|

By: Bill Beswick Originally Published in: One Goal - The Mindset of Winning Soccer Teams Provided by: Human Kinetics Taking responsibility and accepting accountability should be woven into the fabric of any soccer club. The following elements are essential to this process.

1. Goals and Standards Coaches and players should collectively agree on team and individual goals and standards that are achievable and appropriate to the age and ability level of the players. Good communication at this stage is vital so that every player is clear on what is expected from her or him. Mike Krzyzewski, the head basketball coach at Duke University, is a coach from whom many soccer coaches can learn. His teams always demonstrate high standards: In putting together your standards, remember it is essential to involve your whole team. Standards are not rules issued by the Boss - they are a collective identity. Remember standards are the things you do all the time and the things for which you hold one another accountable. Involvement in many team sports besides soccer has confirmed to me that good coaches demand a small number of non-negotiables, universal standards that set the tone for individual and team accountability: timekeeping, appearance, courtesy and respect, commitment, attention, discipline and appropriate lifestyle choices. Beyond these, the team should ideally have involvement in agreeing goals and standards. 2. Reminders To help players remember their commitments, coaches need to find ways to integrate agreed goals and standards into the everyday life of the club. One coach I work with prints out the agreement and holds a buy-in ceremony (with pizza and parents present) where each player signs up to the commitment. These posters are displayed through the club. When players do not maintain standards, the coach merely has to take the poster into a team meeting and remind them what they signed up to do. 3. Culture Coaches should try to build a culture throughout the club, staff included, where accepting and taking responsibility is the norm. They should encourage everybody to help each other to meet goals and keep standards. Such a culture would emphasize purpose, standards, responsibility, commitment, flexibility and rewards. NFL coach Brian Billick (2001) stresses the link between accountability and integrity: On NFL teams that have integrity, players and coaches are compelled to take personal responsibility for a mistake they might have made in order not to let blame fall elsewhere. Such accountability is a sign of respect. It is a reflection of the team's integrity when individuals take responsibility for their actions. 4. Learning Environment Attaining goals and standards that have been set is a process that coaches teach and players learn. Every player on the team must be given maximum opportunity to learn and do his or her job to the required standard. Making a mistake, suffering a setback and not taking responsibility are useful teaching moments when real learning can take place. As experienced coaches recognize, teams often have to fail to succeed later. But continual failure to learn and adapt behavior has to be dealt with before it damages team progress. 5. Accepting Justified Criticism Coaches have to teach players to understand that a critical appraisal of their performance is honest and well-meaning feedback aimed at improvement. Although listening to the player is an essential part of feedback, coaches can use this opportunity to teach the difference between reasons and excuses. Before responding to any player's account of performance failure, a coach must determine which statements are valid reasons and which are simply excuses for not doing her or his job. Coach Anson Dorrance, who has an outstanding record in USA women's soccer (Dorrance and Nash 2014), points out that the differences men and women players often show when dealing with criticism: For men, you have to use videotape because they won't believe the criticism otherwise. With women, a video is more effective as a tool to show the positive aspects of performance and show them they played well. A lot of women don't have the confidence to feel they are as good as they actually are. It's not that you never show negative aspects of performance to women's teams, but seeing their mistakes on tape doesn't really help them. They believe you when you tell them they made a mistake. A video can almost make it worse because it magnifies the mistake. 6. Regular Feedback Ensuring a constant flow of accurate feedback so that full accountability for failing behavior on and off the field does not come as a surprise is another step in making a team accountable. Good coaches instinctively know when a player is struggling, and they should be proactive in confronting the player with early warning feedback, especially if their judgment is supported by performance data. Table 7.1 shows a list of simple performance measurements that can really help a coach in a player feedback session. At a professional level these measures are tracked objectively game by game to show variations in performance.

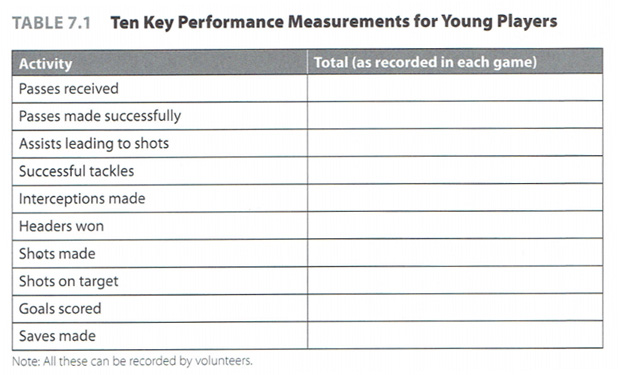

7. Thunderbolts Every team will face the occasional thunderbolt - a completely unexpected setback or defeat. Coaches should accept these happenings as abnormal and move on, not let them affect accountability nor allow them to undermine overall team progress. As soon as possible after such a game, although after emotions have settled down, the coach must switch the team mindset back to the bigger picture. Whilst acknowledging the disappointment of losing, here the coach has to recalibrate the mindset of the team; reaffirm the overall progress the team is making, change feelings from negative back to positive, and set up the expectation of success in the forthcoming games. As discussed in chapter 5, this step is important in building and maintaining good relationships. 8. Internal Challenge In an ideal competitive and accountable environment, teammates can feel safe to challenge each other when performance goals and standards are not being met. Peer group pressure is a powerful shaper of team and individual behavior. Players on championship teams hold each other accountable and don't wait for the coach to intervene. To maintain relationships, peer challenges should be given as positive statements of support - 'You are better than this', rather than the unhelpful, 'You are rubbish today'. 9. 'Can't Do' or 'Won't Do?' Before assessing accountability, coaches should ask whether failing behavior. is 'can't do', a physical or technical or tactical problem to be solved on the training ground, or 'won't do', an attitude problem to be resolved in discussion with coaches, parents or a sport psychologist. For example, I was asked to intervene with a fullback who was failing to make the runs required from defense to support the attack. I discovered that he was quite willing to do this but physically could not keep repeating these long runs. This was not a question of 'won't do' (he was willing) but 'can't do' (he needed better physical preparation). Coaches must ask and seek answers to this question before criticizing players. 10. Accountability Without Blame Coaches should ensure that any performance review and subsequent accountability are based on solid information and evidence, not an emotional•knee-jerk reaction to a particular incident. The coach must show emotional intelligence in making the review a learning experience that does not damage relationships (discussed more fully later in this chapter). The review should conclude with an agreed action plan to amend and improve performance, and the player should leave the review process in a stronger place mentally (see figure 7.1). |