your players, either individually or as a team:

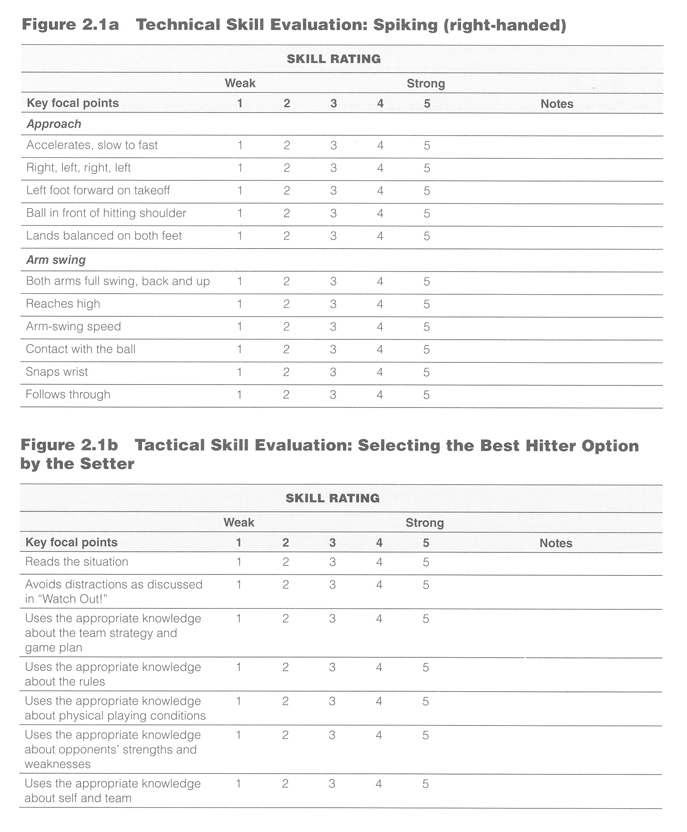

As you may already know, evaluating tactical skills is more difficult because there are many outside influences that factor into how and when the skill comes into play. However, as a coach, you can use a similar format to evaluate your players' execution of tactical skills. You will need to do the legwork in breaking down the skill into targeted areas; in figure 2.1b, we have used a generic format to show you how you can break tactical skills down for the setter using the skills found in chapters 5 and 6 as a guideline. The sample evaluation tool shown in figure 2.1, a and b, constitutes a simple way to use the details of each technical and tactical skill, providing an outline for both the player and coach to review and a mechanism for understanding the areas in which improvement is needed. The tool can also be used as a summary exercise. After a match, after a week of practice, or after a preseason or spring practice session, an athlete can score herself on all her essential technical and tactical skills, including all the cues and focal points, and on as many of the corollary skills as desired. You can also score the athlete and then compare the two scoresheets. The ensuing discussion will provide both the player and you with a direction for future practices and drills and will help you decide where the immediate focus of attention needs to be for the athlete to improve her performance. You can repeat this process later so that the athlete can look for improvement in the areas where she has been concentrating her workouts. As the process unfolds, a better consensus between the athlete's scoresheet and your scoresheet should occur. You must evaluate athletes in many areas and in many ways. This process of teaching, analyzing, evaluating, and motivating an athlete to improve her performance defines the job of the coach: taking the athlete somewhere she could not get to by herself. Without you, the athlete would not have a clear direction of the steps that need to be taken or how to proceed to become a better player. The coach provides the expertise, guidance, and incentive for the athlete to make progress. The evaluation of the athlete's technique might be substantially critical. You need to be careful how criticism is presented, however, and avoid purely negative comments. Try to catch your athletes doing the skills correctly as much as possible and give feedback on that basis. One final rule, however, caps the discussion of evaluating athletes. Athletes in every sport and every age group want to know how much you care before they care how much you know. You need to keep in mind that at times you must suspend the process of teaching and evaluating to deal with an athlete as a person. You must spend time with your athletes discussing topics other than their sport and their performance. You must show each athlete that you have an interest and a concern for her as a person, that you are willing to listen to each athlete's issues, and that you are willing to assist if doing so is legal and the athlete wishes to be helped. Events in an athlete's personal life can overshadow her athletic quests, and you must be sensitive to that reality. You need to make time to get to know your players as people first and athletes second. Athletes will play their best and their hardest for a coach who cares. Their skills will improve, and their performance will improve, because they want to reward the coach's caring attitude for them with inspired performance. They will finish their athletic careers for that coach having learned a lifelong lesson that care and concern are as important as any skill in the game of volleyball. |

|

|