| Baserunning – Using The Decoy Position |

| By: Mike Roberts

Originally Published in: Baserunning Provided by: Human Kinetics

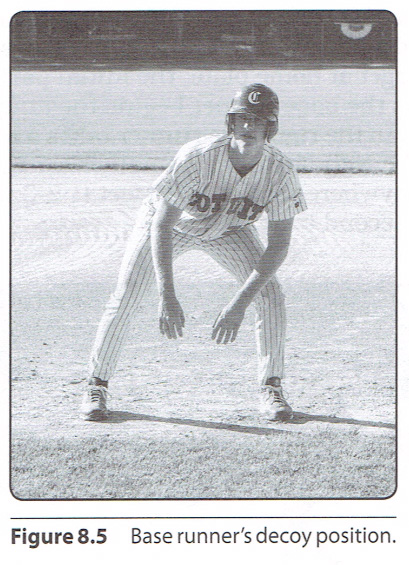

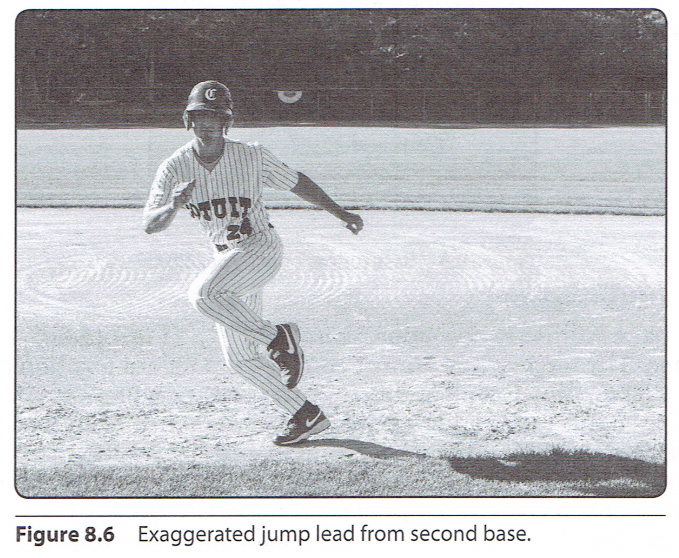

The base runner is now approximately 18 to 21 feet (5.5-6.4 m) off the base. The pitcher has almost completed a signal position on the mound. The runner anticipates that the pitcher will move after the signal is completed, and the base runner switches from a comfortable athletic position in the base line to a decoy position. As the pitcher's head moves in one of the three patterns discussed earlier to look at the runner at second base, the runner has already anticipated and beaten the pitcher's head turn to make sure he is in the decoy position when the pitcher's eyes first view the runner. The runner shifts his weight to the left side or takes a 4- to 6-inch (10.2-15.2 cm) jab step back toward second base with the left foot. The runner loses a small amount of ground but nothing significant enough to take away the steal of third. Right after the runner's weight shifts to the left, which fires up the left leg and especially the left glute, the runner springs back toward the right side. There is no hesitation in the mind or body, no sitting on the left side, just a rhythmic movement as the weight starts in the center, moves to the left, and then immediately moves back to the right side. The pitcher may still be looking at the base runner as the runner begins the slightest movement back toward the right side. This timing is ideal for the base runner. If the base runner waits until the pitcher's head and eyes are rotating back past third base and picking up the target at home plate, the initial part of the jump lead will be too late. As the base runner begins the jump in an elongated shuffle movement to the right, the runner takes a short jab step with and springs off the right foot into a small or exaggerated jump lead (see figure 8.6) anywhere from 4 to 10 feet (1.2-3 m) to as far as 30 feet (9.1 m) from second base.

Many base stealers are uncomfortable with a lead of close to 30 feet (9.1 m). This is understandable. In this case, until the athlete becomes more comfortable with the jump lead, he should shorten his primary or comfort zone lead to about 15 feet (4.6 m). This distance can still work for a base stealer but leaves little margin for error in perfectly hitting the first steps of the sprint when the pitcher's leg is just coming up to throw home with the pitch. Players can practice the jump lead almost anywhere they have 10 to 20 feet (3-6.1 m) of safe space. Set up two parallel lines approximately 10 to 12 feet (3-3.7 m) apart. In the drill, the runner tries to make a rhythmic leap from one line to the other. When leaping to the right, the runner takes a short jab step with his right foot and leaps with his left knee moving up in the air as it crosses over the right leg. The feet should land in the vicinity of the imaginary line 10 to 12 feet away, with the body still parallel to the first-base line, if the drill is performed between second and third base on a baseball field. Next, the athlete immediately takes a short jab step with the left foot and takes the right knee up in the air as it crosses over the left leg and the athlete lands back near the line he just left. The athlete should practice leaping back and forth several times. During my years of teaching and watching this drill, 1 have found that few athletes are able to use their right and left feet equally well in sync, at least at first. Every athlete has a dominant foot, but few seem to know which foot it is until beginning the drill. The leaping drill to the right and left is designed to help each foot work equally well and give runners explosiveness in the legs when the glute is fired for the leap. |