|

By: Wade Gilbert Originally Published in: Coaching Better Every Season Provided by: Human Kinetics When coaches recognize their strengths, they build coaching confidence and mental toughness. The ability to overcome performance failures and emotionally difficult situations is a key characteristic of resilient coaches. For example, legendary soccer coach Sir Alex Ferguson attributed his long and decorated career to his resilience as a coach, something he developed first as an athlete: "The adversity gave me a sense of determination that has shaped my life. I made up my mind that I would never give in."

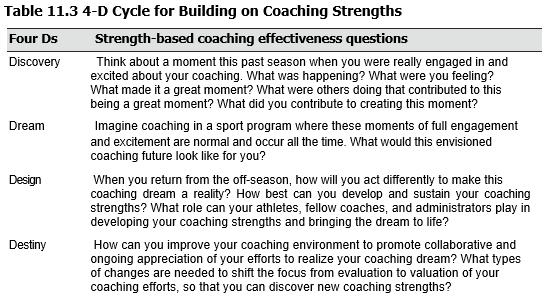

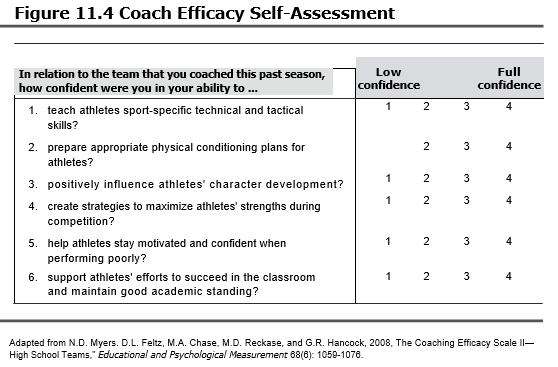

With ever-growing public scrutiny of coaches, the pressures that come with coaching will continue to mount. For coaches of high-performance teams in college and professional ranks, and increasingly in the high school and club sport levels, coaching tenures are highly unstable. For example, the normal tenure for professional sport coaches in the four major North American sport leagues ranges from a low of 2.5 years for the National Hockey League to a high of just 4.1 years for the National Football League. Many college coaches in high-profile sports such as American football fare even worse; one study showed that the average coaching tenure in one conference was only 2.3 years. Recognizing coaching strengths is a valuable exercise because it gives coaches confidence to enhance other areas of their coaching, something noted by championship coaches such as Augie Garrido: "Mastery in one area tends to help you focus on others, which is another reason to focus on developing strengths." Becoming a resilient coach requires self-confidence, sometimes referred to as coaching efficacy. Coaching efficacy can be separated into five dimensions, or areas, of coaching confidence: game strategy, motivation, technique, character building, and physical conditioning. Coaches' confidence in their decision making and ability to lead athletes and teams during competitive events is referred to as game strategy efficacy. When coaches believe they can help their athletes control their emotions, focus, and attitude, they are said to have high motivation coaching efficacy. The heart of coaching is teaching, and coaches who consider themselves good teachers of their sport exhibit technique coaching efficacy. The character-building aspect of coaching efficacy refers to coaches' belief in their ability to teach values, integrity, morals, and respect to their athletes. Finally, coaches must show confidence in their ability to structure appropriate strength and conditioning programs for their athletes, described as physical conditioning efficacy. Recently, some have called for the addition of a sixth type of coaching efficacy, labeled academic efficacy, for coaches who coach in school-based settings. Given that the mission of school-based athletics is to develop student-athletes who excel not only in their sport but also in the classroom, it makes sense that effective coaches would have confidence in their ability to help their athletes maintain academic eligibility and graduate. Several questionnaires have been created for coaches to identify their strengths by self-assessing their coaching efficacy. A simplified and adapted version of a coaching efficacy scale is provided in figure 11.4 as an example of a self-assessment tool to identify coaching strengths. Items on which the coach scores high (3s and 4s on the questionnaire) may be considered personal coaching strengths, and the coach should try to increase the use of those coaching behaviors. Coaches who have high coaching efficacy scores have been shown to have more effective teaching styles, more satisfied athletes, and better win-loss records than coaches who have low coaching efficacy scores. Furthermore, coaching efficacy appears to predict overall team efficacy, meaning that when coaches are confident in their abilities and maximize their strengths, their athletes also feel more confident in their abilities.

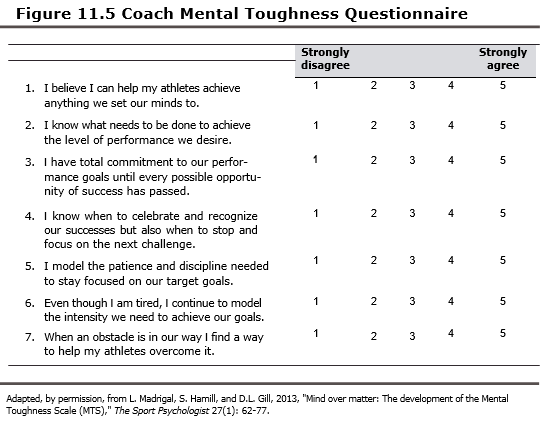

Not surprisingly, more experienced coaches typically report greater coaching efficacy than less experienced coaches do, but even coaches early in their careers have many potential untapped sources of coaching confidence. Most coaches have some experience as athletes, typically in the sport they now coach. This experience as coach watchers is a rich potential source of coaching confidence. Coaches can take a moment to think back to their favorite coaches and ask themselves questions such as the following: Why did I enjoy playing so much for this coach? What were some of the most effective or fun strategies employed by this coach? What were this coach's strongest personal characteristics or attributes? Coaches can then challenge themselves to integrate the strengths of their favorite coaches into their own coaching style. Chances are they will find that they already embody many of these strengths, which in turn will further increase their coaching efficacy. Recognizing and building on strengths also helps coaches build their mental toughness, another key component of coaching resilience. Although coaches certainly require mental toughness, rarely is this topic addressed in the coaching literature. On the other hand, much has been written about strategies for helping athletes build mental toughness:" 45 A review of that literature provides a useful foundation for creating strategies to help coaches build their own mental toughness. One model of mental toughness is referred to as the four Cs model, which includes four components of mental toughness: control, challenge, commitment, and confidence. Control is described as the ability to remain focused and disciplined while juggling multiple and sometimes competing demands. Mentally tough coaches demonstrate control by developing strong organizational skills that allow them to prioritize their many tasks and to delegate responsibilities to other members of their staff and to their athletes when possible. The most effective coaches also show control by setting aside dedicated and protected time in their daily schedules to prepare practice and competition plans. The challenge component of mental toughness refers to the ability to perceive the constant challenges and changes that occur in our lives as opportunities for development. In this sense, mentally tough coaches are growth mind-set coaches who embrace obstacles and setbacks as valuable moments for improvement. Mentally tough coaches don't shy away from adversity; they tackle it head on and display deliberate and timely decision making. Coaching is complicated, and seldom is time available to create or implement the best solution to a challenge. Mental toughness increases each time a coach acts with purpose and conviction. The third C of mental toughness, commitment, is described as the intense and constant pursuit of goals, despite difficulties that are encountered. Mentally tough coaches embrace the goal-setting philosophy of plan backward and execute forward. Mental toughness is exhibited when coaches help their athletes set realistic and challenging goals and then work diligently to help athletes incrementally close gaps between their current levels of performance and the target goal. Staying focused on long-term goals that may take years to achieve requires great coaching commitment. Confidence, the fourth and final C of the mental toughness model, is self-belief in spite of setbacks. Besides undertaking the coaching efficacy activities already suggested in this chapter, coaches can build the confidence part of their mental toughness by practicing mental skills such as imagery and positive self-talk. For example, coaches can imagine themselves leading an efficient and productive practice session or coaching with composure and integrity during tough competition situations. Several mental toughness questionnaires have been created for use with athletes, including the Mental Toughness Scale (MTS). A simplified version of the Mental Toughness Scale adapted for coaches to self-assess their mental toughness is provided in figure 11.5. Questions on which the coach scores high (4 or 5) should be recognized as a mental toughness strength for the coach. Questions on which the coach scores low (1 or 2) present opportunities for improving the coach's mental toughness.

|