| Fist Motion Delay |

| By: Michael Holmes - UMPI

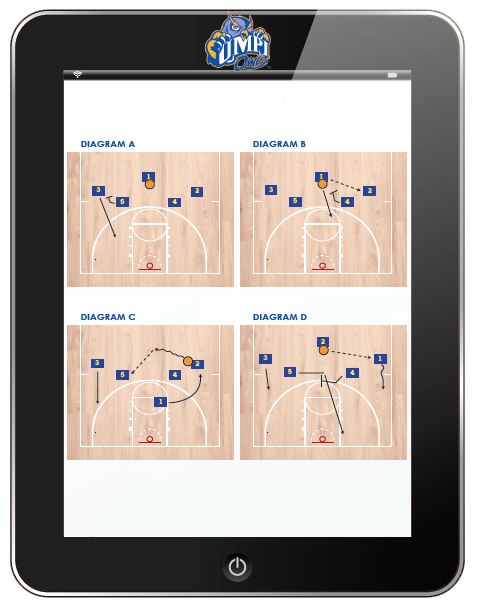

Originally Published in: Time-Out Magazine Provided by: National Association of Basketball Coaches With a shot-clock rule that rewards individual plays versus good team possessions, it is becoming gradually more difficult for "systems" to compensate for relative lack of athleticism; however, for those willing to undergo the sales pitch - we call it "brainwashing" here - to have players buy in, there are still methods for controlling the tempo of the game and giving less talented players the opportunity to be successful against more powerful rivals. We take our read-and-react motion game and extend it beyond the three-point arc. We call it Fist, and it is simply a 10-second delay series designed to make the defenders move, over-extend, and drop their mental defensive intensity. If we have a positive First series, there are two potential outcomes. The first one is that we get a back-cut or back-screen to free a player for a lay-in. If we have called Fist, we only allow our players to score on a lay-in from 30 seconds to 17 seconds on the shot clock. The second desirable outcome for Fist is ball possession. If the defenders soften pressure and allow us our cuts and screens, but take away the lay-up, we are still successful in controlling the tempo if we have possessed the ball for 13 seconds prior to engaging in our normal offensive attack. DIAGRAM A: The initial setup of Fist Motion Delay looks like this (we don't use a number system, but for the purpose of clarity we will number the players in a traditional manner). The reads are relatively simple for the first entry. 4 and 5 simply read the defending guard on their side. If the guard is above the offensive post (tight to the guard), the post should align himself to back-screen and release the overplayed guard. If the defending guard is below the post in a soft man, we know we will be able to enter the ball to the wing, so the post should begin to align himself for a back-screen on the point guard once the ball has been passed. DIAGRAM B: To keep the action moving, the receiving guard will dribble the ball back to the middle as the point guard fills his vacancy (we can screen him to get back to the spot if necessary). Ideally, we want the ball now to travel to the second side of the floor, with the weak side tandem now making the same reads as we did initially. However, let's assume that our dribbling guard decides to hit the post instead of the guard. In that case, we will make two basket cuts, up dribble our post, and keep the sequence going back to a third side as shown. DIAGRAM C: : When the shot clock reaches 17 seconds, it triggers our traditional motion series. At 17 seconds, we enter to the next side in sequence, and get a screen from the strong post at the top of the key for the weak post. While the cutting post will read this, in a majority of cases he will make a shuffle-type cut to the strong block, while our screening post pops to create a high-low relationship. DIAGRAM D: At this point, we have approximately 10-12 seconds to make two more quality screens and reads out of our motion set. We practice a great deal in the last ten seconds of the shot clock so that this play late in the clock will not cause anxiety. The quicker the movements in the delay portion of the possession, the greater the chance that the defenders will get "loose" in their weak-side help positions or in overplays of passing lanes. We do not use Fist Motion Delay all of the time, and if our match-ups are good enough, we may not use it at all in a game. It is, however, almost essential in the programs I have inherited to have some means available to shorten possessions, halves, or entire games to put our players in a position to have the best opportunity to win despite the size, skill, or speed discrepancies.

|