|

By: USA Volleyball Originally Published in: Volleyball Systems and Strategies Provided by: Human Kinetics

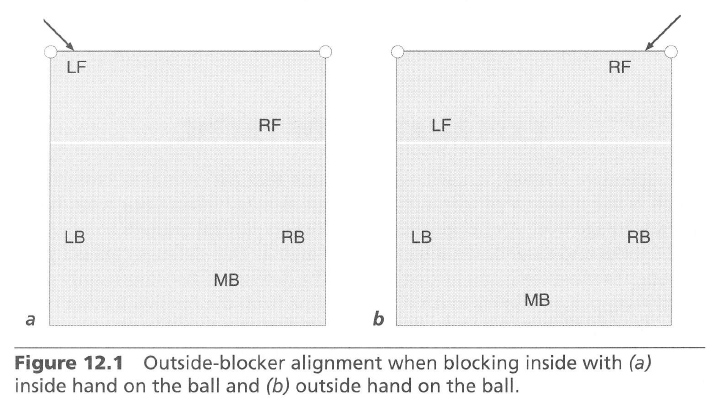

EXPLANATION OF TACTIC This defensive strategy is used against teams that hit primarily crosscourt, which is the majority of teams. Choose this strategy when your team has a size advantage over your opponent and blockers skillful enough to generate stuff-blocks and slow down a hard-driven attack. This defense cuts off your opponent's most common hitting angles. The defense is also commonly used to invite opponents to try to hit down the line from the outside hitting positions, forcing them to hit shots they are likely less comfortable with (because they haven't trained it in practice and also because there's less space to hit the ball into) and which ideally result in unforced errors. This defensive strategy also makes it easier for diggers to dig because balls hit down the line generally aren't as powerful as crosscourt shots. Although this strategy is designed for defending an opponent's outside attack, it can also be used in defending a middle attack. In this case, the middle blocker would take away the ball that the opposing middle hitter would hit to the left or middle back, coaxing the hitter to turn and hit to your right- back digger, which is a cut-back ball that's more difficult to hit with accuracy. Middle hitters generally are used to hitting to the left- and middle-back areas because that is where they face on their approach, so this strategy takes them out of their comfort zone. Contrary to blocking the line and digging inside (chapter 11), which requires strong diggers, this defense requires strong blockers. Within this defensive strategy your Mockers have greater flexibility in positioning for the inside (or crosscourt) block inside the antenna. For instance, giving your blockers the latitude to move their feet significantly inside the antenna (by as much as 4 feet, or 1.2 meters) should pay off in terms of the number of stuff-blocks they can collect. In executing the inside block for the crosscourt shot, some outside blockers choose to set the block with their inside arm at the point where the ball will cross over the net and the other arm outside (figure 12.1a) to still have a chance for a stuff-block while protecting some line as well. This also is an alignment that allows the middle blocker to close to that position with her outside hand and take away more of the crosscourt angle. At other times, the outside blocker will place the outside hand where the ball will cross the net, effectively sealing off any opportunity for the hitter to hit strong crosscourt with success especially if joined by the middle blocker, but completely giving up the line or cut-back shot (figure 12.1b). Still other times the outside blocker will choose to split the difference, basically lining up with his or her head on the point of contact so one hand is inside and the other outside that point, protecting against both shots equally. If unsure of hitter tendencies or if blocking one on one, sometimes this is the smart alignment to start with.

The first alignment discussed is used when the outside blocker is a single blocker, and the second is used more if the single blocker is your middle blocker since this alignment requires less movement. If forming a double block the outside blocker would assume the first position to set the block and the middle blocker moves to the second position.

The positioning of your crosscourt diggers in the defense will depend on where and how your blockers set up. For instance, if the outside blocker chooses to block with arms splitting the difference (as shown in figure 12.1), crosscourt diggers will flood the zone to defend balls that get past the block. If blockers block with their outside hand on the ball, which moves them inside the court even more, this will cover significantly more of the zone area, so diggers likely won't need to flood the zone. In this case, the crosscourt digger reads, anticipates, and digs balls that come crosscourt, whereas the middle-back digger reads and anticipates as well but tends to stay closer to the middle-back position, allowing the backcourt diggers to be equally balanced. PERSONNEL REQUIREMENTS As mentioned, the primary personnel requirement for this defense is strong blockers–at least two of them. If your team has stronger diggers than block-ers, you'll want to choose another defense, such as the block-the-line-and-dig-inside defense discussed in chapter 11, which has the blocker channeling the ball to strong diggers. If you have two strong blockers and then a significant drop-off in skilled blockers after that, try to put your two strong blockers in opposite positions within the rotation. The benefits of doing so are obvious (you'll always have a strong blocker in the front row), but sometimes it's not feasible. In general, you'll always want to have your two best hitters playing in opposite positions, and if one of those is also one of your best blockers, sometimes this means your two best blockers can't be opposite of each other. If your two best blockers aren't opposite, you need a third blocker who can play within the defense (i.e., he or she must be able to block hard-driven crosscourt swings). If your team doesn't have such a player, he or she will need to be developed through training. In earlier chapters we've discussed the impact that effective reading, anticipating, judging, and timing can have for your team. Good skills in these areas are always useful, but they are crucial for a team using a strategy geared toward blocking an aggressive crosscourt attack, even more so if choosing to block with only one blocker. A player who struggles in only one of these perceptual skills will have trouble being an effective blocker. In general in this system, diggers need competent but not excellent skills. But because outside blockers will sometimes move the block 4 to 5 feet (1.2- 1.5 meters) inside the antenna to take away the crosscourt attack, a sizable opening is often left for hitters to attack the line. The line digger must be able to retract quickly from base position and get back to a court position deep enough to dig the hard-driven attack while maintaining a body position that allows for forward movement. The line digger must also have quick reactions, ready to stand in the line of fire when the block adjusts and an outside hitter spots the opening between the blocker and the antenna. This ball will pr ob-ably not be blocked or slowed down by the blocker, giving the digger full responsibility to keep the ball in play. And if it is touched by the blocker, it may deflect out of bounds, which then requires the digger to be fleet enough of foot to react and run it down. ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES As mentioned earlier, the primary advantage of this defensive strategy is that it takes hitters out of their comfort zones. Their favorite shot is either taken away or must be adjusted to challenge the block. A particularly strong attacker will be able to excel even against this defense, because they'll beat the block more often than not, but such attackers are rare. As you recall, generally speaking, the less blockers and diggers must alter their position in order to make a play, the more success they'll have. In this defense, because they know they'll be blocking some portion of the crosscourt, blockers can establish an initial base position closer to that possible shot so that movement demands are minimal, allowing them to focus more fully on the hitter. The main disadvantage of this defense is revealed against teams with dominant attackers who can hit down the line effectively (exclusively one line or the other, or angle or line at will). Teams who choose to block inside against such teams do so because they haven't scouted their opponent well enough, or because they believe their diggers will be up to the task of digging many hard-driven balls down the line. Such teams might be fooling themselves, however, because even the best diggers will have trouble digging these shots consistently. Another disadvantage of this system is the amount of time a line digger has to respond to the ball. Because the line ball travels less distance, a hard-driven ball gets to the line digger faster than a hard-driven ball hit crosscourt. You hear players and coaches speak of the benefits of "slowing the game down." Well, that doesn't happen here. The hard-driven ball can come like a rocket at the line digger, and only the best diggers can handle such a ball. One last thing to consider: If you play a defensive system in which your setter plays defense in the right-back position, blocking crosscourt leaves the setter exposed to taking the first contact more often, resulting in the setter being unable to run the transition offense to his or her hitters. OPTIONS Options in this defense depend largely on the blockers because diggers will react to what the blockers choose to do. When a blocker sets the block farther into the court, the farther up the line the digger should move, while continuing to hug the line. Because the block in this situation is set up to defend the crosscourt attack, any shot down the line will clear the net and tend to travel in a downward trajectory. Conversely, the farther outside the block is set (i.e., the closer the outside blocker's outside hand gets to the antenna), the deeper the line digger stays, recognizing that balls hit down the line will either be blocked, will deflect off the block, or be hit high over the block sending the ball deeper into the court. An exception to this rule is when the digger is confident the hitter won't try to hit down the line at all because the blocker is completely taking away that shot; in this situation, the line digger will read, anticipate, release, and move forward to defend a tip that goes down the line. Similarly, crosscourt diggers will also be heavily influenced by blockers in this defense, often sacrificing a clear vision of the ball to allow themselves room enough to play the ball. In general, left- and right-back diggers should line up shoulder to shoulder with the inside blocker's inside shoulder, in such a position that if the digger ran forward toward the blocker, she would in effect line up as the third blocker. Diggers who need to constantly reposition to fully see the ball might put themselves out of position to play the ball well. Crosscourt diggers must remain alert and focused, but also ready for balls to come at them seemingly out of nowhere if the blocker has blocked their view. COACHING POINTS Coaches choose this defense when they know their blockers are capable of defending shots hit by talented crosscourt attackers. We've discussed earlier the skills associated with effective blocking (reading, anticipating, judging, and timing). In drills, ask your blockers how they determined where they ended up jumping from based on what they were watching. Many times your blockers won't know what led them to jump from a particular spot, which tells you they weren't doing much thinking or observing what the hitter was doing. If a player says, "I don't know," ask him or her to perform a few more reps, and then ask the question again. Be assured that during follow-up repetitions, your blockers will pay greater attention to the hitter's approach angle, speed, hips, eyes, and shoulders, allowing them to be more efficient blockers by becoming better observers. If you have utmost trust in the blocker setting the block (typically the outside blocker in the two-blocker system), give this player leeway to establish the position from which the block will jump. Players see many different things on the court that are harder to see as a coach on the sideline. (This is a good reason that when coaching blockers, coaches should be on the court either behind the blockers or across the net in front of them to see what they are seeing and help give them the proper cues about what to look for.) If a player communicates to you that he or she feels a ball is going to be set to the left- side hitter and that the hitter is going to try to attack the line, this might be a time to trust your blocker and allow him or her to block the line, although the strategy by and large is to block inside. Trust your players–until they give you reason not to. Coaching points for the back-row diggers involve the same principle as just described for blockers–give your diggers opportunities to observe game-like hitters, and train them to move to areas without infringing on someone else's territory in order to dig a ball. There will be times when diggers move to a position you instructed them to move to, only to see the ball hit elsewhere. Sometimes a digger will not possess the sense of responsibility needed in order to chase down this ball. You and your team work hard at teaching efficient movements and reading to your diggers, but ultimately, if the ball is hit somewhere else, the digger is still responsible for doing what it takes to keep the ball in play. Instill in your diggers the attitude of relentless pursuit of every ball. Don't allow them to decide whether or not a ball can be dug. Every ball should automatically be pursued until it hits the floor.

|