|

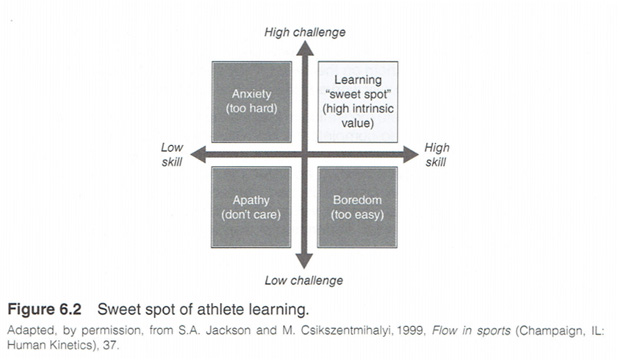

By: Wade Gilbert Originally Published in: Coaching Better Every Season Provided by: Human Kinetics Effective coaches devote considerable time to identifying and creating training activities for their athletes. But even the most creative and engaging learning activities will miss the mark if coaches do not also consider the influence of their athletes' motivation to engage in the learning experience. Athlete motivation determines the intensity, persistence, and quality of their learning efforts. Two primary drivers create athlete motivation to learn. The first driver is the subjective value that athletes place on the goal of the learning activity, sometimes referred to as goal importance. Coaches should not assume that their athletes will automatically see the relevance of learning goals or training activities. Coaches need to offer a clear explanation of not only the what of learning goals and practice activities but also the why. Research and feedback from athletes show the value of providing athletes with the rationale for selecting a particular approach to practicing a skill. For example, in the weeks leading up to the 2015 Super Bowl, athletes playing on the New England Patriots, the team that eventually won the championship, explained why they liked playing for renowned football coach Bill Belichick: He has always backed his arguments up - by arguments. I mean what he's trying to coach and teach you. I think anyone that's coaching, you shouldn't have to take them on their word. They should be able to point to you where it has actually worked, where it has been effective. The second driver of athlete motivation to learn is the beliefs, or expectancies, they hold about their ability to complete the learning activity. Coaches can help athletes see the value in their training activities and increase their expectancy of skill mastery by connecting training activities to one or more common value sources: attainment value, intrinsic value, and instrumental value. The first value source is attainment value, which refers to the personal satisfaction that an athlete feels when performing or learning a skill. The need to feel competent and learn how to navigate our environment successfully is a basic human need. A simple way to help athletes fulfill their attainment value is to start each practice session with activities that have a high success rate. For example, the coach can start each practice by repeating an activity that the athletes have successfully performed in the past. A good approach is to select a short activity that will ideally also serve as a dynamic physical and mental warm-up, thereby increasing the efficiency of time use and increasing athletes' readiness to learn new skills. Then, each practice session can end with a more challenging activity that is perhaps just beyond the reach of most of the athletes. This activity can be repeated at the end of each practice until all or most of the athletes can complete it successfully. This approach to starting and ending each practice session with challenging, yet possible, activities will promote athletes' sense of attainment. The second value source is intrinsic value, sometimes also referred to as intrinsic motivation. Intrinsic value can be increased by creating practice activities that allow athletes to experience the joy of training and reconnect them with their love for the sport. Moments when athletes lose themselves in the activity because of the high intrinsic value attached to it are often described as being in the zone or flow experiences. Although there are multiple components and sources of flow, challenge-skill balance has been identified as the golden rule of flow. Challenge-skill balance refers to the match between an athlete's current skill level and the difficulty of the task. If athletes perceive the task to be too far beyond their current skill level, they will approach it with low intrinsic value. In their mind it is too hard and not worth trying to attain, which can lead to anxiety. On the other hand, if athletes perceive the task to be too far below what they are capable of doing, they will also approach it with low intrinsic value. In these situations the task is perceived as too easy and again not worth the time and effort, leading to boredom or apathy. The goal for coaches is to create learning activities that are just beyond the athletes' current skill level but are perceived by the athletes to be at least within reach. These types of activities hit the sweet spot of athlete learning and offer the greatest chance of allowing athletes to experience moments of flow and nurture the intrinsic value they will attach to the training activity (see figure 6.2).

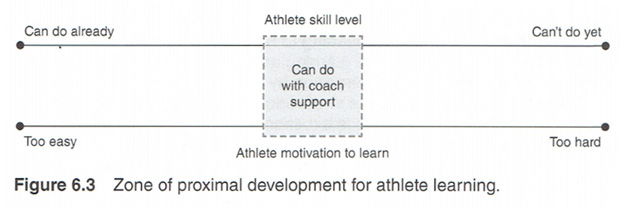

These learning sweet spots are also commonly referred to as zones of proximal development, a widely influential learning concept first coined by psychologist Lev Vygotsky in the early 20th century. Skill improvement will be greatest when coaches can create learning activities that are between what the athletes can already do without assistance and what they cannot do on their own. In other words, the difficulty of the learning task is proximal (close) to the athletes' current ability and the task can be successfully completed with appropriate support from the coach. The purpose of these learning zones is to provide athletes with guided opportunities for purposeful struggle that increase the rate of learning. The analogy of a slide ruler may be a useful way for coaches to think about how the zone of proximal development can be used to find the sweet spot of athlete skill level, athlete motivation, and coach support when designing learning activities (see figure 6.3). Much as the center portion of a slide ruler is moved back and forth to identify the correct response to a problem, effective coaches move the zone of proximal development back and forth for each athlete to create optimal learning experiences. The zone will need to be moved forward as the athlete masters a specific skill. The zone may need to be moved backward as the athlete attempts to learn a different skill or when an athlete is returning from injury or the off-season.

Coaches can find the appropriate challenge-skill balance, which naturally will fluctuate across a season and will vary with each athlete, by providing athletes with time to reflect during or after practices. Much can be learned simply by asking the athletes for their feedback on the degree of challenge and their perceived readiness to complete learning activities successfully. Many coaches hold group feedback sessions while athletes are gathered for their cool-down or stretching at the end of practices. Coaches can ask questions such as these: "What was the most valuable part of practice today?" and "What do you think we need to spend more time on in our next practice?" The third and final source of value for athlete learning is instrumental value, also referred to as extrinsic motivation. Athlete motivation to learn can be increased when coaches provide incentives, in the form of rewards, when athletes successfully complete learning activities. Some common types of extrinsic rewards used by coaches include recognition T-shirts, playing a game selected by the athletes, earning time off, or holding a team party. For example, Nell Fortner, Olympic championship women's basketball coach who also coached college and professional basketball, rewarded her professional athletes with a free pass from difficult conditioning drills if they could make 25 out of 25 free throws during a practice. Although this type of reward may be common and appropriate for professional athletes, more appropriate extrinsic rewards for youth, high school, or college athletes could include special recognitions for hardest worker or best teammate. For example, some coaches like to present athletes with a construction helmet for outstanding work ethic. Jon Gordon wrote a popular book on how a college lacrosse team used this strategy both to recognize athlete character and to honor a fallen teammate." The women's ice hockey team at Harvard also used the hard hat strategy to increase athlete extrinsic motivation. They award three distinctions following each game - a plastic hard hat for the hardest worker, a rubber duck for the top defender, and a feather boa for the top performer. Particularly noteworthy in the Harvard example is that the hard hat winner is selected by the previous winner as a way to increase the value that athletes place on the award. In addition, a sticker with the winner's jersey number is placed on the helmet each time it is awarded. I have witnessed this hard hat extrinsic motivation reward ritual in person in youth ice hockey settings as well. The effect of this simple strategy on athlete motivation was clear in the joy and pride expressed in the athletes' response after being selected to receive the hard hat. Another example of a coaching strategy used to reward and recognize athlete performance and increase the instrumental value that athletes place on learning comes from my work with a college basketball team. Given the popularity of superhero movies such as Avengers, Captain America, and Iron Man at the time when we were working together, the coach decided to use a superhero shield as a tool for recognizing athlete learning and performance. The coach purchased a replica of the shield used by Captain America. At the end of each week of practices, the coaching staff formally recognized the one athlete who best modeled the team's core values that week. Each athlete was also provided with a Captain America shield key chain to clip to his backpack. The key chain served as a constant visual reminder of the instrumental value of hard work and commitment to the team. For this type of instrumental value activity, coaches could also consider displaying their team's core values directly on the shield. Furthermore, each time an athlete is rewarded with the shield, a sticker with the athlete's jersey number could be added to the shield. At the end of the season the shield could then be prominently displayed in the team locker room to recognize that team's commitment to the core values and team work ethic. |