| Direct and Indirect Free Kicks |

| By: Mark Berson

Originally Published in: Attacking Soccer - Provided by: Human Kinetics

I sat in a stadium during a prestigious youth soccer tournament watching an American team play in the featured match against an international side. Around me were a number of college head coaches and assistants. A free-kick situation unfolded, during which the American team produced an excellent opportunity to score. A young assistant next to me said, "Hey, they just ran our SMU play-that's unbelievable." That was interesting to me, because this young man only knew part of the story. The head coach of the club team who had initiated the free kick had sent a player to the University of South Carolina (USC), where he played for us for 4 years. This player introduced the same set piece to us, and we adopted it. The young assistant's head coach was my assistant at the time, and he took the same set piece to his college. The young assistant had not just witnessed a team copying his set piece but rather had seen the original play in action. In such a way, set pieces are witnessed by coaches, embedded in their memory, and then reshaped and retooled in order to meet the demands of each particular team. ATTACKING FREE KICKS The first order of business for the coach is to identify players within the team who may have special qualities enabling them to strike a ball accurately in a set-piece situation. One important quality to identify is the ability to bend a ball around or over a wall. Ideally, your team would feature a left-footed and a right-footed player with the same type of capabilities. Every effort should be made to identify these players and encourage them to further develop this set of skills. Repetition is critical here, and much of it will have to be carried out in individual work away from team training. Players should be encouraged to stay after training or come out on their own and work with the aid of an artificial wall and some goalkeepers in order to get the number of repetitions and quality of practice necessary to become proficient. It is ideal to have a good right-footed and a good left-footed player involved in each free-kick situation over the ball. This creates an unsettled picture for the goalkeeper, who might expect a bending or dipping ball from either player, freezing him in position and preventing him from anticipating the flight of the ball.

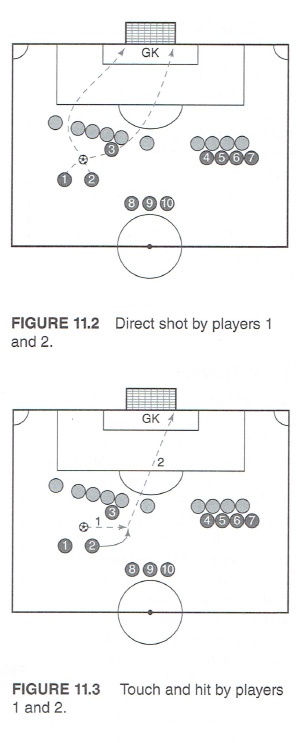

Taking these concepts into consideration, we have developed a set-piece alignment at USC and used it successfully for many years, creating many variations of it. The setup allows for a balanced approach with many options. See figure 11.1 for an example of this alignment. In this alignment, the space represented by the shaded area in the diagram is critical to the selection of the proper set piece. The closer the ball is positioned to the goal, the more important it is to get a shot or a one touch-and-hit shot off. These options include the following.

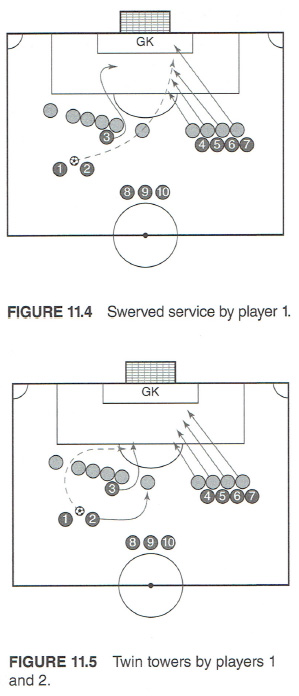

DIRECT SHOT The first option is a direct shot by player 1 (right footed) or player 2 (left footed). See figure 11.2. TOUCH AND HIT The second option is a touch and hit by player 1 and player 2 working together. See figure 11.3.

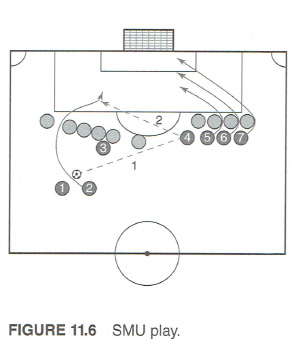

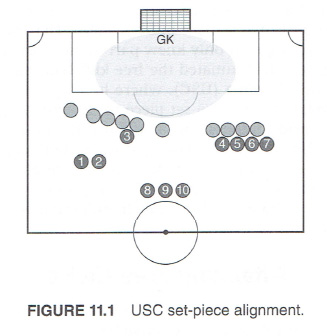

SWERVED SERVICE The next option is a swerved service by player 1 into players 4, 5, 6, and 7 for a direct header on goal. Player 3 spins around the wall in this option and positions for a ball headed back across the face of the goal. Because the goalkeeper will be pulled to the near post where the initial header should occur, the back-post area and player 3 may very well be open. See figure 11.4. TWIN TOWERS Another option is what we call the twin towers. In this option, player 2 and player 1 pretend to discuss their planned shot on goal. Player 2 moves away from the ball and player 1 moves up to apparently adjust the ball for his shot. In doing so, he places his toe under the ball and then lifts it over the wall to player 3, who has spun around the wall and into the space behind. Players 4, 5, 6, and 7 race into the attacking space for rebounds and to potentially finish up a ball that might be passed back across the face of the goal. Again, because the goalkeeper is pulled to the near post for the initial shot, the back-post area may well be open. SMU PLAY A final option is the previously mentioned SMU play. Here player 2 runs over the ball to the outside of the wall. Player 1 plays the ball to the feet of player 4, who has run across laterally, gaining just a step on the marker. Player 4 plays a one-touch ball into the space behind the wall for player 2. Players 4, 5, 6, and 7 go to seal off the back post for a ball that may be slipped across to them. Again, the goalkeeper may be pulled to the near-post shot or pulled out to cut the angle of the onrushing shooter and thus the back post may be wide open. See figure 11.6 for an example of the SMU play. We use a number of hand signals to signify which of the attacking options we will execute in each set piece. This enables all of the players to anticipate the attacking movement and perhaps pull a defender into a less optimal position in each case. For instance, they may check away from the area that they need to run into and then cut back suddenly to free themselves of their marker. In another instance, they may distract the defenders from the ball, enabling a more opportunistic shot on goal. In the attacking phase of our set pieces, we have the advantage of knowing exactly where the ball will go. We want to maximize that by dragging our opponents into the least favorable positions. |

Other specialists might include skilled headers of the ball, in many cases the center backs. They also need to spend extra time outside of team practice developing their timing and confidence in finishing chances that come to them.

Other specialists might include skilled headers of the ball, in many cases the center backs. They also need to spend extra time outside of team practice developing their timing and confidence in finishing chances that come to them.